Buried History: Chicago’s Forgotten Cable Cars

Daniel Hautzinger

January 30, 2017

Race Underground: American Experience, about the challenges facing the construction of America's first subway, can be streamed for free here. Read about another facet of buried transit history in Chicago here.

Dig under the streets of Chicago and you might find traces of a forgotten past. Buried beneath modern roads are the remnants of a long-lost cable car system, “the largest and most important cable car system ever in the United States, possibly the world.” That’s according to Greg Borzo, whose book Chicago Cable Cars chronicles the short twenty-four years that cable cars provided transit to Chicagoans.

The first cable car in Chicago ran past expectant throngs on State Street at 2:30 pm on January 28, 1882- “the most important date in the history of the cable car,” Borzo claims. The last arrived at a powerhouse at 21st Street on October 21, 1906, lucky to avoid the mobs that had ripped apart the cars of the final cable trains to travel Madison and State Streets that summer.

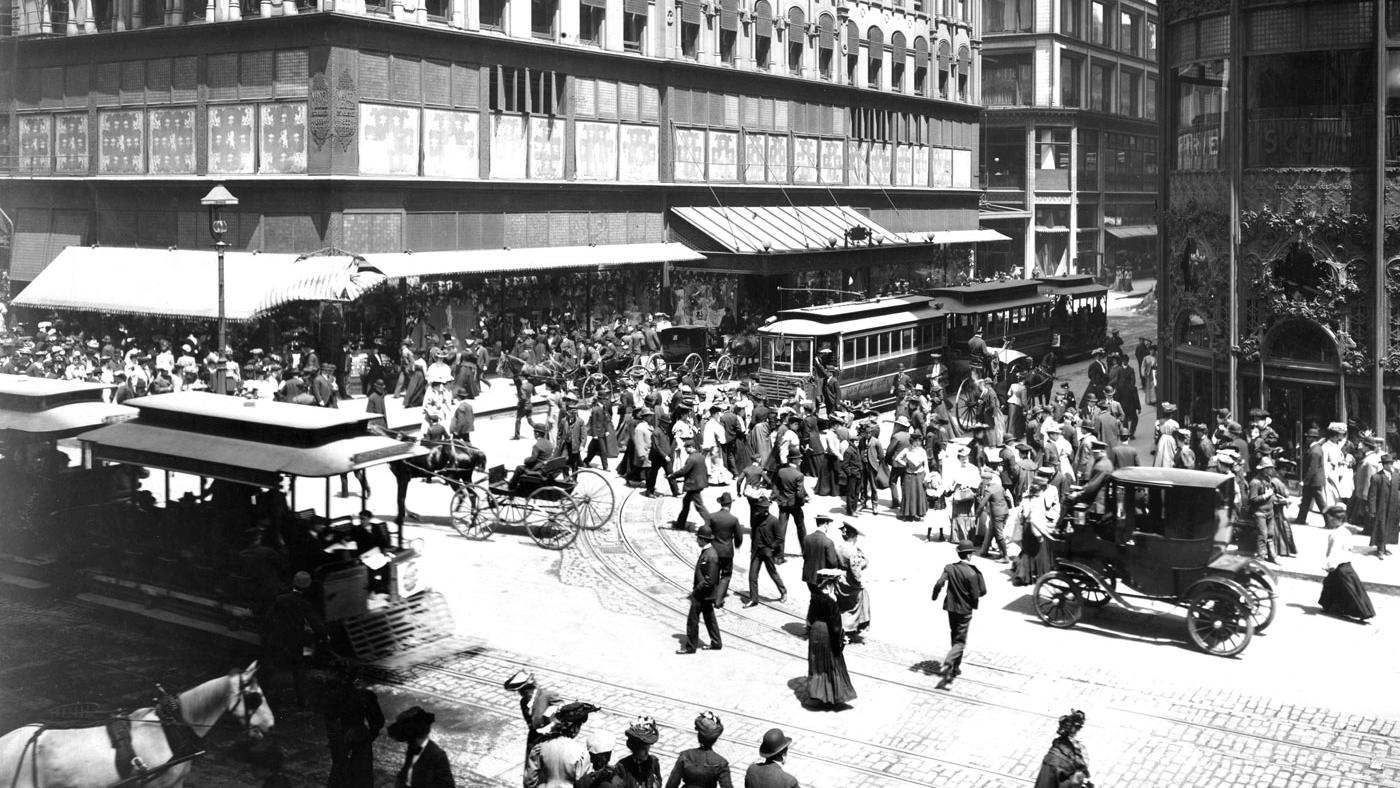

Chicago had the largest cable car system in the country in terms of ridership and actual cars. (Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum)Although few people know about it, the brief reign of cable cars in Chicago was both locally and nationally significant. In Chicago, it enabled the expansion of the city and helped tie outlying areas to the downtown as well as laying the groundwork for later transit systems. Across the country, Chicago had the most cable car passengers of any city (over one billion fares were collected here), boasted the most actual cable cars, and propelled the technology to national prominence, so that 29 cities eventually built systems.

Chicago had the largest cable car system in the country in terms of ridership and actual cars. (Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum)Although few people know about it, the brief reign of cable cars in Chicago was both locally and nationally significant. In Chicago, it enabled the expansion of the city and helped tie outlying areas to the downtown as well as laying the groundwork for later transit systems. Across the country, Chicago had the most cable car passengers of any city (over one billion fares were collected here), boasted the most actual cable cars, and propelled the technology to national prominence, so that 29 cities eventually built systems.

Before Chicago constructed its lines, the only other cable cars in the country were in San Francisco. An experimental elevated line had run for several years in New York City in the late 1860s, but it closed due to mechanical and financial problems in 1870. In 1873, a demonstration line was built in San Francisco, and over the next nine years four more short lines were built there. But until Chicago adopted the new form of transit, “the cable car was viewed as an expensive but novel way to climb steep hills,” Borzo writes.

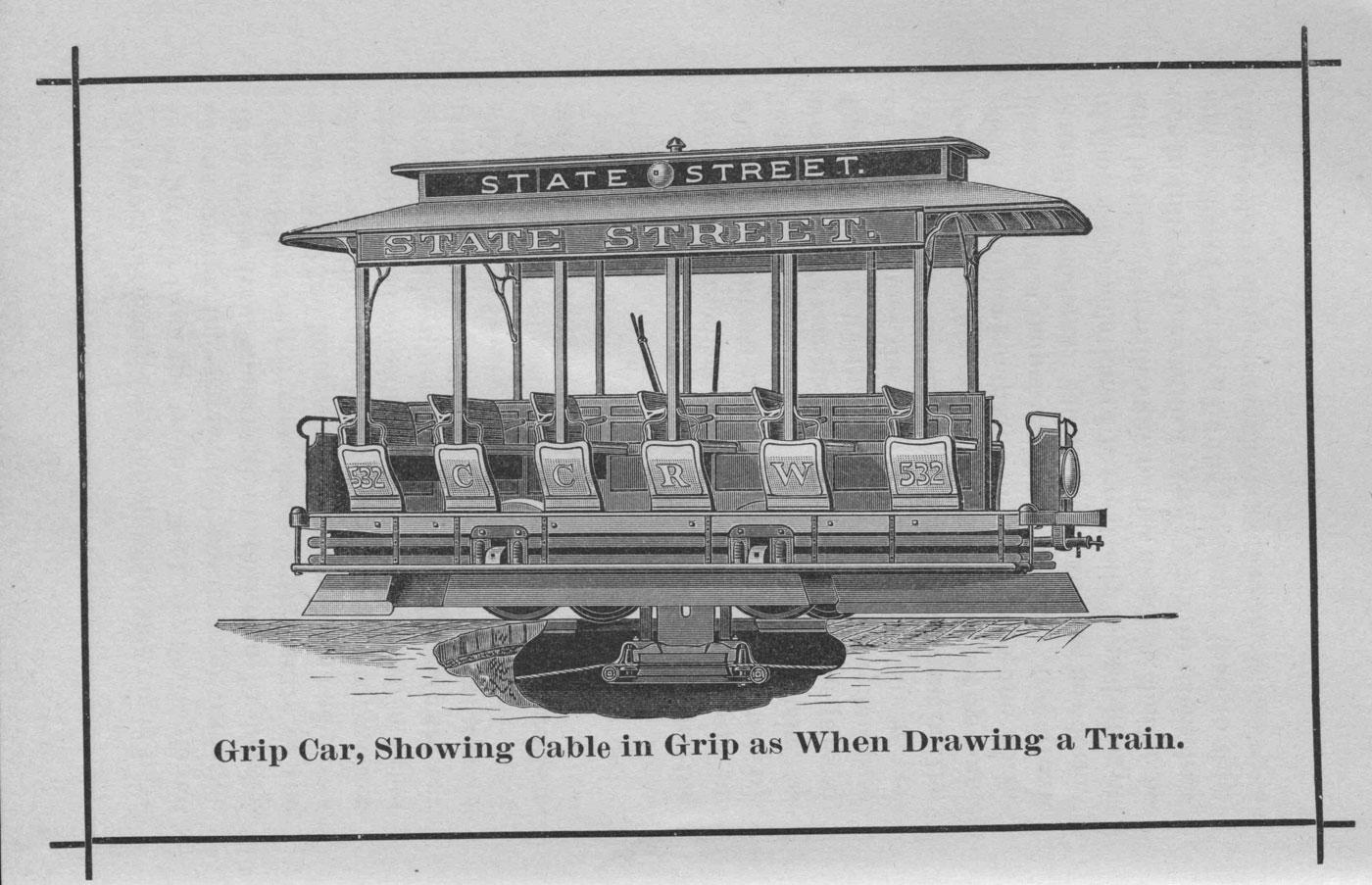

Cable cars moved by gripping a continuously moving cable buried beneath the street. (Courtesy of David Clark)Cable cars were installed in Chicago to replace horsecars, which were vehicles pulled by horses along railways in the street. Because of the rails, horsecars gave a smoother ride than a horse-drawn omnibus or carriage, but they only traveled at about 5 miles an hour, barely faster than a person could walk. Workhorses that pulled the heavy cars were cruelly overworked and abused. Cable cars provided a faster alternative to horsecars that didn’t require the use of animals. They even served as snow plows, since they were able to move through most snow, pushing it to the side.

Cable cars moved by gripping a continuously moving cable buried beneath the street. (Courtesy of David Clark)Cable cars were installed in Chicago to replace horsecars, which were vehicles pulled by horses along railways in the street. Because of the rails, horsecars gave a smoother ride than a horse-drawn omnibus or carriage, but they only traveled at about 5 miles an hour, barely faster than a person could walk. Workhorses that pulled the heavy cars were cruelly overworked and abused. Cable cars provided a faster alternative to horsecars that didn’t require the use of animals. They even served as snow plows, since they were able to move through most snow, pushing it to the side.

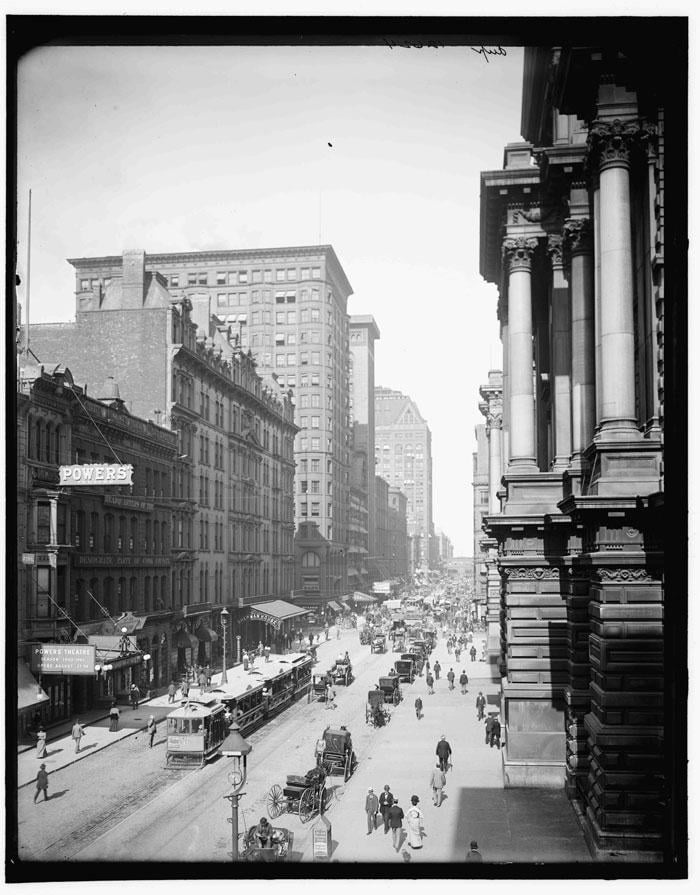

A cable car on Randolph Street. Cable cars used loops of track downtown to turn around, helping to originate the name the "Loop." (Library of Congress)The cars run by gripping a continuously moving cable buried in the street that pulls the car forward. To stop, the grip is simply released and brakes are applied. A gripman operates the car by pulling a lever that clamped the grip onto the cable, and had to pull with the force of about 125 pounds in order to suddenly stop a car. Turns and crossings could be accomplished by the release of the cable and a re-grabbing once the car had coasted around a curve or crossed an intersecting line. The gripman navigated this system by interpreting the subtle movement of the grip mechanism as it passed by pulleys and bars in the cable conduit under the street.

A cable car on Randolph Street. Cable cars used loops of track downtown to turn around, helping to originate the name the "Loop." (Library of Congress)The cars run by gripping a continuously moving cable buried in the street that pulls the car forward. To stop, the grip is simply released and brakes are applied. A gripman operates the car by pulling a lever that clamped the grip onto the cable, and had to pull with the force of about 125 pounds in order to suddenly stop a car. Turns and crossings could be accomplished by the release of the cable and a re-grabbing once the car had coasted around a curve or crossed an intersecting line. The gripman navigated this system by interpreting the subtle movement of the grip mechanism as it passed by pulleys and bars in the cable conduit under the street.

The success of Chicago’s cable cars demonstrated to the rest of the country that this was a viable form of transit for flat cities as well as for regions that experienced winter conditions. At its peak, Chicago’s system consisted of 41.2 miles of double-track rails, with thirteen powerhouses pulling 34 individual cables. Lines ran as far south as 71st Street, as far west as Pulaski, and north almost to Diversey (northbound lines ran under the Chicago River through a tunnel at LaSalle Street), allowing people to live further and further away from downtown. Instead of using turntables to send cars back in the opposite direction on a line, loops of track were built around several city blocks; this probably contributed to the later naming of downtown as the “Loop.”

But within a few years of the installation of the cable car lines, the technology was obsolete. By 1890, transit companies were switching to electric trolley lines, which were cheaper to build, operate, and maintain. Electric streetcars then continued to operate in Chicago until 1958.

An unearthed cable car sheave on Clark Street in December 2016. (Courtesy of Christine Rosenberg)While there are few visible remnants of Chicago’s cable cars, a cable-pulling powerhouse from 1887 still stands at LaSalle and Illinois Streets. Having served at various points as a car repair shop and Michael Jordan’s Steakhouse, among other things, the building has undergone modifications but is now designated a Chicago Landmark. Since removing underground cable infrastructure was labor-intensive and expensive, some of it still exists and occasionally surfaces during street renovation projects. The Museum of Science and Industry and the Illinois Railway Museum in Union, Illinois, both contain replicas of cable cars, the only two Chicago cable cars you can visit today. (After the demise of the system, some cars found an afterlife for a while as office space.)

An unearthed cable car sheave on Clark Street in December 2016. (Courtesy of Christine Rosenberg)While there are few visible remnants of Chicago’s cable cars, a cable-pulling powerhouse from 1887 still stands at LaSalle and Illinois Streets. Having served at various points as a car repair shop and Michael Jordan’s Steakhouse, among other things, the building has undergone modifications but is now designated a Chicago Landmark. Since removing underground cable infrastructure was labor-intensive and expensive, some of it still exists and occasionally surfaces during street renovation projects. The Museum of Science and Industry and the Illinois Railway Museum in Union, Illinois, both contain replicas of cable cars, the only two Chicago cable cars you can visit today. (After the demise of the system, some cars found an afterlife for a while as office space.)

San Francisco is now the only U.S. city to operate cable cars, though Seattle kept its system until 1940. But cable cars left an important legacy, especially in Chicago. From establishing routes and laying the groundwork for later forms of transit (some of the companies and investors also helped build the “L” train lines), to allowing the city to expand from beyond the downtown, cable cars are a vital, if virtually unknown, part of Chicago’s history.