The American Mythology of the Black Sox Scandal

Daniel Hautzinger

September 26, 2019

The myth of the Black Sox is a thoroughly American tall tale. It goes like this: a group of hardscrabble, outsider ballplayers who had made the Chicago White Sox one of the best teams in baseball were underpaid and underappreciated by Charles Comiskey, their miserly team owner. Comiskey’s mistreatment of his players included underhanded tactics, as when he promised the star pitcher Eddie Cicotte a massive bonus if he won 30 games, then benched him after he won 29.

So when an offer appeared to make money worth their talent by throwing their World Series games against the Cincinnati Reds, the abused players took it. Having taken the deal, they were forced to adhere to it by enforcers. When the scandal was revealed, eight players were punished so as to take away the thing they loved best: they were banned for life from major league baseball. Their reputations and careers were ruined, while baseball lost one of the best players the game had ever seen in Shoeless Joe Jackson, who was barely a part of the scandal.

“It’s a very compelling story: the myth of the underpaid Black Sox players, resentful of their owner,” says Jacob Pomrenke, the director of editorial content for the Society for American Baseball Research and editor of the book, Scandal on the South Side: the 1919 Chicago White Sox. “That is a myth that is very easy for people to believe.”

It’s not true.

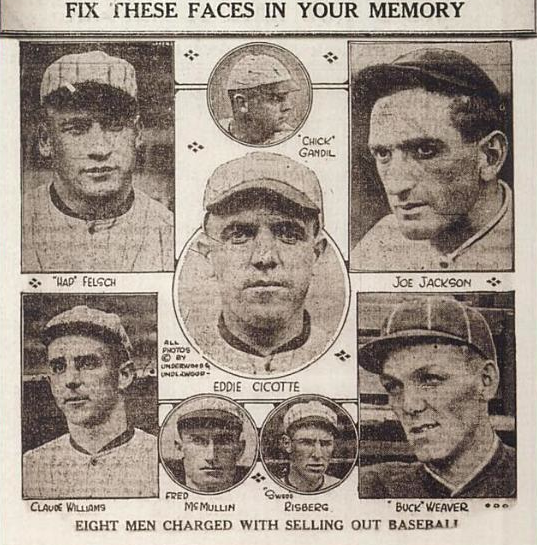

An illustration showing the eight Black Sox players banned from major league baseball for life in the October 7, 1920 edition of 'The Sporting News.' Image: Wikimedia CommonsFirst off, as Pomrenke and his colleagues have shown in their “Eight Myths Out” project, the 1919 White Sox were actually among the highest-paid players in baseball, as befits a team that won the 1917 World Series. There is no evidence that Comiskey offered Cicotte a bonus and then prevented him from winning it; Cicotte had a chance to win a thirtieth game but was pulled for pitching poorly.

An illustration showing the eight Black Sox players banned from major league baseball for life in the October 7, 1920 edition of 'The Sporting News.' Image: Wikimedia CommonsFirst off, as Pomrenke and his colleagues have shown in their “Eight Myths Out” project, the 1919 White Sox were actually among the highest-paid players in baseball, as befits a team that won the 1917 World Series. There is no evidence that Comiskey offered Cicotte a bonus and then prevented him from winning it; Cicotte had a chance to win a thirtieth game but was pulled for pitching poorly.

Cicotte was a prime instigator of the scandal, along with first baseman Chick Gandil. Enticed by rumors that some Chicago Cubs had received large payoffs for throwing the 1918 World Series, according to testimony by Cicotte, he, Gandil, and several other players approached gamblers about fixing the 1919 Series. As far as is known, no one ever threatened the players, despite a scene in both the book and movie Eight Men Out in which pitcher Lefty Williams faces a hitman. The book’s author, Eliot Asinof, admitted to making the hitman up.

Finally – and this may be the most difficult thing for many people to take – Shoeless Joe Jackson, no matter how great a player, is at least partially guilty. “Shoeless Joe Jackson took the money, there’s no doubt about that,” says Pomrenke. “He accepted a $5,000 bribe from gamblers. Did he attend any meetings setting up the fix? Not that we know of. Did he play less than his best on the field? That’s something that will be debated for the next hundred years. But there’s no question that he was involved in some way.”

Jackson, whose career batting average is the third-highest in the history of baseball, has been portrayed as a “redemptive hero” despite his guilt, says Bill Savage, a Northwestern University English professor who has taught courses on baseball and the Black Sox. “The guy was a slam-dunk Hall of Famer. There’s no doubt that he would be venerated as one of the all-time greats had the scandal not take place. Therefore he’s the guy who lost the most.” (Third baseman Buck Weaver may have had the most inordinate punishment, given that he didn't take any money and played his best during the Series; he was banned for attending two of the meetings about the fix.)

According to Savage, the revision of the Black Sox myth began with Nelson Algren in the 1950s. Before then, “the players were the villains, and organized baseball and especially Charles Comiskey were the victims,” he says, a portrayal that fed on anti-Semitic stereotypes of greedy Jewish gamblers leading the ballplayers astray. But in several pieces of writing by Algren, who had been a fan of the Black Sox team as a boy growing up on the South Side, the players are idolized in poetic language and transformed into victims. “Algren taps into the American urge to root for the underdog and the outsider,” says Savage. “It’s the power of poetry and fiction to overwhelm history.”

The White Sox at the 1917 World Series, which they won, with Shoeless Joe Jackson second from left. Photo: Bain News Service/Library of Congress

The White Sox at the 1917 World Series, which they won, with Shoeless Joe Jackson second from left. Photo: Bain News Service/Library of Congress

Jackson in particular has been portrayed as “a poor, illiterate Southerner who was taken advantage of by the big city slickers,” Savage says, and who loves baseball more than anything. The epitome of that portrayal is in the 1989 movie Field of Dreams, when Jackson and the other seven Black Sox are again afforded the chance to play baseball. “It’s this whole myth of the pure game of baseball,” says Savage. “Baseball is a business that mythologizes itself as a game. For the game to be pure, you have to play to win and you have to play for the love of it, not the money – but everybody takes the money, whether it’s a legitimate salary, the ticket sales that owners get, the concessions money, or the gamblers giving you a few bucks to blow in your direction.”

The Black Sox weren’t the only players at the time to take a few bucks. Notwithstanding its mythologizing, baseball was notably corrupt in the first decades of the twentieth century. “The Black Sox players understood that there was a low risk of getting caught and getting punished,” Pomrenke notes. “There had been other players, such as Hal Chase, the most corrupt player in baseball history, who had been caught bribing teammates and opponents, and nothing had ever really happened to them.”

White Sox owner Charles Comiskey in 1919. Comiskey learned of the scandal but swept it under the rug. Image: Wikimedia CommonsPomrenke also points to the 1919 New York Giants, who had eight players banned for life, “mostly for gambling-related offenses,” and Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker, who fixed a regular season game just a week before the Black Sox’s 1919 World Series. “Every team in baseball had players who were susceptible to bribes,” he says.

White Sox owner Charles Comiskey in 1919. Comiskey learned of the scandal but swept it under the rug. Image: Wikimedia CommonsPomrenke also points to the 1919 New York Giants, who had eight players banned for life, “mostly for gambling-related offenses,” and Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker, who fixed a regular season game just a week before the Black Sox’s 1919 World Series. “Every team in baseball had players who were susceptible to bribes,” he says.

Organized baseball was aware of the corruption, but did nothing to stop it. (For Savage, this and the subsequent erasure of the scandal is a “quintessential Chicago aspect” of it. “Chicago has a tradition of being run by boosters who want to make everything positive and who ignore, bury, neglect, cover up reality.”) Both Comiskey and American League president Ban Johnson had “guilty knowledge” of the Black Sox Scandal, Pomrenke says, but swept it under the rug until it came to light, due in part to persistent journalists. Almost a year after the 1919 World Series, Chicago Cubs leadership disclosed reports of a fixed game between the Cubs and the Phillies, leading to the empanelment of a grand jury in Cook County. Johnson, who was feuding with Comiskey, and others encouraged the grand jury to turn its attention to the 1919 World Series.

Pomrenke believes that gambling in baseball was finally addressed publicly with the Black Sox because America at large was moving into a progressive reformist era, and because the scandal involved a World Series. And organized baseball did finally move to stamp out gambling in the wake of the scandal, even though the eight Black Sox were found innocent in court. The team owners hired a federal judge, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, to become the first Commissioner of Baseball – and Landis promptly banned all eight players for life.

“The culture of the game was changed forever,” says Pomrenke. “What had always been permitted under the surface was no longer being permitted.” Not that corruption disappeared completely from baseball: look at Pete Rose, or steroids. Nor do official baseball, and especially the White Sox, seem keen to remember the Black Sox. As Savage points out, at Guaranteed Rate Field, “there’s all this celebration of the team’s history – but not a whole lot of 1919 stuff, or even 1917 stuff [when the team won the World Series with many of the Black Sox players]. On one hand, I kind of can’t blame them. But on the other hand, we have to confront history if we’re going to learn anything from it.”