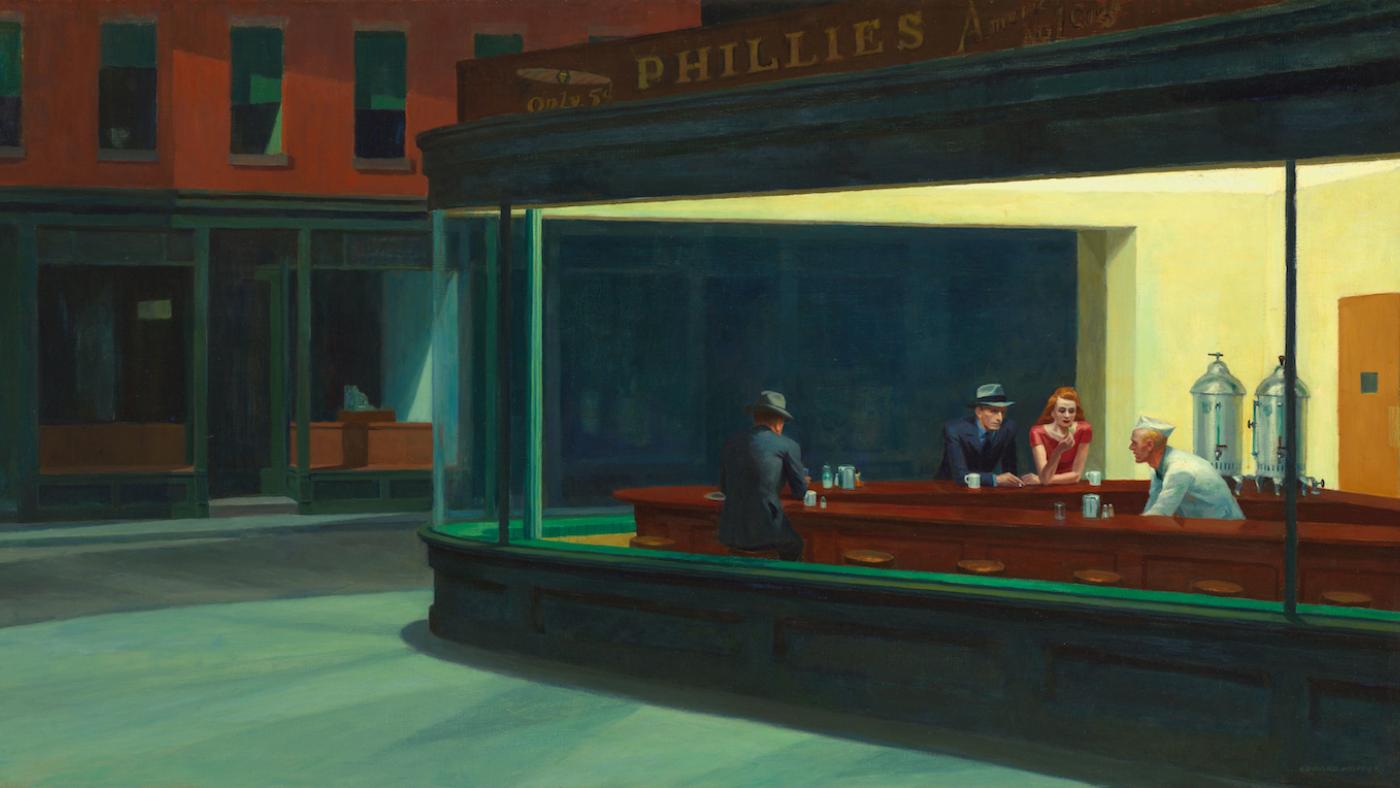

Edward Hopper's Iconic 'Nighthawks'

Daniel Hautzinger

January 2, 2024

American Masters – Hopper: An American Love Story premieres on WTTW and streaming on Tuesday, January 2 at 8:00 pm.

It’s one of the most iconic American images, endlessly parodied and referenced, and it hangs in the Art Institute of Chicago. Nighthawks by Edward Hopper depicts three customers at the bar of a garishly lit diner on an empty city corner at night. One man’s back is to the viewer; a redheaded woman in a red dress sits next to the other man. A soda jerk in a white cap and jacket bends towards something behind the counter. Two urns of coffee sit near a door that seems to lead to a kitchen; no entrance into the diner from the dark outdoors is in sight.

“It is, I believe, one of the very best things I have painted,” Hopper wrote to Daniel Catton Rich, the director of the Art Institute, after Rich bought the painting for the Art Institute in 1942, the very year that Hopper made it. “I seem to have come nearer to saying what I want to say in my work, this past winter, than I ever have before.”

What, exactly, Hopper wanted to say has always been up for debate. Many people have seen him as a bard of American solitude, depicting lone or lonely figures in gas stations, automats, homes. “We are all edward hopper paintings now,” read a March 16, 2020 tweet that came as the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered businesses and forced everyone into isolation. Joyce Carol Oates imagined in a poem that the man sitting next to the woman was having an affair with her, but that she didn’t really trust that it would stick; they sit in mutually unintelligible silence. (The Chicago author Stuart Dybek also took inspiration from the painting in a short story in his book The Coast of Chicago.) Hopper himself eventually allowed that, “unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.”

But in an interview near the end of his life, he also cast doubt on the reading of loneliness in his paintings. “Well, I think those are the words of critics,” he said. “It may be true, it may not be true. It’s how the viewer looks on the pictures, what he sees in them.”

Indeed, another reading of Nighthawks from the early days of the pandemic came from the Art Institute’s Sarah Kelly Oehler, the Field-McCormick Chair and Curator of American Art. Noting that Hopper was inspired by the darkness he encountered in walks around New York City after the attack on Pearl Harbor led to blackout drills and the dimming of both lights and spirits, Oehler surmised a comforting tone in the painting.

“Perhaps Hopper saw this brightly lit diner not as a place of disconnection but as a beacon of light and hope against the darkness, a moment of finding community when everything outside seemed grim and unbearable,” she wrote at a time when everything outside once again seemed grim and unbearable.

While Hopper was by many accounts an irascible man, he did find a deep connection with his wife and fellow painter Josephine Nivison Hopper. In one early meeting, he started to recite a work by a favorite poet, Paul Verlaine, and she picked up where he left off. She recommended him to gallerists at a time when he hadn’t sold a painting for ten years; her artistic career tapered off as she tended to his, as the new American Masters documentary Hopper: An American Love Story shows. Jo served as the model for the redhead in Nighthawks, while Hopper himself was the model for the two seated men.

But it is the everyday nature of the people and the scene, however imbued with pathos, that has so imprinted it in American culture – a sense that “any of us could be sitting in this diner,” as the former Field-McCormick Chair and Curator of American Art at the Art Institute Judith Barter says in a 2016 video. As the late critic Peter Schjeldahl put it, Hopper’s “mature art…is timeless, or perhaps time-free: a series of freeze-dried, uncannily telling moments.”