A New 'NOVA' Documentary Explores the Promises and Perils of A.I.

Daniel Hautzinger

March 27, 2024

NOVA: A.I. Revolution premieres on WTTW and streaming Wednesday, March 27 at 8:00 pm.

Artificial intelligence is associated in the general public consciousness with eerily lifelike chatbots like ChatGPT, manipulative deepfake videos, machine-made songs, and the doomsday scenario of an A.I. that grows too powerful and tries to extinguish humanity, as in The Terminator. But what about artificial limbs?

In the new NOVA documentary A.I. Revolution, the journalist Miles O’Brien tries out a robotic arm trained with A.I. to replace the limb he lost ten years ago. The Chicago company Coapt – which grew out of the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab – has developed a system that harnesses A.I. to teach a robotic arm to recognize patterns of electrical signals sent from the remains of an amputee’s limb and connect it to specific movements, thus allowing a wearer to in theory not only move the arm but flex individual fingers.

“It’s really kind of cool, and I’m gratified that I can wear this cool robot arm,” O’Brien says.

That’s just one of the many possible applications of A.I. that could revolutionize medicine. There’s the possibility to predict breast cancer before a human eye could ever spot it, or the ability to analyze and understand proteins in order to create bespoke drugs. Outside of medicine, A.I. is helping spot early signs of forest fires and being put to other beneficial uses, as O’Brien explores in A.I. Revolution, which goes beyond the most talked about types of A.I. to spotlight a few of the potentially game-changing ideas currently out there.

“The more I dove in, the more I realized this arm thing is just a simple piece of A.I. that is totally the tip of the iceberg in the world of health care, and how that really can change people’s lives,” O’Brien says.

Terminator scenarios aside, it’s hard to overlook the positive applications of A.I., he says. “That’s what I think has been a little bit lost in the concern, the Chicken Little stuff that has happened more recently.”

Not that he doesn’t worry about the implications of such an unbelievable technology. “If we talk in ten years and our robot overlords are controlling us, you could say I was a Pollyanna,” he says with a laugh. A.I. Revolution digs into negative possibilities, too, as well as the debate over how to regulate or slow the development of A.I.

“I just hope that, as this debate rages, we don’t just keep kicking the can down the road until someday the A.I. collectively will be smarter than all of us, and then what?” O’Brien says. “If we haven’t thought about this, we’re going to be in a bad way.”

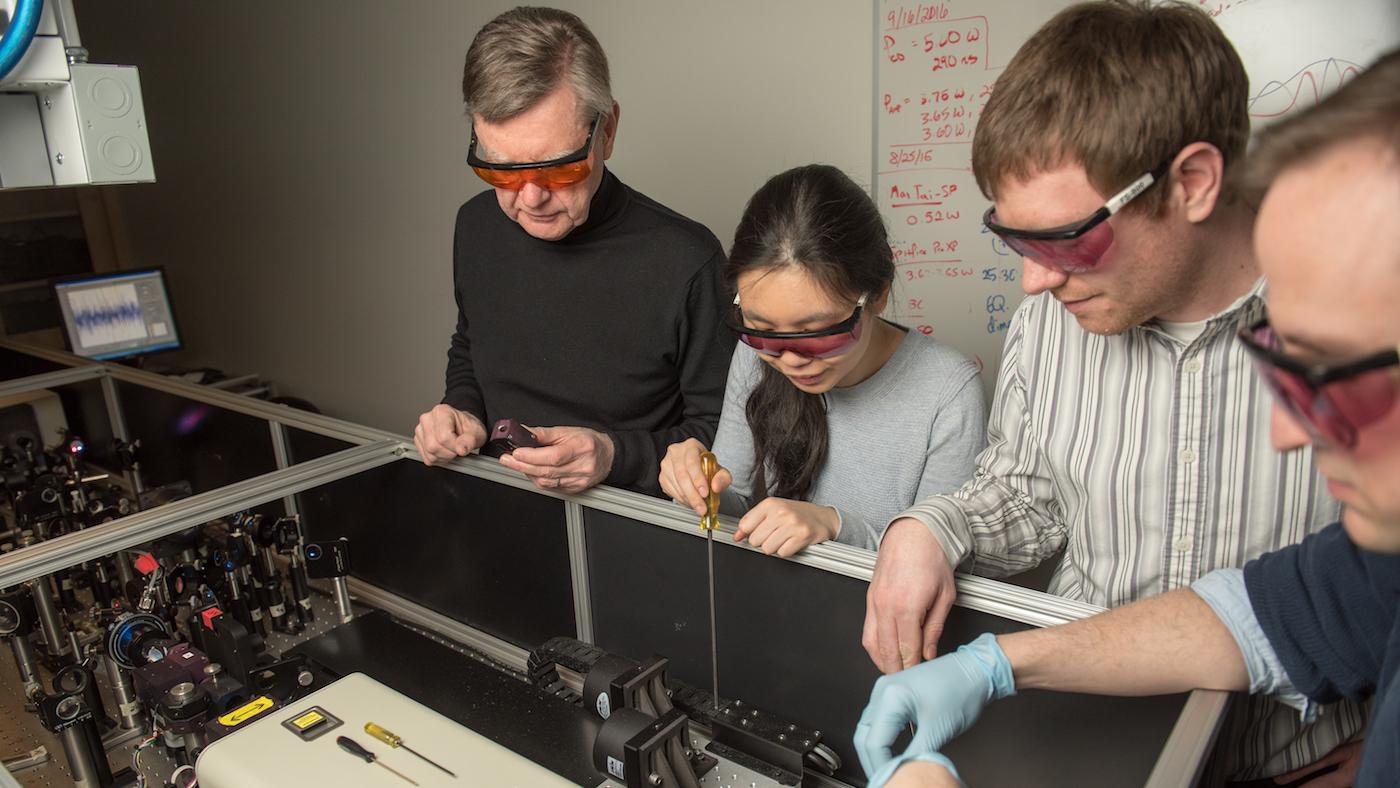

There’s a whole group of very smart people involved in technology and A.I. research who call themselves A.I. safetyists or decelerationists and go around asking what someone’s p(doom) is – the probability that A.I. will lead humanity to extinction. Among the three people known as the godfathers of A.I., two now want to slow down its development, including Yoshua Bengio, who appears in A.I. Revolution.

“You do have to listen to what people like [Bengio] say, there’s no question about it,” O’Brien says. “But I do think that he’s such a forward thinker. He’s so far ahead of us…When we listen to him, we should not discount, but we also should not think this is going to happen tomorrow.

“I do think that A.I., at the bottom of the ledger, has great potential to give us more than it might take away, if we just get ahead of this and have a conversation and be reasonable about its usage,” he says.

Nevertheless, he does harbor fears. “A pessimist is an optimist, only better informed,” he says. “I want to be that optimist so badly because I do firmly believe that we’re in this race to grapple with real existential threats, climate [change] being the top of the list, and A.I. might get us” to solutions. “But there’s this simultaneous race to do the lowest common denominator and create fake news fiction or whatever dark scenario or machines that won’t listen to us.” he continues.

“I think if we don’t develop this, we’re cooked. I think if we do develop this, we’re cooked.”

But for now, A.I. is still a tool to be used by humans, not a replacement for us. “These models are absolutely nothing without the hard work we do to put data into the system,” he says. Just look at his experience with his innovative, A.I.-trained robotic arm. While he perhaps hasn’t put in enough time yet to fully learn with it and make it as effective as possible, so far it has been only moderately useful, not much of an improvement on the mechanical arm that he usually uses.

According to him, “As far as honest-to-goodness utility goes, rubber bands and a bicycle cable are about equal.”