How Upton Sinclair’s 'The Jungle' Unintentionally Spurred Food Safety Laws

Meredith Francis

January 23, 2020

Learn more about the origins of food safety in the United States in American Experience: Poison Squad, which airs Tuesday, January 28 at 9:00 pm and is available to stream the following day.

When Upton Sinclair set out to write his 1906 novel The Jungle, he was trying to bring attention to the dismal living and working conditions for immigrants working in the meatpacking industry. Instead, his novel inspired a national movement for food safety.

Sinclair set The Jungle in the meatpacking district and stockyards of Chicago, where many immigrants settled in the hopes of making a living in America. The real-life stockyards, such as Chicago’s Union Stock Yards, inspired Sinclair’s bleak portrayal. They consisted of a square mile of livestock pens, packing plants, slaughterhouses, and railroads. At its zenith, it processed 18 million animals a year.

Being a “muckraker” journalist, Sinclair was intent on exposing the workers’ experiences with the industry and the hardship they faced outside of work. Born in 1878, Sinclair was a self-proclaimed socialist and was just 28 when The Jungle was published. It was first published serially in the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason. Though he reported and researched the novel for seven weeks by visiting the stockyards and interviewing workers, it was a work of fiction.

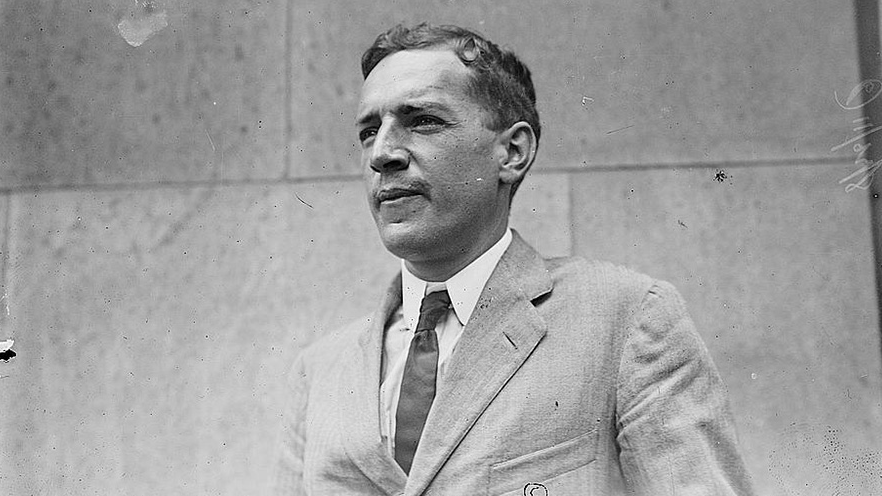

Upton Sinclair was a socialist and a muckraker journalist. Photo: Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Upton Sinclair was a socialist and a muckraker journalist. Photo: Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The novel tells the story of a Lithuanian immigrant family who endures relentless tragedies as the main character, Jurgis Rudkus, tries to support his family. Jurgis’ tragic journey leads him to loss, unemployment, imprisonment, and alcoholism.

The experiences of Jurgis would have been familiar to the real-life stockyard workers. In The Jungle, Sinclair describes them as “hanging always on the verge of starvation, and dependent for [their]opportunities of life upon the whim of men every bit as brutal and unscrupulous as the old-time slave drivers.” In his reporting, he discovered that laborers encountered oppressive heat, foul smells, and the gore that came with working in a slaughterhouse:

All day long the blazing midsummer sun beat down upon that square mile of abominations: upon tens of thousands of cattle crowded into pens whose wooden floors stank and steamed contagion; upon bare, blistering, cinder-strewn railroad tracks, and huge blocks of dingy meat factories, whose labyrinthine passages defied a breath of fresh air to penetrate them; and there were not merely rivers of hot blood, and carloads of moist flesh, and rendering vats and soap caldrons, glue factories and fertilizer tanks, that smelt like the craters of hell—there were also tons of garbage festering in the sun, and the greasy laundry of the workers hung out to dry, and dining rooms littered with food and black with flies, and toilet rooms that were open sewers.

But readers of The Jungle became more fixated on the lack of sanitary conditions in food processing facilities like the stockyards. As Sinclair famously said, “I aimed at the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”

In describing the meat-packing plants, Sinclair painted a queasy picture. He said meat often fell onto the floor amid dirt and sawdust, and was stored in giant piles in rooms with leaky roofs. Even worse? The rats.

“It was too dark in these storage places to see well, but a man could run his hand over these piles of meat and sweep off handfuls of the dried dung of rats,” Sinclair wrote. “These rats were nuisances, and the packers would put poisoned bread out for them; they would die, and then rats, bread, and meat would go into the hoppers together.”

In the decades preceding The Jungle, Congress had attempted multiple times to regulate the food industry, to no avail. But the response to Sinclair’s novel was immediate, despite some initial skepticism from the government. President Theodore Roosevelt referred to the muckraker, who wrote impassioned letters to the president with his input, as a “crackpot,” and distrusted Sinclair’s socialism.

But the government’s official investigations found that Sinclair’s portrayals of the sanitary conditions in the stockyards were true, and public outrage led to Congress enacting two laws. The Pure Food and Drug Act prohibited the sale of “misbranded or adulterated food and drugs.” Similarly, the Meat Inspection Act prohibited the sale of “misbranded or adulterated livestock” and ensured sanitary conditions for livestock slaughtering and meat processing.

Sinclair may have failed to attract the nation’s passion to overhaul the dismal working conditions in places like Chicago’s stockyards, but he did at least make immigrant workers—and everyone else’s—lives a bit safer by inspiring some of the United States’ first food safety laws.