Artist Chris Pappan Explores the Contemporary Identity of Native Americans

Meredith Francis

December 3, 2020

For Chris Pappan, an artist and enrolled member of the Kaw Nation, art is a powerful way to assert the identity of Native peoples as contemporary — and to undo offensive depictions of Native Americans found in everything from movies to mascots.

“We call ourselves Kanza, which is where the word Kansas comes from,” Pappan said of his Kaw heritage. “Originally, our people are from Kansas, but I didn't grow up in Kansas or on the current reservation, which is in Oklahoma. I grew up in Flagstaff, Arizona. So I consider myself totally displaced.”

Chris Pappan is a full-time artist working in Chicago. Photo: Courtsey of Tran Tran

Chris Pappan is a full-time artist working in Chicago. Photo: Courtsey of Tran Tran

According to his website, he also has Osage, Cheyenne River Sioux, and mixed European heritage. As a child, Pappan said he was “always, always drawing and painting” and got recognized for his talent in grade school. After high school, he studied at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. There, he met his wife, Debra Yepa-Pappan, who grew up in Chicago. After graduating, Pappan moved with her to Chicago.

His work has been in exhibitions all over the world, including England, Australia, Switzerland, Kansas, Washington, D.C., and in Chicago, at the Field Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art in its The Long Dream exhibition, which is scheduled to be up through January 27, 2021 and is available to view digitally. Pappan, who is a full-time artist, also recently contributed artwork to the Google Doodle about the famed Osage ballerina Maria Tallchief.

One of the goals of his work is to reveal and dismantle incorrect or offensive depictions of Native American history and culture.

“Thinking about people's education of Native American history in this country is very one-sided, very minimal, very distorted,” Pappan said. “People get Native identity through a sports mascot, or certain portrayals in movies or on TV, which is all completely distorted.”

Some of his art incorporates a style of art known as “lowbrow.” The lowbrow movement, sometimes called pop surrealism, emerged in the 1960s and ’70s in Los Angeles. According to one blog, punk, psychedelic rock, cartoons, and street art all influence the style. In Pappan’s words, lowbrow art is “a genre of work where the technical ability is very precise, very illustrative, sometimes photorealistic, sometimes surrealistic. The subject matter is often lurid or lascivious.”

Though Pappan doesn’t always think of his art as lowbrow, it’s where he got his start.

“I was seeing some non-Native American artists appropriating Native American imagery in their lowbrow artwork,” he said. “I wanted to challenge that and say, what if I was a Native artist doing lowbrow artwork and put that into Native American art history context and see where that would take me?”

One way Pappan does that is by merging the low-brow look with ledger art, which emerged in the mid-1800s as Native Americans were being forced west off their land. Using ledger paper from the books of soldiers and merchants, Native Americans drew narrative and pictographic images that were previously drawn on items like teepees, clothing, and shields.

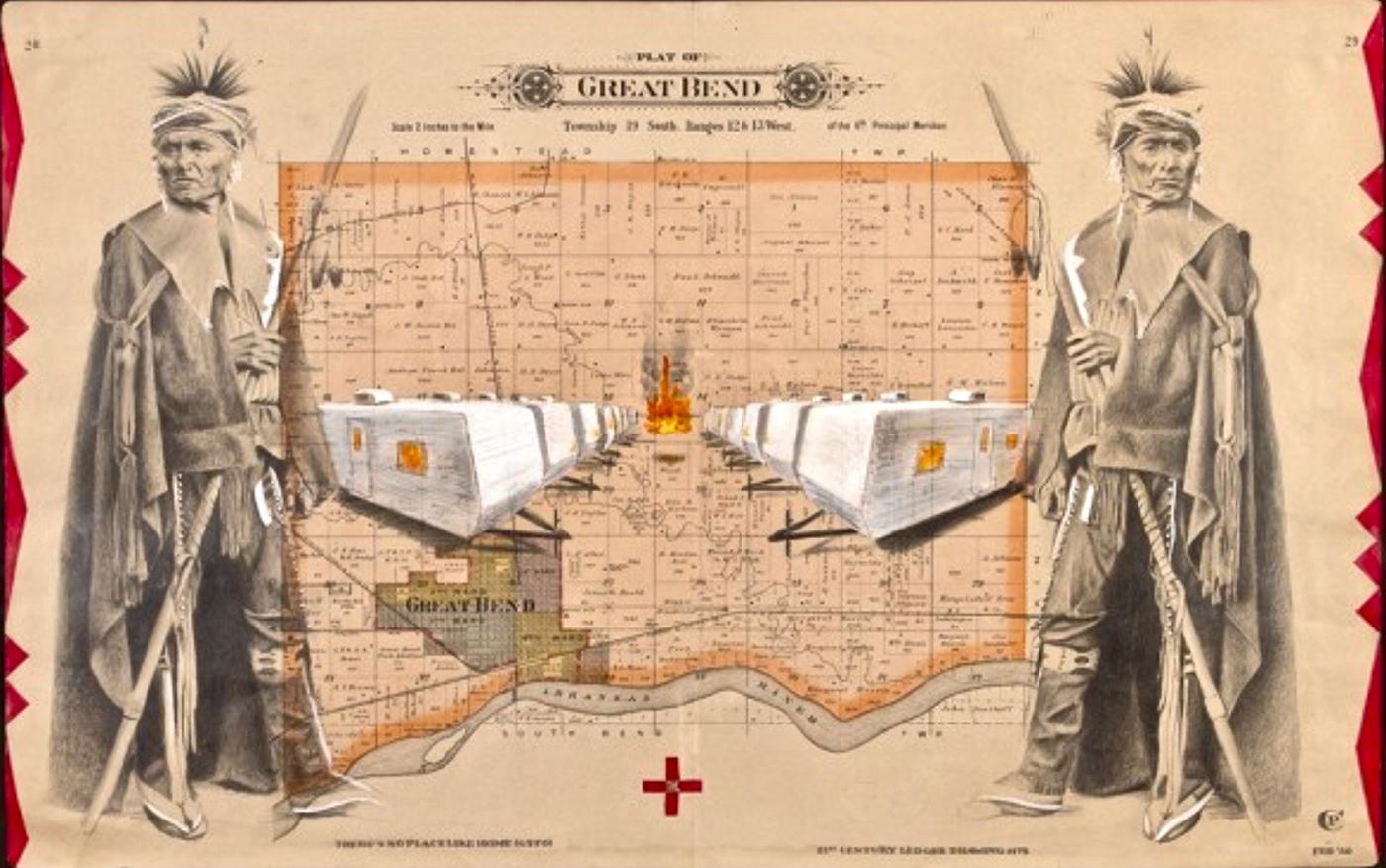

"There’s No Place Like Home," by Chris Pappan. Mixed media on vintage map. 2020.

"There’s No Place Like Home," by Chris Pappan. Mixed media on vintage map. 2020.

Pappan said he likes to blend the lowbrow aesthetic with the tradition of ledger art to “assert the identity” of indigenous peoples as modern, rather than people consigned to history.

“Through the denial of our history and through our erasure, we’re not seen as contemporary people,” Pappan said. “I wanted to fuse [ledger art and lowbrow art] to help the tradition of ledger art move forward into today and onto the future.”

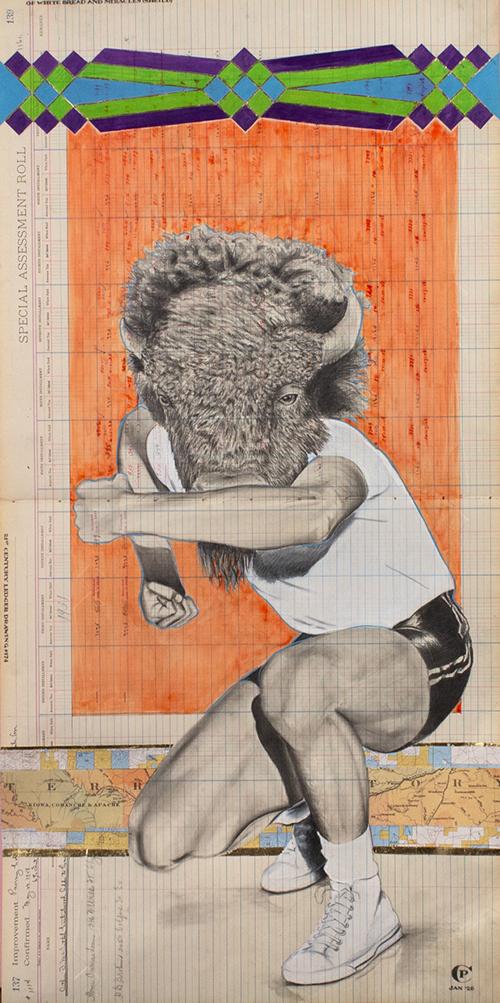

In one recent series titled Of White Bread and Miracles, Pappan wanted to tackle an issue “we have to deal with as Native people all the time” — the appropriation of images or traditions that erase the original meaning or intent. Pappan said he stumbled upon a Boy Scout manual from the 1960s, and the manual contained images that were supposed to teach children how to dance as if they were in a Native American pow wow.

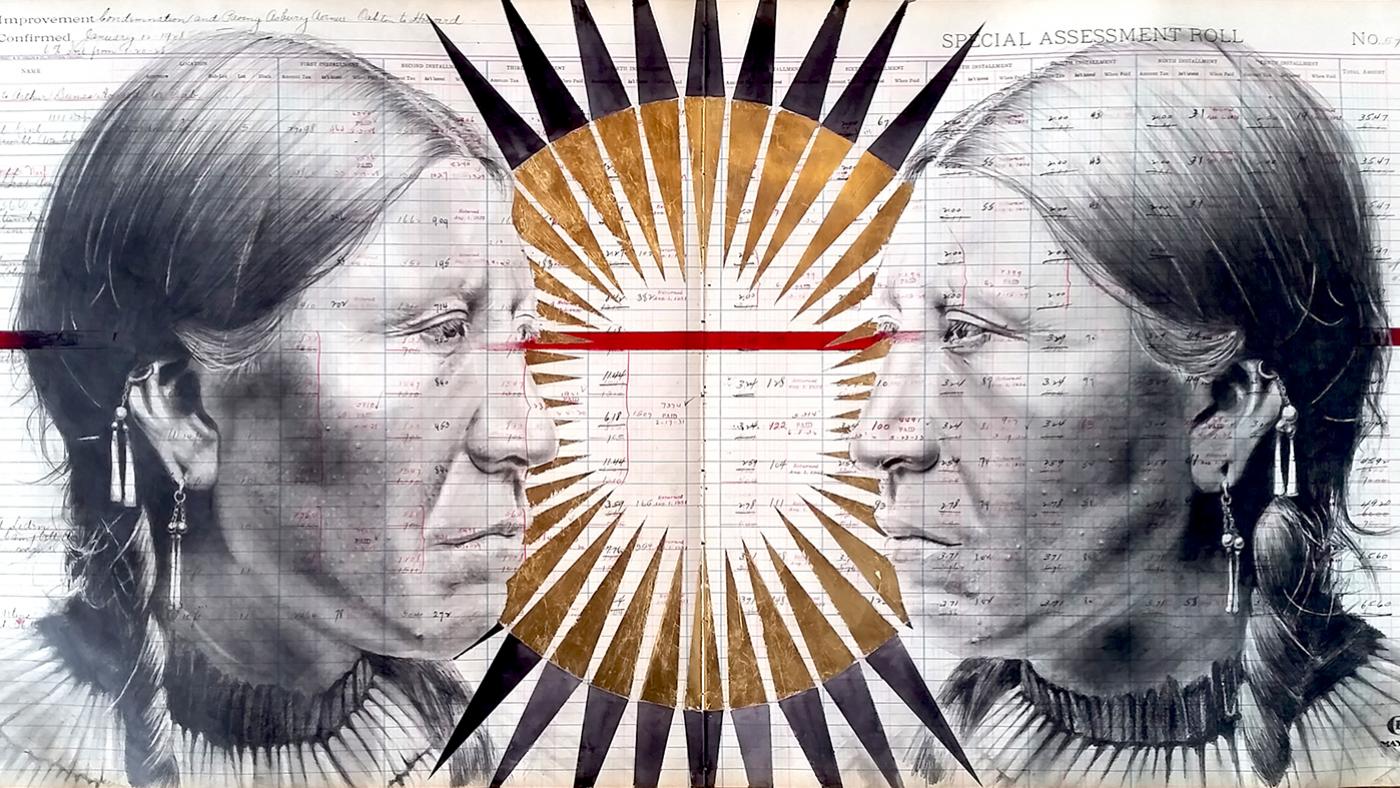

"Of White Bread and Miracles (Shield)," by Chris Pappan. Mixed media on Evanston municipal ledger. 2020.

"Of White Bread and Miracles (Shield)," by Chris Pappan. Mixed media on Evanston municipal ledger. 2020.

The images inspired a range of emotions, including anger and disgust. For Native people all across the country, dance is a spiritual act and a prayer, said Pappan, whose daughter dances.

“It’s already problematic, but then the idea of trying to teach these kids dance through these awkward, static, black-and-white photographs — it just doesn’t make any sense,” Pappan said.

He took the images of the “dance instructors” from that manual and repurposed them to look like Native American spiritual figures in order to show that dance has a higher purpose in this context. He also added colors and shapes to provide a sense of movement in the images, since in the Boy Scout manual illustrations, “you can’t tell what they’re doing.”

“The whole idea was to bring the spirituality back to these things, to undo the erasure,” he said.

For Pappan, his career as an artist has been one of discovery.

“I was displaced. I didn’t grow up with my culture. I did grow up next to the Navajo reservation, so that was my experience with it growing up, but I know that wasn’t me. That wasn’t my culture. Mine was different from theirs.”

It took Pappan years to understand that he had grown up disconnected from his own culture — and his artwork has been there to aid in the learning process.

“I think [art is] important for others that are or have been in my position. They can still learn about themselves, no matter how old they are,” Pappan said. “There’s power in art. It has this power that will take you places and help you learn about yourself.”