A Q&A with the Producers of a New Documentary about the Reversal of the Chicago River

Julia Maish

September 14, 2023

Chicago Stories: The Race to Reverse the River premieres on Friday, September 29 at 8:00 pm on WTTW and wttw.com/chicagostories.

From the time of Chicago’s founding in 1833, residents and businesses alike dealt with waste by dumping it directly into the Chicago River, which flowed into Lake Michigan—the source of the city’s drinking water. In response to the major public health crisis that resulted, officials devised a bold solution—to reverse the flow of the Chicago River. Chicago Stories: The Race to Reverse the River, which premieres Friday, September 29 at 8:00 pm as part of the new season of WTTW’s Chicago Stories documentary series, tells the story of this astonishing feat of engineering, the controversies that resulted, and the repercussions still being felt today. This month, we sat down with writer/producer Eddie Griffin and executive producer Anna Chadwick Gardner to learn more about the story and its significance to us today.

This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

Why do you think this is a quintessentially Chicago story, and why is it important to tell now?

Eddie Griffin: Without the river’s reversal, who knows what would have become of the city? Diseases like typhoid and cholera do not discriminate, so this was a matter of life and death for all Chicagoans. I love this story, because when faced with an impossible task, city leaders just figured out how to get it done.

Anna Chadwick Gardner: This is a classic Chicago story in that Chicagoans came up with big, bold solutions to big problems. It’s a fascinating story of desperation and determination.

This is a familiar story to many. What will we learn that is new?

Griffin: While it might be common knowledge that the Chicago River was reversed, most people don’t know how it was reversed. Once you know the full story, you will never look at the river in the same way.

Gardner: It’s a story full of feats of engineering, colorful characters, controversy, and drama. And it’s still relevant today, as officials grapple to protect our water supply as the climate crisis leads to more flooding events.

We meet some key historical figures in the documentary. Who were they, and how were they involved in the plan to reverse the river?

Griffin: Thousands of planners, workers, and supervisors, over almost a decade, had a hand in reversing the river. It was a self-taught engineer named Ellis Chesbrough who made the plan a reality, but even he died before the project started. So this story really personifies the entire city of Chicago as the “hero.” It was too big of a problem for any one person—it took a collective of bold thinkers to solve it.

Before engineers arrived at the reversal plan, what were some of the earlier attempts to improve sanitation, and why did they fail?

Griffin: This was not the first time the city had attempted to reverse the river. They tried it back in the 1870s and it worked for a very short time. They used water pumps to run the river water backwards into the Illinois & Michigan Canal, but the waterway was just too narrow, and heavy rains would undo the reversed flow. They were on the right track; they just needed to dig a bigger canal.

Gardner: Chicago was built on low-lying marshland, so wastewater had nowhere to drain. Chesbrough came up with a bold plan: to raise the entire city out of the muck and build a new sewer system on top of the streets. Using an elaborate system of jacks, city buildings were hoisted up to 10 feet, and new streets were built above the sewers. This worked, but the waste still ended up flowing back in the river. So Chesbrough came back with another wild idea: to build a two-mile tunnel underneath Lake Michigan. His plan was to pull cleaner water from an intake crib a mile offshore. And for a time it worked, until the sewage made its way out to the intake. Ultimately, Chesbrough’s most audacious proposal had to be implemented: reversing the Chicago River.

Once the reversal project was underway, what were some of the major challenges the workers faced in making it a success?

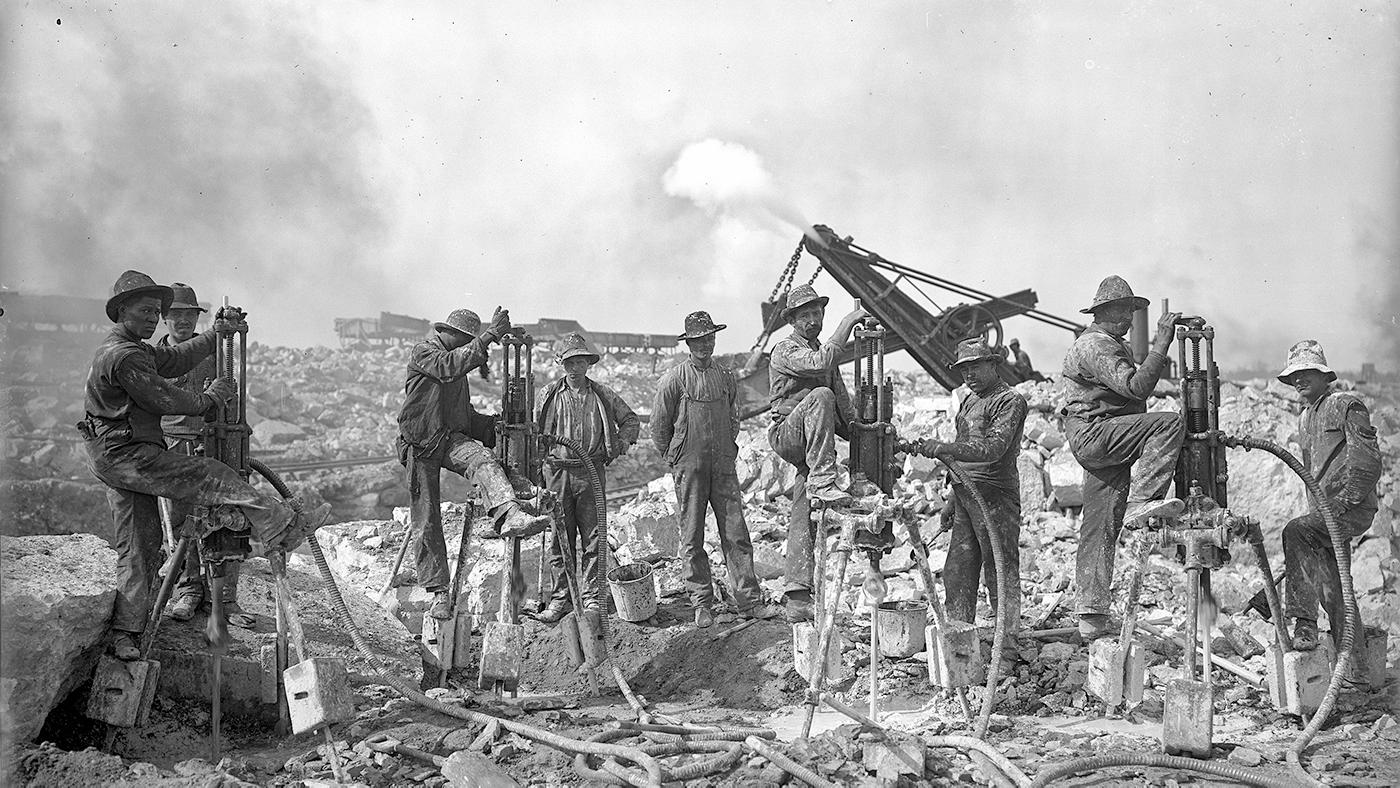

Griffin: The reversal was an incredibly dangerous project, involving digging and dynamiting through 30 miles of earth and rock. 275 people died digging the canal. But everyone understood the risks and knew how vital it was to get this job completed. There was no turning back.

Gardner: This was dirty, backbreaking work. The canal workers—mostly Eastern European immigrants and African Americans—had no protections. Yet they toiled for eight long years in deplorable conditions, and got the job done.

The reversal of the river solved one problem, but created others. What were they?

Griffin: The reversal caused floods downstream of Chicago, and many Illinois farmers were left with flooded fields and ruined crops that compromised their livelihoods. And the polluted water devastated entire ecosystems forever.

One of the interviewees suggests that we think of the reversal of the river not as a marvel but as a failure. Why?

Gardner: Well, it saved lives by allowing Chicago to draw cleaner drinking water from Lake Michigan. That’s an undeniable success. But some believe that reversing the river violated the laws of nature and should never have been done. Yes, it saved the city, but it caused new problems like the migration of invasive species, including the Asian Carp, into the river. So some environmentalists are advocating for restoring the river to its natural course.

What do you want the audience to take away after watching this film?

Griffin: That when city leaders realized the situation was critical, they came together to get it done. But also that we can, and should, evaluate the consequences of the reversal along with the problems it solved.

Gardner: Today, Chicagoans can dine at restaurants as boats sail by, stroll along the riverwalk, or even paddle down the river. This is all possible because of the bold action and vision of our predecessors, who defied the odds to pull off a marvel of human engineering in the name of public health.