“These Things Are Works of Art”: Chicago’s History as the Manufacturing Center for Pinball Machines

Meredith Francis

January 26, 2024

Chicago’s location at the center of the country has long made it a convenient hub for manufacturing and transportation. The city has been a leader in candy production, meatpacking, and – in perhaps an unexpected but delightful twist – pinball.

“I equate it to, Detroit for automobiles is pinball for Chicago,” says Zachary Sharpe, director of marketing for Stern Pinball. “Chicago is just like a perfect epicenter of where manufacturing can take place.”

He would know. In addition to working for a company that calls itself the largest and oldest pinball manufacturer in the world, Sharpe comes from a major pinball family and is a highly decorated, competitive player. His brother is also a competitive player who works in the industry, and his father, Roger Sharpe, was a professional pinball player, writer, and game designer. Roger was famously credited with saving the game in 1976.

From roughly the 1930s to the 1970s, pinball was illegal in many major cities, including New York and Chicago. It was considered a game of chance, rather than one of skill. “Because there was that element of machines paying out, it had this gambling stigma to it,” Sharpe says.

That association with gambling comes from pinball’s early predecessor, a French game called bagatelle that is reminiscent, says Sharpe, of Plinko on The Price is Right. In 1976, Roger Sharpe testified at a hearing in New York before the city council and demonstrated that pinball required skill. Like Babe Ruth, he essentially “called his shot,” and successfully aimed the ball where he wanted. It impressed the city council enough that they voted to remove the ban on pinball. Chicago followed suit shortly thereafter.

Despite the fact that playing pinball in Chicago was technically illegal, the city was home to many of the largest pinball manufacturing companies starting in the first half of the 20th century. D. Gottlieb & Co., which was founded in 1927 and remained open for 69 years, made pinball machines on Kostner Avenue in Humboldt Park. Williams Electronics was founded in 1943 on West Huron Street. Bally Manufacturing (the brand still associated with casinos) opened in 1932 and was a major pinball manufacturer for 64 years. The last remaining large pinball company, Stern Pinball, now located in Elk Grove Village, dates back in some form to the 1930s.

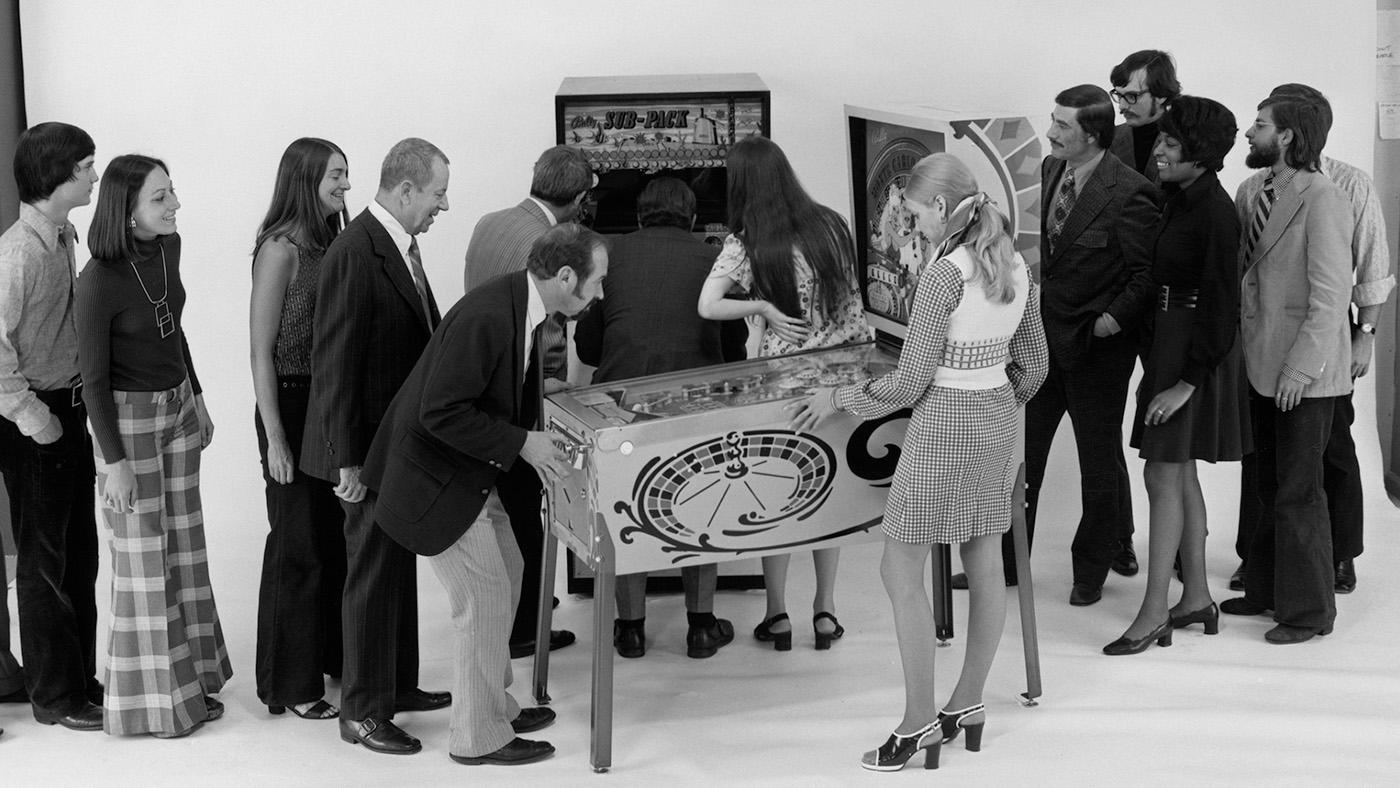

The industry itself has had peaks and valleys. The 1970s was its zenith, with the game both lucrative and popular. “You would have pinball machines literally everywhere in the world, every pizza joint, laundry place, you name it,” Sharpe says.

But as new arcade games, such as Pac-Man and other at-home electronic entertainment, emerged over the next couple of decades, the pinball industry took a hit. Some firms merged with other companies or shuttered altogether. The early ’90s saw another increase in popularity with new pinball games, but once again things tapered off. After weathering the Great Recession, Sharpe says Stern Pinball has seen “year over year growth ever since” 2010. Today, Elk Grove Village is home not only to Stern, but to a company called Jersey Jack Pinball, while companies like the Chicago Gaming Company and American Pinball are also located in the suburbs. There are boutique manufacturers, too.

“It’s become more and more popular,” Sharpe says. “The thing that's cool with pinball in general is this new generation of players. Whether it's competitive or casual, they're growing up with pinball machines in their house, which never was a thing before.”

Part of the appeal of these machines is their design, according to Sharpe. Many pinball machines have recognizable intellectual property as their theme. “If you walk into an arcade, and you had a game side by side, and one was generic space theme, and the other one was Star Wars, what are people going to gravitate towards?” he says. “Whether it's playing on location, or to put in their personal homes, and those licenses – Jurassic Park, James Bond – people have that history with those iconic visuals.” Stern Pinball, for example, just released a new Jaws pinball machine.

“These things are works of art,” Sharpe says. “People love to buy them, and they might not play it too often, but it looks incredible even when it's turned off.” That’s another great thing about pinball: People get satisfaction out of it in different ways. For some, it’s a nostalgic trip back to the arcades of childhood, or even the 3D Pinball Space Cadet PC game. Some play for fun, others competitively. Sharpe says others are “tinkerers” – in the same way that people might tend to a classic car but never drive it, they care for pinball machines displayed proudly in their basements.

For Chicagoans in search of pinball, Sharpe recommends the Logan Arcade in Logan Square and Enterrium at the Woodfield Mall. There are competitive groups, too, including the women’s league Belles and Chimes, which got a write-up in 2023 in The New York Times.

“There's never that same tactile feel where you're battling gravity” Sharpe says. “No ball is ever the same. It's just a unique experience that just can't be replicated.”