Wilshire Boulevard

Wilshire Boulevard

Discover the story behind the development of L.A.’s “Miracle Mile,” a revolutionary new shopping district catering to motorists in what was once considered “the suburbs” of the city.

In the early twentieth century, Los Angeles grew at a staggering pace.

“No one has ever seen growth like this,” said Reed Kroloff, architecture historian. “It goes from almost, literally, nothing, to being a city of millions of people in thirty, forty years.”

That growth occurred in tandem with the rise of the automobile in American culture, making LA the first major American city in which cars were a central part of the city’s design.

“The car actually controls the development of the city, and the Miracle Mile is a perfect example,” said Kroloff.

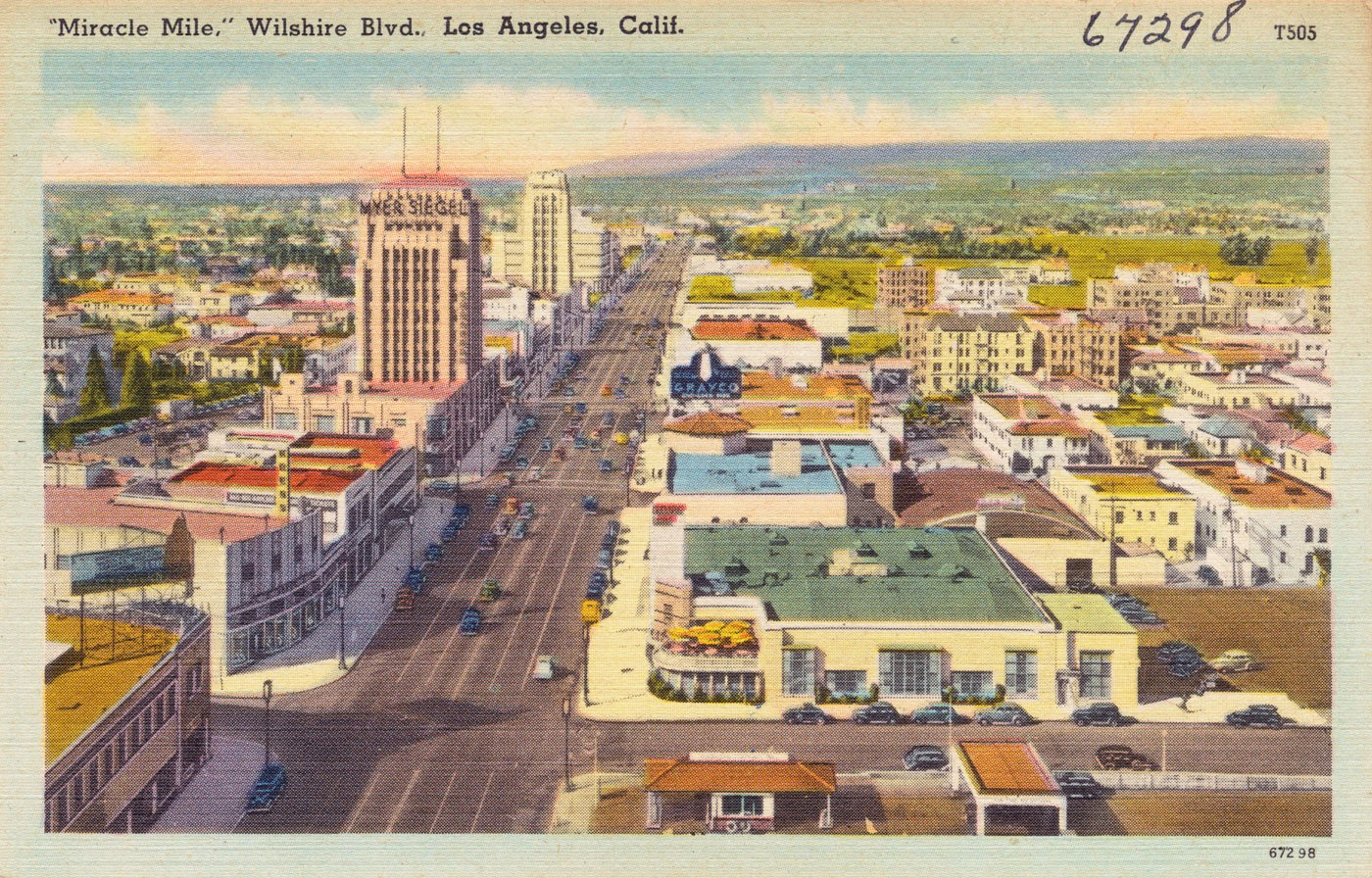

The plan for the Miracle Mile was to transform a dirt road in the suburbs into a ritzy shopping district. It initially seemed so preposterous that one real estate developer later suggested that its success was nothing short of a miracle, thus the name.

Developer A. W. Ross had an ambitious vision for that stretch of land just west of LA’s city center. He knew LA was destined to sprawl towards the ocean, and he saw a fortune to be made.

He wasn’t the first. In the late nineteenth century, an outspoken and eccentric socialist named Henry Gaylord Wilshire had recognized that Los Angeles would one day likely expand towards the sea. In 1887, Wilshire purchased a thirty-five-acre barley field west of Los Angeles for $52,000 and developed it into a residential subdivision with a wide, central boulevard, which bore his name.

But it took nearly two decades – and the rise of the automobile and the streetcar – for Wilshire’s prediction to come to pass. In the 1910s and early 1920s, other developers began purchasing old ranches and transforming them into high-end residential subdivisions.

But residents of those areas still had to travel downtown to shop. And that’s where real estate developer A. W. Ross saw an opportunity, says J. Eric Lynxwiler, who contributed research for Wilshire Boulevard: Grand Concourse of Los Angeles.

“He realized that these housewives may not want to drive all the way to downtown in order to do their shopping,” said Lynxwiler. “He decided that he would build a commercial center.”

Wilshire Boulevard had been constructed for the horse and carriage but was built wide enough that a coachman could make a 180-degree turn in the street. Ross saw that the width would make it ideal for car traffic.

Yet the odds were not in his favor.

For one, outside the residential areas, the boulevard was dumpy, surrounded by barley fields, oil derricks, and airfields.

In addition, there were powerful interests in LA’s central business district that weren’t too keen on the idea of competition. They succeeded in having LA’s City Council zone the entire area Ross was interested in developing for residential use only.

“There were a lot of people who were actually actively working against A. W. Ross developing the Miracle Mile,” said Lynxwiler. “They tried to shut him down.”

It made it hard for Ross to drum up the interest he needed to attract funding.

“Regular investors wouldn’t even let me tell my story,” Ross later said in an interview quoted in the 2005 book Wilshire Boulevard: Grand Concourse of Los Angeles by Kevin Roderick. “Even friends who had the means to help me laughed and wished me luck.”

But Ross forged ahead. He continued purchasing land and making plans.

He got around Los Angeles’s zoning laws through piecemeal permits. “He would take that piece of property and the promise of that property [to] the City Council and then convince them, one building at a time, to allow him to construct something commercial,” said Lynxwiler.

The secret to his success laid in the stunning buildings he proposed.

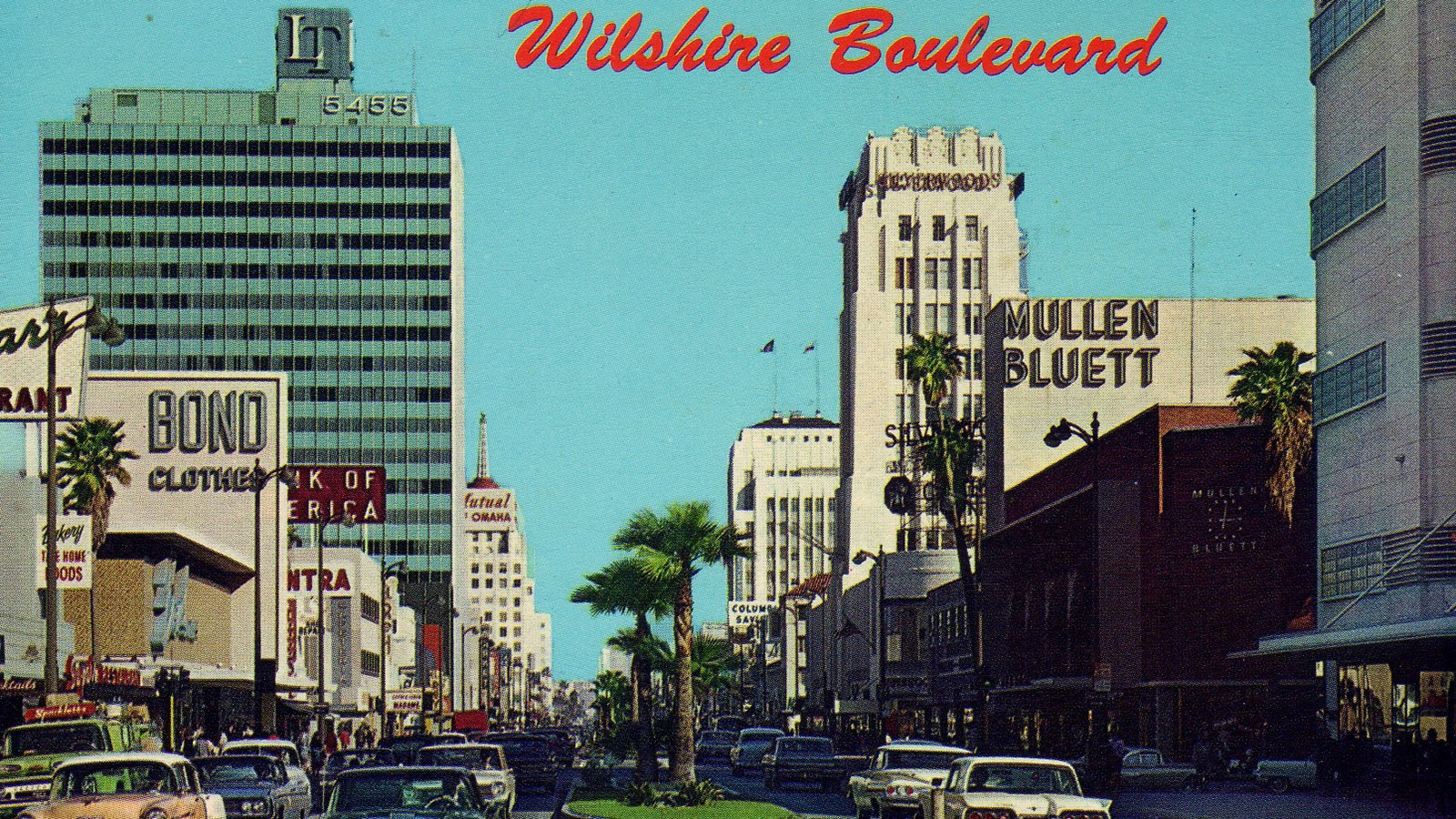

“He knew that a gorgeous building, built in an art deco style, which was popular at that era, would win over the City Council of Los Angeles,” said Lynxwiler. “So that’s why Wilshire Boulevard had some of the most gorgeous art deco buildings on it.”

And eventually, he attracted partners with whom he built speculative commercial buildings, including the Wilshire Professional Building, the boulevard’s first skyscraper, in 1929. They actively courted high-end tenants, including the fashionable men’s clothing retailer Desmonds, to help set a tone and attract other prospective vendors.

Ross established a host of guidelines for new construction, all with the goal of enhancing the driving experience along Wilshire Boulevard and making an impression at 30 miles per hour. He wanted the buildings to be grand in stature, what Lynxwiler called “beacons in the middle of flat plains.” Ross also requested space for parking but preferred for those parking lots to be tucked away, behind buildings and out of view of drivers.

“It’s one of the first times where one developer is in charge…and has control, almost zoning-like control over what the buildings are going to look like,” said Kroloff. “He is anticipating a city life where the car is going to be the driver of this development.”

And it worked. Wilshire became a destination – and one where, contrary to other shopping areas, the sidewalks were rarely used.

“The saying is, you could shoot a cannon down the sidewalk on the Miracle Mile and not hit anybody because they were all accessing the stores from the parking lot,” said Lynxwiler.

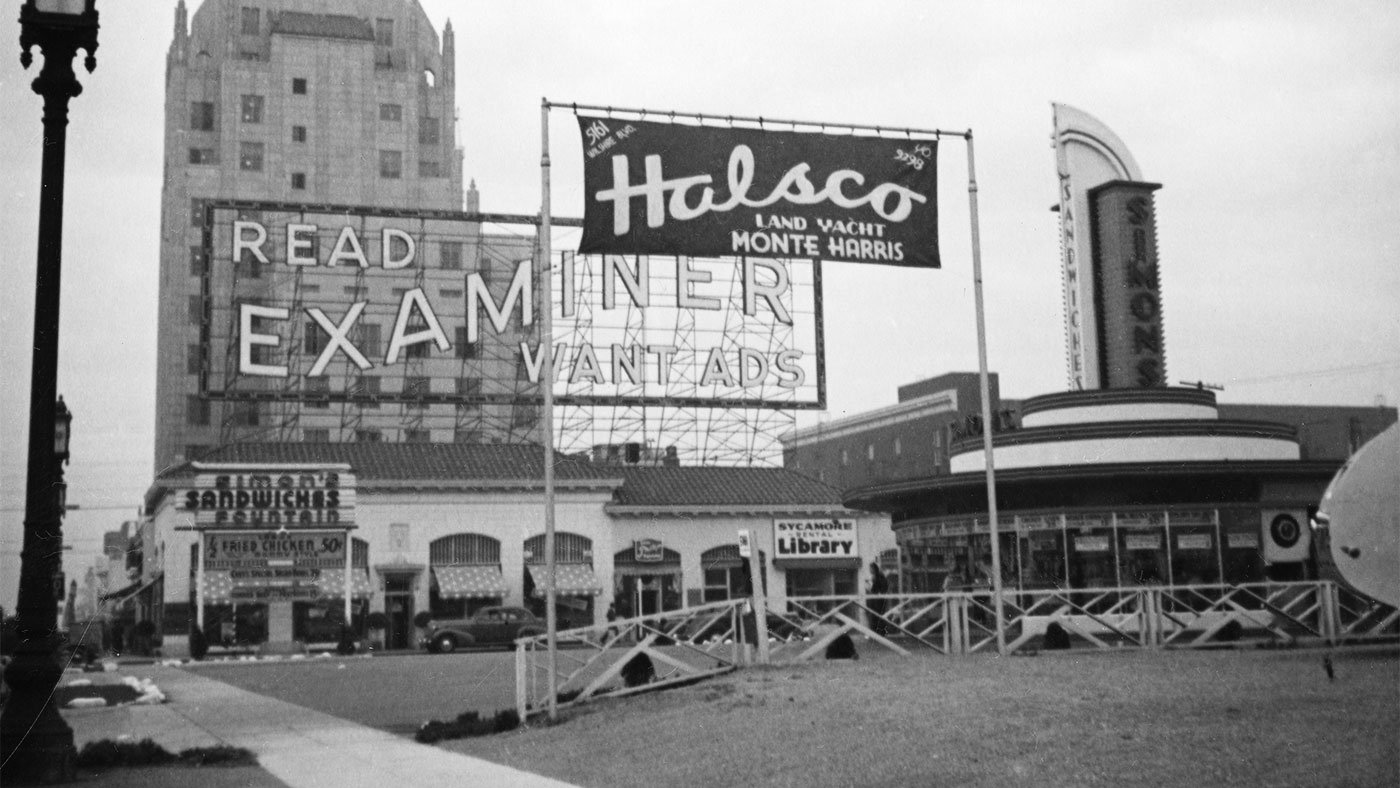

Ross also required that construction and advertising along Wilshire be engineered for optimum viewing through a windshield. That meant, among other things, bold signage and massive buildings with dramatic ornamentation.

Dozens of businesses erected large, neon signs on top of their buildings, which could be seen for miles around.

“He wanted to create a spectacle for the motorist,” said Lynxwiler, “in order to get them to stop their car and get out.”

Some of the buildings caught the eye by mimicking objects, often the products they sold, in an architectural style that became known as “California Crazy.”

“It’s visually exciting,” said Kroloff. “And it has all the right shops and restaurants and offices, so you want to work there and maybe you want to live in the neighborhoods that are right behind there.”

The car, and the Miracle Mile designed for it, had successfully moved pedestrians out of the city center and off the street. In doing so, it reorganized how people traveled and interacted in urban spaces, prompting new patterns of movement and interaction, as well as styles of architecture and advertising that continue to this day.