Photo by Brian Canelles.

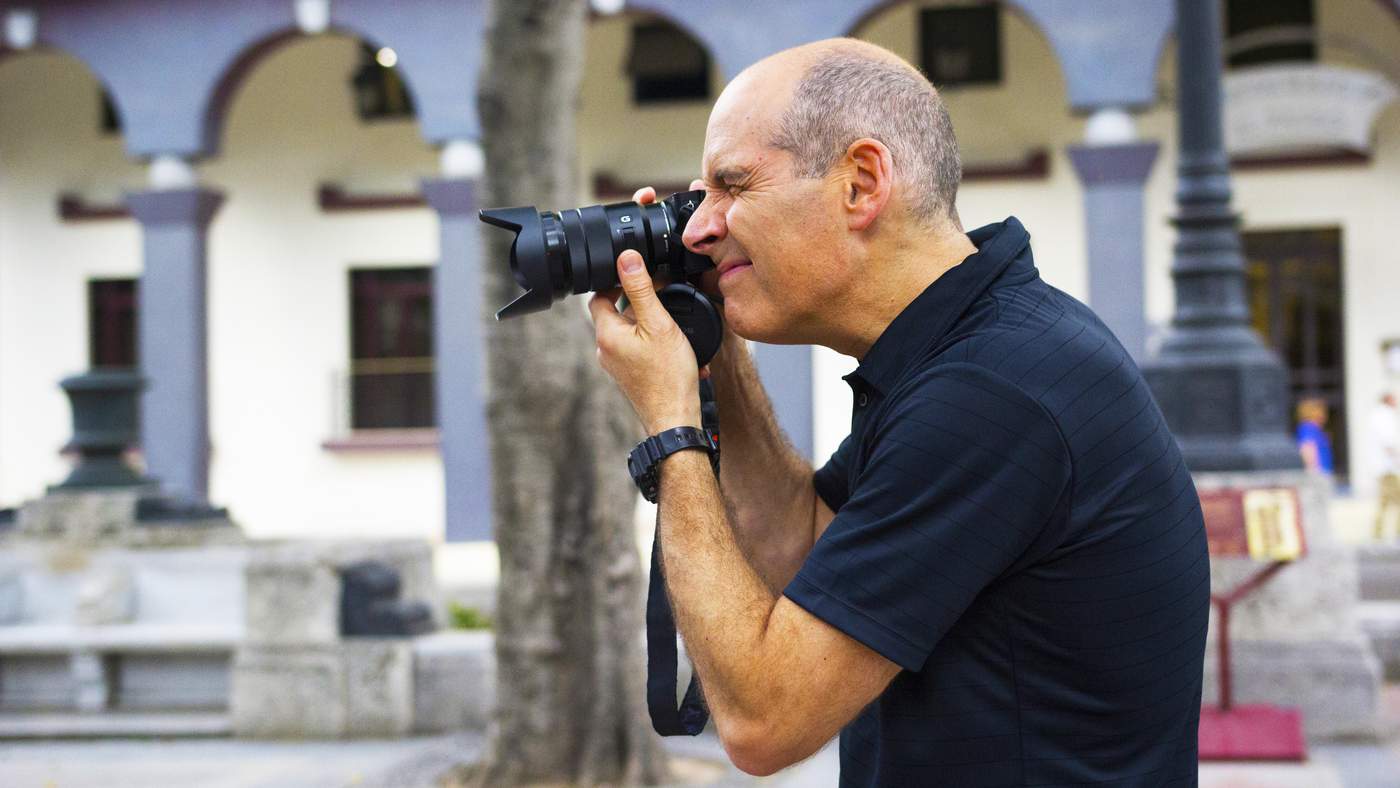

Geoffrey Baer’s Travel Journal — The Scouting Trip

Weekend in Havana was filmed over 16 days in November and December, 2016. Prior to filming, Geoffrey and the production team visited Cuba for several sweltering days in August 2016 to scout locations, meet potential interviewees and plan their production. It was Geoffrey’s first experience in Cuba and he documented it day by day in this journal.

DAY ONE

DEPART MIAMI FOR HAVANA

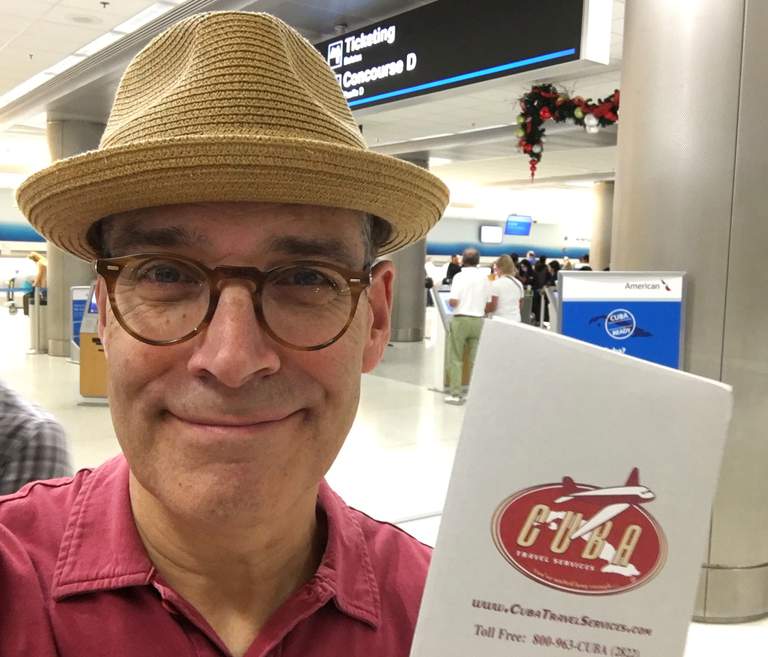

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

At Miami Airport waiting to check in for the short hop to Havana, I feel excitement and trepidation. Excitement about visiting a place I’ve never seen (or really even dreamed of seeing). A place shrouded in myth and mystery for half a century. Trepidation about so many things. Regular flights have not yet begun, so we’re flying charter. Will there be a glitch in our paperwork that will prevent this journey from even happening? Will I, with virtually no ability to speak Spanish, be able to navigate the idiosyncrasies of Cuba? I’m a bit of a germophobe and fret about food safety, drinking water, and clean bathrooms.

In the crowded check-in area are many families clearly of Cuban heritage bringing goods to their relatives on the island. Giant shrink-wrapped and labeled bundles of things not easily available in Cuba: TV sets, computers, small refrigerators, window air conditioners, and suitcases stuffed with clothes and heaven knows what else. Medicine? Food? Sporting goods? This raises the first of many, many questions I’ll have about how things work in Cuba. Does the government encourage such imports? Look the other way? Carefully inspect everything?

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

I’m traveling with my boss, Dan Soles, WTTW’s vice president and chief television content officer. His parents fled Cuba the day after they were married in January 1961. This is Dan’s first visit to the island, and he has dropped his usual reserve: he is clearly bursting with excitement and anticipation. Like so many others on the plane, he eagerly looks out the window for a first glimpse of the Cuban shoreline.

When our wheels touch down, the passengers break into applause. As we taxi to the terminal, we pass jets from Angola Airlines and Russian Aeroflot. We also see rusted hulks of old airliners decaying in the grass. They’ve been stripped for parts, presumably to keep other airliners flying.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

We deplane on the tarmac via boarding stairs. No jetways at the big old shed that serves as the arrival area for flights from the U.S. Exiting the plane, I take photos of Dan setting foot in Cuba. He gives a triumphant and joyous wave to the camera.

For the record, I had absolutely no problems getting through Passport Control and Customs. And my favorite detail is that all the border control agents were young women whose uniforms were stylish, brown mini-dresses with black fishnet stocking in various patterns. Unfortunately, they did not permit me to photograph them. The wait for our luggage is interminable. We wonder if every bag and bundle is being opened and inspected before being sent down the conveyor belt.

After dropping off our bags at our lodgings, we meet up with Leo Eaton, the director of our documentary, and the rest of the production crew at the first of many paladares we’ll dine at while in Cuba. These are private restaurants that were illegal until the 1990s. Many were in people’s homes. This one is called Atelier. Like many paladares, it’s beautifully maintained, tasteful, and stylish. And the food is great! I innocently ask if it’s locally sourced, and my tablemates laugh at me. Where else would it come from? I’m not much of a drinker, but these meals are virtually always accompanied by more than a few mojitos and/or piña coladas.

Photo by Brian Canelles.

After lunch, we take a whirlwind tour of Habana Vieja, or Old Havana. It’s HOT and sunny. I slow everyone down by taking lots of pictures. We see all four historic plazas. I’m speechless at my first view of Plaza de la Catedral presided over by the eponymous edifice in all its baroque glory (which I later discover has a Romanesque interior that appears like a soaring cave because of the rough character of the local limestone). It’s an austere, contemplative, soaring, vaulted space with wonderful statuary, including a startling likeness of Pope John Paul II that looks as though it could turn its head and start giving us a blessing at any moment.

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

Next we head for the Parque Central Hotel to use the internet. This will become a familiar ritual. No access to internet using cellular data on our smartphones, and Wi-Fi is available only in hotspots like the Parque Central. If you want to get online, you buy an internet card at a hotel or one of the sporadically located kiosks on the street. (That is, if they are open, the line isn’t too long, and they haven’t run out of cards.) Before leaving for Cuba, I downloaded an app called Viber that people use to communicate: Facetime doesn’t seem to work, and phone calls are, of course, expensive! I call my family back home. The video chat doesn’t seem to work, but we can hear each other. I tell my wife it feels like I’ve been in Havana for a week already. Such a total immersion. I post a picture on Facebook of me in the Cathedral Plaza. “No, I’m not in medieval Europe, I’m 90 miles from the U.S. in Havana…” I’ll have to wait 24 hours to find out how the post does. Soon enough I’ll come to appreciate being off the grid and not tied to my iPhone for a week.

DAY TWO

We drive to Hemingway’s house, Finca Vigía, an hour or so outside Havana. This gives me a glimpse of the countryside and small rural towns. But when we arrive, the gate is locked, and the attendant tells us it’s closed on Sundays.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

So instead we visit Cojímar, a nearby fishing village where Hemingway kept his boat, the Pilar. There’s a rusty drawbridge at the harbor entrance with an old electric motor. Moves so slowly we don’t realize at first that it is operating. People continue to walk across it as it slowly opens to allow a fishing boat to pass underneath. Just one of countless examples of conditions that would give an American lawyer a heart attack (or a field day, depending on which side s/he took). It turns out the bridge opens only about six inches. Just enough for the boat to clear below as the fishermen duck their heads and grab the bridge to guide the craft underneath.

I watch and photograph a few more fishermen coming back to harbor in their boats.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

Back in Havana, we visit the cemetery Colon. A whole history of pre-revolutionary Havana wealth sprawls out. A cemetery employee hustles Dan Soles for a tip by climbing into a crypt and emerging with a human leg bone. “Femur” becomes a running joke among us. Some of the statuary adorning the tombs is really breathtaking.

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

DAY THREE

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

Off to meet the U.S. Ambassador (actually, his title is chargé d'affaires) Jeffrey DeLaurentis at the ambassador’s mansion. Pass through a very well-kept and clearly wealthy district. Seems like Embassy Row. Guard posts at every corner (although unmanned).

On our way, we pass the former Soviet, now Russian, Embassy. If ever there was an archetype of oppressive Soviet architecture, this is it! A brutalist concrete extruded box soaring perhaps 15 stories. Near the top is what can only be described as a glass watchtower. Several floors of windows ideal for surveillance. This is capped by a bizarre, ungainly ornamental top. I wonder if it is (or once was) filled with all manner of communications antennae.

We turn off the main drag onto a winding, wooded lane and arrive at the ambassador’s residence, complete with the Great Seal on the brick gatepost. A very cheery protocol officer wearing a white, traditional Cuban shirt and giant, wraparound sunglasses welcomes us and says the ambassador is en route from the Embassy. In short order, he arrives in his SUV and we’re escorted into a lavishly, if outdated, furnished drawing room. Ambassador DeLaurentis has a deft ability to be at once warm, relaxed, informal, and also patrician and political. He spends a lot of time giving us a long description of our interests in Cuba and how we’re pursuing them (and have achieved many). And acknowledges some of the missteps of his predecessors, such as installing an electronic propaganda signboard atop the embassy on the Malecón (Havana’s waterfront highway). The Cuban regime retaliated by blocking it with a forest of flagpoles and constructing a plaza adorned with bold patriotic inscriptions; throngs of Cubans demonstrated here in organized anti-American rallies. He also gives us a lengthy description of the mansion, throwing doubt on the legend that it was built as a getaway for FDR.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

Next we drive more than an hour out into the countryside to look for the ruins of plantations and slave history. Our Cuban “fixer” Boris knows generally what we are looking for and has seen and visited them in the past. No GPS or other smartphone guidance here. Our driver pulls up alongside various pedestrians along the rural roads (some dirt roads) asking for directions. And most people are quite helpful! It’s amazing to me how pedestrians are everywhere. Walking along rural roads and the equivalent of Cuban interstates, hitchhiking, waiting for buses, and just hanging out. They carry bundles and children. Often there are no sidewalks, and the pedestrians use the right-hand lane or edge of the road (rather fearlessly). In addition to pedestrians in the slow lane and along the edge of the road, we pass three-wheel bicycles, horse carts, and motorcycles with sidecars. On reflection, it makes perfect sense. Few people have cars, and the ragtag array of public transport can be infrequent and unreliable. This also makes me think about the communal culture of this country. People pick up hitchhikers and readily give directions to strangers. It’s almost as if they all know each other.

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

We succeed in finding an overgrown, former plantation with a tower from which overseers could watch the slaves. The bell once used to call the slaves in from the fields is still up there. The ruined buildings are amazing. Overgrown with towering trees the roots of which creep down the walls. If you saw this in a movie, you’d say it was a fantasy. Someone once promoted this as a tourist attraction. A crude sign nailed to a tree advertises Ruina.

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

Back in the van on our return to Havana, we pass through the capital of rural Artemisa Province.

A dusty town of crumbling, one-story, colonial-era buildings fronted by colonnades that shade the sidewalks just as in Havana. Here the columns are more slender and spindly, but many still sport ornate Corinthian capitals and cornices. The streets are filled with pedestrians, three-wheel bicycles, horse carts, dogs, and various trucks that serve as city buses. We disembark to find soda or water. I wander off to take pictures and lose the group. Momentary panic. I don’t speak Spanish, and frankly, even if I did, I wouldn’t know how to tell someone where I am staying in Havana or how to reach them. Thankfully, another of our producers, Donn Rogosin, finds me and walks me a couple of blocks to where the others have found a place to get canned lemonade (no bottled water available, apparently).

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

On the road back to Havana, I photograph more makeshift “buses.” They look like semi-trucks hauling human cargo. Boris says most drivers/owners modified the trailers with their own hands.

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

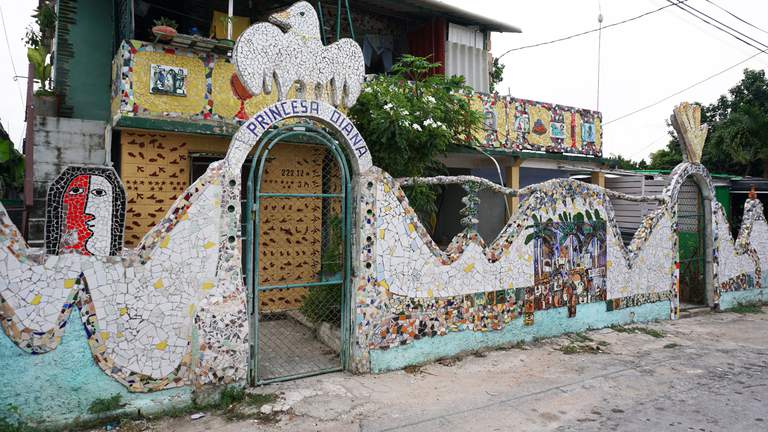

Back in Havana, we stop at a neighborhood where artist Jose Fuster has tiled the walls of buildings for several blocks around his house with fanciful mosaics. One mosaic says it’s a tribute to Catalan artist and architect Antoni Gaudí. But I’m not so sure it reaches that standard. We definitely see references to Cubism. Pro-revolution political imagery such as a mosaic of Fidel and Che in the Granma, the now legendary yacht they rode during their initial 1956 invasion. And there’s a large mosaic depicting Hugo Chávez. As we leave the neighborhood, I note that even two of the local bus shelters have been encrusted in mosaics.

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

DAY FOUR

Our whole production team heads out this morning to tour more of Habana Vieja, or Old Havana, with Daniel de la Regata. He’s a restoration architect who formerly worked with historians of the city. He will be one of my on-camera “guides” in the show. Daniel is lively, young, and hip and not shy about sharing his opinions and knowledge. Very passionate about the complex issues of restoration and impact of opening of relations with the U.S. He and I hit it off immediately. We could riff about architecture, restoration, and history endlessly. He clearly has such pride in the restoration work that has already been done. And no illusions about how much is still to be done He doesn’t buy the myth that as things open up between Cuba and the U.S., we all need to hurry to Cuba to see it “before it all changes.” He tells me he doesn’t think it can change quickly. There is just too much to be done, notably the woefully decayed infrastructure needs to be almost completely repaired or replaced. And he thinks change needs to happen slowly anyway so that Cuba’s unique culture can be preserved.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

One thing that really sticks with me is the way that people living in overcrowded Habana Vieja have sometimes subdivided their apartments VERTICALLY because old buildings had tall ceilings. They create sweltering lofts that Daniel says are called barbacoa, or “barbecues,” because heat rises. In one place, residents have sliced right through upper portions of tall nineteenth century doors to create barbacoa lofts. We see many people crowded into these makeshift homes. Around the corner in the same building are soaring cast-iron doors with lion-head knockers and inside a paladar! More of the amazing juxtaposition that is Havana.

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

In general, Havana is a museum of architectural styles, all frozen in time because of the embargo. Although much is made of the more showy art deco and historical styles such as neo-classical and baroque, I’m most struck by the early modernist architecture (which is everywhere). Because of the clean, minimalist lines, this style seems most dramatically altered by deterioration. Bus shelters all over town are little gems of mid-century modernism.

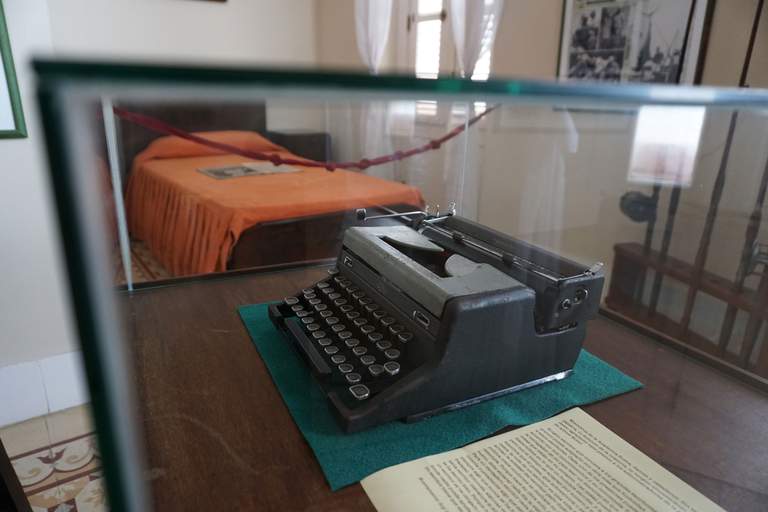

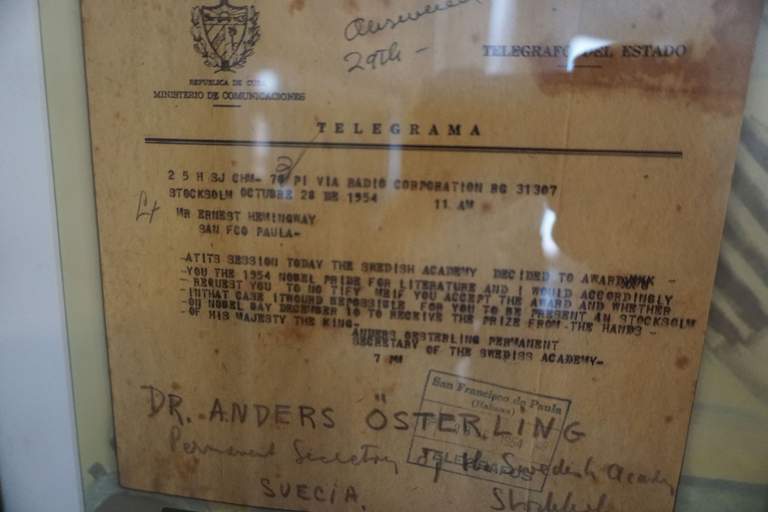

After lunch, we do a quick romp through the Hemingway sites. Among them is his room in the Hotel Ambos Mundos where he wrote several works. Hemingway lived in Room 511 in this hotel throughout the 1930s. The room is now preserved as a tiny museum with Hemingway’s typewriter under glass (at least they claim it was his typewriter) and the actual telegram framed on the wall notifying him that he won the Nobel Prize for Literature. He received it in 1954, long after he moved from the hotel to Finca Vigía.

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

We swing past the soaring Edificio Bacardi in all its faded deco splendor. During Havana’s boom times in the 1920s, the Bacardi Company built this showpiece of a skyscraper as their fame spread worldwide. And Prohibition-weary Americans flocked to a country Bacardi promoted as “the land of rum.”

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

As we continue to explore grand buildings from the 1920s, we stumble upon a fellow in a plaza with a homemade, old-fashioned view camera. Director Leo Eaton had seen him on a previous trip to Cuba, and we’ve been looking for him for the last few days! He’s one of the last of such photographers who used to stand outside popular Havana landmarks and offer to photograph tourists. So of course we ask him to take our picture. We draw a crowd as he fiddles with the lens and frames the shot. It reminds me of my dad endlessly focusing his old Speed Graphic camera for family pictures when we were kids. The photographer instructs us to stand very still, and instead of clicking a shutter (there is none), he simply removes the lens cap, counts to four or five, and replaces it carefully so as not to shake the camera. He then makes a paper negative, which he develops it in a drawer full of chemicals cleverly mounted under the camera (by feel, of course, since light would instantly ruin the negative). His next step is to photograph the negative and develop that image to create the final photo. But before he can finish, a sudden torrential downpour erupts. One of our producers, Hugo Perez, stays behind in the rain as the rest of us run for shelter. Hugo later tells us he arranged to pick up the finished photo, but he never again found the old photographer.

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

DAY FIVE

We take a whirlwind tour of some of Havana’s legendary hotels from the heyday of American tourism. Many were built or run by American mobsters.

The Hotel Nacional from 1930 was designed by famous New York architects McKim, Mead and White. Amazing sensitivity to local tradition in the architectural design. Doors have a motif that echoes the wooden balustrades of colonial buildings. Wood-beamed ceiling reflects colonial tradition. I notice delightful motifs in the building ornament: waves and sailing ships. This hotel hosted an infamous mob “summit” in 1941 attended by Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky, and others.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

Next, we stop at the Riviera. A real mid-century modern gem built by Lansky. Feels like I just stepped onto the set of Mad Men. The dining room decor, the red doors (locked) to a ballroom, the front desk, and especially the pool with its swoopy, three-level high dive. On the way, I notice a defunct fountain with mod-looking concrete sea creatures. I’ve seen many fountains around the city, but none are turned on. I later learn that this is partly because of water conservation issues but mostly because they break due to defects and poor maintenance, and replacement parts cannot be found. And when they break, the water becomes stagnant, and the fountains become breeding grounds for mosquitos. So virtually all are drained.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

Last, we visit the Habana Libre hotel. It was built as the Havana Hilton, but opened just before the revolution. Bad timing! It has a huge Dubuffet-esque mosaic over the entrance. Inside a dome soars overhead perforated by circular skylights. Pretty nice for a government-run hotel until we discover the public bathrooms are locked and inaccessible to the public. And there’s no WiFi. Behind a partially finished, sheetrock wall in a side room, Dan buys our tickets for tonight’s performance at the Tropicana.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

Next we explore El Centro, or Central Havana. It’s like a shock to the senses. Unlike the historically more upscale neighborhoods of Vedado and Miramar, the buildings in Centro are built right out to the street. Arcades line the main streets providing some shade, but side streets have no arcades and feel like walled canyons. We snake slowly through streets filled with all kinds of vehicles and people. Crumbling ruins are everywhere. Seems like almost none of the buildings have been restored. And here and there, buildings have simply collapsed.

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

Then we hurry in the van through the tunnel under the harbor over to the Hershey train. It was built by the American Hershey Company around 1917 to serve their sugar refinery several hours outside of Havana. I totally geek out on this ramshackle relic. A rusty, old, single, electric interurban car. It’s standing in the station awaiting departure time. The train crew and a few passengers lounge about in the station shelter under a sloping mid-century modern roof. An agent sits in the forlorn ticket booth. Since the train isn’t going anywhere anytime soon, Leo, Dan, and I climb aboard. Talk about “mind the gap.” The concrete steps are a good six inches away from the threshold. The years have taken their toll on the interior. Old plastic seats sit on metal frames that look like they could be homemade. I photograph the worn-looking motorman’s console. A bunch of lightbulbs or fuses seems to be simply missing.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

I look at the timetable with Boris. It’s handwritten with dry-erase marker on a wall-mounted board. The train leaves at 4:30. The first stop is Hershey an hour and a half later. And the only other stop is the end of the line another two hours beyond that. But Boris says the train will stop if you just flag it anywhere along the line. I think of the hitchhikers doing the same thing with cars along the country’s highways. Seems like the standard way to travel Cuban-style.

We had thought the train was leaving at 4 p.m. So we decide not to wait. Instead, we walk across the parking lot to catch the ferry. As I step off the curb, I find there is no pavement under my foot. Just a big hole. And I fall straight down. Crumbling pavement is common all over Havana. I only let my guard down for a moment, but it costs me. I’m holding my camera in my right hand, so I twist my body to avoid smashing the camera on the ground and take the impact with my left palm and right elbow. Fortunately, no major damage (to me or the camera). A bit of a scrape on the elbow and a little pavement burn on my palm. I clean the wounds with some wet wipes I conveniently remembered to bring along. I also have Band-Aids, and Dan Soles applies them to my elbow. Boris tells me I’m a celebrity. All the Cuban passengers in the ferry terminal are asking him if I’m OK! The ferry terminal is just a little, hut-like building. Our bags are inspected, and we are wanded by security before we board the little vessel. It’s basically an entirely enclosed, small, metal box with handrails across the ceiling. I have no idea where the captain sits. Maybe on top? But there’s no wheelhouse up there.

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

There are a few windows, which passengers peer through. And the two doors on starboard and port are just wide open with a piece of rebar put across to block the way. I photograph a young boy standing at one of the doors as we ply the harbor to the other side. He could easily have slipped right underneath the bar and into the water if the sea had been at all rough. If there had been more windows or a deck to stand on, the view of the Old City would have been pretty good. As it was, I got some great shots of people with the crumbling piers of Old Havana in the background.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

Once docked, Dan Soles and I hop a coco taxi. Yes, everyone wants to ride in the ubiquitous 1950s convertibles. And that’s definitely fun. But I liked these even better. They are essentially motorized rickshaws with a driver sitting behind handlebars and just enough room for three people in back. They’re shaped like yellow fiberglass coconuts (hence the name). Dan filmed the entire coco taxi ride on his iPhone with a huge smile on his face.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

The smell of exhaust is EVERYWHERE. When I visited China, it was cigarettes. Here it’s hydrocarbons. Cars and buses and even tiny motorbikes spew clouds of blue and gray smoke. Enormous chimneys visible on the skyline belch smoke from coal-fired power plants and giant flames of burning methane from oil refineries that dissolve into the blackest of black smoke and drift high across the city.

We pass many sites we had seen previously from the windows of our van, but we agree that the open-air coco taxi offers an even better view of things (if somewhat more life-threatening). Amazing juxtapositions between the conditions of a developing nation and opulence. Often in one block and not infrequently in one building.

A little later, we visit the house Dan’s mother lived in until she got married and fled Cuba more than 50 years ago. He has been calling her every night on my phone giving 2-minute updates so she can experience the visit through his eyes. She described the house and gave him the address. When we find it, he is truly overwhelmed with emotion. I photograph him in front of the building.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

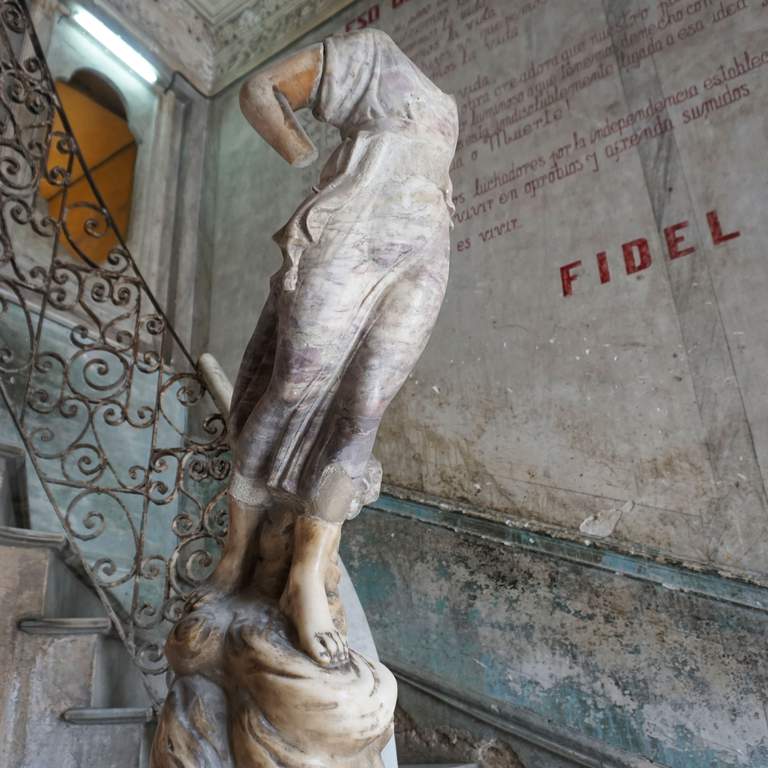

Off to dinner at La Guarida, the most amazing of all the paladares we’ve seen. It’s on the top of a ruined palace. When it opened 20 years ago, dozens of families were squatting in the carved-up floors below. Today there are still some living there. But Hugo tells us the restaurant owner has been buying up the units little by little and stabilizing the building. We see the wooden shoring holding up the floors as we ascend the stairway. The rooftop restaurant has a view of the surrounding neighborhood in all its faded glory. But ascend two spiral staircases to a rooftop bar for the jaw-dropping 360-degree vista of Old Havana and the coastline. I am speechless as I survey the sunset view. The food is excellent. Marlin tacos, rabbit pâté, and a wonderful watermelon gazpacho for appetizers. Delicious dish of red snapper for the main course.

Photos by Geoffrey Baer.

Then we hit the Tropicana for a real throw-back experience! The legendary cabaret club is truly frozen in time. The performance space is outdoors under soaring trees. Stars are visible in the sky. Our ticket price includes champagne and full bottles of rum and mixers. Plus a few peanuts. The performance is what one would expect. Lavishly lit and costumed. But it’s immersive, too. The performers are all around us. On a stage with many levels, on a three-tiered wall in the distance to audience left, on a runway up and behind the audience to the right, and often in the audience itself! The live band up in the trees to the right is fantastic.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

The first big numbers are the sort of corny cabaret stuff one probably saw in the ’40s and ’50s. The dancers and singers are excellent. The costumes scanty to reveal PG-13-rated glimpses of bottoms in fishnets and bellybuttons and bikini tops with tassels. Plenty of sequins and feathery fringe. And of course, the headpieces are outrageous: palm trees, towering piles of flowers, and (my favorite) entire crystal chandeliers with working lights.

Photo by Geoffrey Baer.

But then, unexpectedly, the show takes a turn into social commentary and folklore! There’s a number depicting slaves complete with a brutal, whip-wielding slave driver. Another number presents colonial oppression of the native population. And yet another seems to suggest Afro-Cuban religion. The music here is laced with virtuosic Cuban and African drumming.

Then, just as quickly, it’s back to the frothy review with the obligatory spectacular finale. The encore is a pop singer badly lip-syncing as a few hip-hop dancers cavort around her. Then the MC cajoles tourists from a wide array of countries to come on stage (he calls out countries as the video screen behind him shows flags). He also welcomes people celebrating birthdays. And the show ends in a big dance party with the MC leading the steps to songs from each nationality. It’s like a Cuban bar mitzvah! Dan Soles comments that while Leo’s native country (England) got a Queen song, we got “YMCA.”

MY GUIDES

(left to right) Geoffrey Baer, Irene Rodríguez, Roberto Fonseca, and Daniel de la Regata on the patio at Hotel Nacional de Cuba. Photo by Brian Canelles.

In addition to restoration architect Daniel de la Regata, I will have two other on-camera “guides” in the program: phenomenal Afro-Cuban jazz pianist Roberto Fonseca and flamenco dancer Irene Rodríguez. Unfortunately, on this scouting trip, I meet Irene for only a brief moment on my first day before she has to leave on tour. And Roberto is not in the country at all. Returning to Havana three months later to film the show, I become very close to both of them.

Irene is warm and highly energetic. She is deeply proud of her Cuban heritage and of the dance troupe she has built. I see two distinct sides of her during our time together. In one of our first scenes, she shows me the lively streets of Havana at night, even cajoling me into dancing in the streets (albeit not well). The next day, we film a rehearsal at her dancing school. Before the rehearsal starts, I photograph the lovely young dancers in her studio. Beautiful bare shoulders glowing in the warm light from the windows. Irene transforms from the warm, flirty, young woman I interviewed last night into a firm task master, setting a no-nonsense example for her young protégés as she drills them in dazzling footwork and unbelievably complex rhythms.

Photos left to right by Brian Canelles, Hugo Perez, and Geoffrey Baer.

Roberto is not only a brilliant jazz musician, he is also a devout practitioner of Santería, a religion in which slaves secretly worshipped African deities by giving them the names of Catholic saints. We film a scene about Cuba’s slave history at the plantation I described earlier in this journal. Roberto dives into the whole plantation scene with gusto. He wears all of his Santería beads and a white shirt. In the scene, we are filmed arriving in a horse cart, which Roberto LOVES. He is totally game for jumping in and out of the cart as we record multiple takes. And when we are told there’s no access to the old bell tower, he offers to climb it from the outside (our director, Leo, declines his offer). It is a perfect setting to talk about Santería and the roots of Afro-Cuban culture and jazz. On the plantation is a HUGE ceiba tree, a sacred type of tree used for Santería. Somewhere in the middle of our shoot, a few people show up at the tree and start a Santería ritual. Roberto becomes very excited to record their chanting. They don’t want the ritual filmed, so Roberto asks if they’d just do some chanting for the camera after they finish praying, and they agree. Roberto joins them. It is one of the most remarkable scenes in the film.

Of the three guides, Roberto is the least fluent in English, but he gives me one of my deepest insights into Cuban culture: an immersion in his music. We set up a scene in a legendary Havana recording studio (Estudios Areito), where stars such as Benny More, Josephine Baker, and the Buena Vista Social Club have recorded. He invites me to the piano to tap the rhythm as he plays. Later, he brings a drum over, and I join in a jam session. His bass and percussion players are totally amazing. Something clicks for me. I hadn’t loved Cuba til that moment. But afterward, I started to really feel it. And the run-down surroundings start to look beautiful to me. Or maybe I now more clearly see the beauty beneath the run-down surface.

Roberto Fonseca and Geoffrey Baer outside of Estudios Areito. Photo by Alice Arnold.

The trepidation I felt at the beginning of the trip is gone; thanks to my guides, and so many of the people I’ve met, Cuba now feels like a friend.