Virtual Tour of Havana | Weekend in Havana with Geoffrey Baer

Welcome to Havana

Please use headphones

for the best experience

Cuba is a feast for the senses — a place with rich traditions in music, dance and the visual arts, where classic cars rule the roads and architectural marvels line the streets…

Explore the sights, sounds, and history of Cuba in this virtual tour of its capital city.

Day 1

Begin your trip with a stop at the historic Hotel Nacional de Cuba, which harkens back to a time when Havana was exalted as the “Paris of the Caribbean,” and the premiere tropical destination for America’s rich and famous.

Built in 1930 and designed by the legendary American architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, the Hotel Nacional has seen it all. It was the site of a violent battle between government and insurgent forces in 1933, hosted an American mafia summit in 1946, and counts among its former guests legions of heads of state and Hollywood stars, from Winston Churchill to Frank Sinatra.

Hotel Nacional de Cuba. Photo courtesy of Refreshment_66 / Flickr.

Wander through the majestic art deco building to the palm-shaded veranda in the back, where guests sip mojitos while overlooking the Malecón — the esplanade, seawall, and six-lane highway that stretches more than five miles along Havana’s coast.

The hotel is full of surprises, including an old bunker-turned-museum on the lawn, which tells the Cuban side of the 1962 missile crisis.

Left: Hotel Nacional de Cuba veranda. Photo by Brian Canelles; Center/Right: Photos courtesy of Natalie Marchant / Flickr.

Hop in a taxi and head across the Havana Harbor to the Fortaleza de San Carlos de la Cabaña, one of the largest forts built by Spain in the New World. Be sure to cross the bay in time to watch the sun set on Havana.

Most of the eighteenth century fortress complex is open for the public to explore. At the main entrance sits an open air market, where locals sell handicrafts to tourists. Around the corner is a clearing that has been transformed into an outdoor bar and patio. Other corridors lead to a secret garden, a small museum dedicated to the history of warcraft, and a restaurant serving traditional Cuban, or criollo, food.

Fortaleza vendors. Photo by Brian Canelles.

One room pays tribute to the guerilla fighters who, shortly after the revolution, turned this same fortress into a massive detention facility that held hundreds of political prisoners in the early days of the Castro regime.

Every night, in an elaborate ritual that dates back centuries, soldiers fire a cannon at precisely 9 o’clock. During colonial times, the sound of the cannon fire warned Havana residents of the onset of the citywide curfew and the closing of the city gates. Scores of locals still come to witness the spectacle, and hear the booming blast. It is a reminder that as much as Cuba moves into the future, it still has its feet firmly planted in the past.

Left: Photo by Geoffrey Baer; Right: Photo by Brian Canelles.

After the ceremony, head back to Havana to take in some of the music for which the city is known. Any night of the week, music emanates from just about every restaurant along Calle Obispo. The cobble-stoned street in Habana Vieja, or Old Havana, is permanently closed to vehicles so that tourists and locals can wander, mingle, and spend the night dancing to Afro-Cuban rhythms and son, the traditional style of Cuban music made internationally famous by the Buena Vista Social Club.

Left: Havana shops are open late; Center: Main thoroughfare in Old Havana; Right: Libreria Victoria. Photos by Brian Canelles.

El Floridita bar. Photo by Brian Canelles.

Shops in this area stay open late. Be sure to stop by Libreria Victoria, a small bookstore on Calle Obispo with a rotating collection of political prints by local artists.

At the end of the street is El Floridita, a nearly 200-year-old bar that was reportedly Ernest Hemingway’s favorite place to enjoy a daiquiri. He has been immortalized with a life-sized statue permanently claiming his space at the bar.

Day 2

Begin your morning at Plaza Vieja, one of Habana Vieja’s largest and most extensive restoration projects. The government-owned Café el Escorial roasts its own coffee beans and has a large outdoor patio on the plaza.

Kids at play in Plaza Vieja. Photo by Brian Canelles.

Given the density of Havana and the lack of green space, several local schools also use this open plaza as their playground.

Plaza Vieja is a quintessential example of the transformation Habana Vieja has gone through in recent decades, in large part to attract more foreign tourists, and foreign investment, to Cuba. The entire centuries-old plaza fell into disrepair before the revolution and, in the mid-twentieth century, was turned into a large underground parking garage. It took construction crews nearly 16 years to complete the restoration work, which included completely recreating the central white Carrara marble fountain, which is an exact replica of the original, designed by Italian sculptor Giorgio Massari in the eighteenth century.

Many of the upstairs units lining the square are still residential, and are providing attractive and much-needed private rental units for tourists. Retail dominates the ground floor and includes not only the state-owned coffee shop, but also a micro-brewery, a small museum dedicated to the history of card playing, and luxury foreign-owned stores, including Benetton and Lacoste.

Monument to the Victims of the USS Maine. Photo by Brian Canelles.

Afterwards, hop in a coco taxi and head west down the Malecón, driving past the Monument to the Victims of the USS Maine, a reminder of a much different time in U.S.-Cuban relations.

During Cuba’s fight for independence from Spain in 1898, a massive explosion destroyed the USS Maine, a battleship the U.S. Navy had sent to Cuba to protect U.S. interests during the war. The blast killed 260 crew members and the event precipitated America’s entry into the conflict, which then became the Spanish-American War.

The monument itself has a storied past. An eagle that used to sit atop its Corinthian columns was removed by demonstrators after the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961. The body of that eagle is now on display at the Museo de la Ciudad, or City Museum, while the eagle’s head made its way to what is now U.S. Embassy Havana, just down the street.

Flagpoles across from the U.S. Embassy. Photo by Brian Canelles.

More noticeable than the U.S. Embassy building are the 138 flagpoles across from it. The Cuban government erected them in 2006 to obscure an electronic billboard that, for a time, displayed pro-democracy messages from the U.S. to the Cuban people.

Continue on to the Necrópolis Cristóbal Colón, where monuments, gravestones, and mausoleums provide windows into Cuba’s history, values, and enduring faith.

Gravesite of Señora Amelia Goyri. Photos by Brian Canelles.

The most carefully tended to and frequently visited gravesite is that of Señora Amelia Goyri, known to the faithful as La Milagrosa, or the Miraculous One.

Goyri died in childbirth in 1901, and her baby did not survive. The mother and child were buried together with the baby at her feet, as was the custom. According to the faithful, when her body was exhumed several years later, it had not decomposed, which is a sign of holiness in the Catholic faith. And the child, they say, was no longer at its mother’s feet but in her arms.

Today, people struggling to have children of their own travel from near and far to leave their petitions at La Milagrosa’s gravesite.

American Legion communal grave. Photo by Brian Canelles.

Spend some time wandering around the massive cemetery — on foot or in a coco taxi. Among several monuments to Americans is the communal grave of the American Legion, the final resting place for dozens of U.S. soldiers who died in the 1898 Spanish-American War.

Visit with local Cubans as you head toward Plaza de la Catedral in the heart of Habana Vieja. Colectivos run along every main drag in Havana and stand in for the lack of public transportation. You never know who you’ll come across and what story they’ll tell.

The couple below, for example, were childhood sweethearts who had just reunited after not seeing each other for more than 13 years.

Left: Couple reunites after 13 years; Right: Street musician performs in Plaza de la Catedral. Photos by Brian Canelles.

Plaza de la Catedral frames the eighteenth century Cathedral of Havana, considered one of the finest examples of Baroque architecture in Cuba. Its surrounding streets are filled with meticulously restored buildings, and are magnets for street musicians and vendors catering to tourists.

Left: Photo by Geoffrey Baer; Center/Right: Photos by Brian Canelles.

If you’re in need of refreshment, stop by popular Paladar Doña Eutimia for classic Cuban fare as well as new takes on old classics, including frozen mojitos. Doña Eutimia’s is one of a growing number of paladares, or small, privately owned restaurants that have opened since the legalization of private businesses in the ’90s and the more recent easing of restrictions.

Next to Dona Eutimia’s is the Taller Experimental de la Gráfica, a workshop where young artists learn the Cuban art of lithography. Originally developed in the nineteenth century in order to create intricate labels and boxes for cigars, lithography has developed over time into a popular multimedia art form.

Photo courtesy of Doug Kaye / Flickr.

This particular workshop has an interesting history. The number of skilled lithographers in Cuba dwindled in the early twentieth century, following the mechanization of cigar ring and box manufacturing. However, soon after the revolution, a group of young artists petitioned the government to help them acquire several old presses from France, open a studio and track down the old masters. They found one elder lithographer working as a fisherman, and he was able to pass down his techniques. Today, visitors can wander into the Taller Experimental to see local artists in action or to purchase their work in the small shop towards the front of the building.

You’ll likely hear very different opinions of Castro’s revolution depending on whom you ask. But at the Museo de la Revolución, or Museum of the Revolution, there is only one perspective: that of the regime. While a visit used to be required for all Havana schoolchildren, today it caters mostly to curious foreigners, many of whom wear red bandanas or berets to show their solidarity.

The museum is housed in Cuba’s spectacular former presidential palace, constructed in the 1910s and decorated by Tiffany Studios of New York. It was last inhabited by Fulgencio Batista, who was ousted by revolutionary forces.

Museo de la Revolución; Left: Photo courtesy of Simon / Flickr; Right: Photo courtesy of Chris Brown / Flickr.

The strained relationship between the U.S. and Cuba looms large in the museum. Outside the building sits a SAU-100 Stalin tank used by Cuba to fend off the CIA-backed invaders at the Bay of Pigs in 1961. Several dioramas inside the museum recount the sequence of events that led the revolutionary forces to victory during that battle. On the ground floor is the Rincon de los Cretinos, or Cretins’ Corner, where giant cartoon paintings depict enemies of the Castro regime — including former U.S. presidents Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush.

Other exhibits lambast enemies of the revolution, including Batista, and tout the revolution’s accomplishments in the fields of health care and literacy.

No trip to Cuba is complete without tasting a fine cigar, and the array of options can be overwhelming. So after your history lesson, stop at Casa Abel, where proprietor Abel Expósito Diaz, one of the Cuba’s most renowned cigar experts, can guide you through the finer points of tasting, pairing, and indulging in Cuban tobacco.

Left: Casa Abel storefront; Right: Cigars at Casa Abel. Photos by Brian Canelles.

Visit with Don Abel in his smoking room, filled with the kind of plush leather couches that beckon visitors to sit and stay awhile. His giant, walk-in humidor lines an entire wall with neatly stacked cigars. Don Abel has cigar smoking down to a science; he can tell you which cigar to smoke depending on your level of familiarity, what you’re eating or drinking, and the time of day.

Entrance to Paladar La Guarida. Photo by Brian Canelles.

Before sunset, head to the recently opened rooftop piano bar at Paladar La Guarida to enjoy another signature Cuban offering — music. The bar sits atop the ruins of a 1913 palace and offers an unparalleled view of the city, in all of its faded glory. With luck, you might catch Roberto Fonseca, one of Cuba’s most renowned contemporary musicians and one of Geoffrey Baer’s tour guides in the Weekend in Havana documentary. He often performs here when he’s in town.

Most rooftops in Havana have been transformed into ad hoc living rooms, due to both the heat and the lack of space. You might see locals hanging laundry, playing dominoes, or even dancing across the landscape.

Paladar La Guarida rooftop. Photo by Brian Canelles.

La Guarida is one of the first and most famous paladares in Havana, and is popular among international celebrities as well as Cuba’s emerging elite. Like most privately owned restaurants, the inspired menu is constantly changing depending on the availability of ingredients. One common offering is the creamy tres leches cake, filled with a dollop of rich chocolate mousse and lightly dusted with cinnamon.

After dinner, head to Fábrica de Arte Cubano, a labyrinth of bars, galleries, and performance spaces. Sitting in a former cooking oil factory, this arts collective is the epicenter of the new Cuban cool.

Fábrica de Arte Cubano. Photos by Brian Canelles.

On any given night, visitors might be treated to photography, sculpture and painting exhibitions, live music, and maybe even a fashion show, all under one roof. Featured artists and musicians are approachable and often found mingling with the crowd or chatting over cocktails on the patio behind the galleries.

Next to La Fábrica is El Cocinero, another private restaurant that opened in 2013. The selection of creative cocktails, many with juices and syrups crafted by El Cocinero’s expert mixologists, make it the perfect spot for a nightcap or a midnight snack.

El Cocinero. Photos by Brian Canelles.

Day 3

Start your day with a stroll around Parque Central, a central hub for Havana commuters where you can pick up a copy of Granma, the official state-controlled newspaper.

Parque Central. Photos by Brian Canelles.

During baseball season, you’ll find men gathered in the middle of the park passionately debating about Cuba’s national pastime. The spot is known as “esquina caliente,” which literally means ‘hot corner,’ but is Cuban slang for third base.

The love of baseball has linked Cuba and the U.S. since the Spanish-American War, when an allegiance to the sport was seen as an act of rebellion against the Spanish imperialists and a show of solidarity with the Americans.

Across the street from Parque Central is the Capitolio. Designed by a Cuban architect trained in the United States, it closely resembles the U.S. Capitol building but with one important distinction which just about any Cuban will readily point out: the Cuban version is 12 feet taller.

Capitolio. Photo by Brian Canelles.

Though the Capitolio has been slowly decaying since the Cuban Congress was abolished following the revolution, restoration work is now underway.

Hop in one of the beautifully restored antique cars that converge along the edges of Parque Central and head to Havana’s oldest building, the Castillo de la Real Fuerza, built in 1558.

The lookout is accessible to visitors and is topped with a tiny statue of La Giraldilla, the symbol of Havana. La Giraldilla is a tribute to Doña Isabel de Bobadilla, the wife of Cuban Governor Hernando de Soto. De Soto traveled to Florida under orders from the king of Spain to search for, among other things, the mythical fountain of youth. Cubans say that she waited for him in this lookout tower for years, her eyes fixed on the horizon. De Soto died near the Mississippi River and never returned. Isabel, it is said, died of a broken heart. She lives on as a symbol of love, loyalty, and hope that figures prominently in Cuban lore.

Left: Castillo de la Real Fuerza exterior. Photo courtesy of Peter Q; Right: Castillo interior Photo by Brian Canelles.

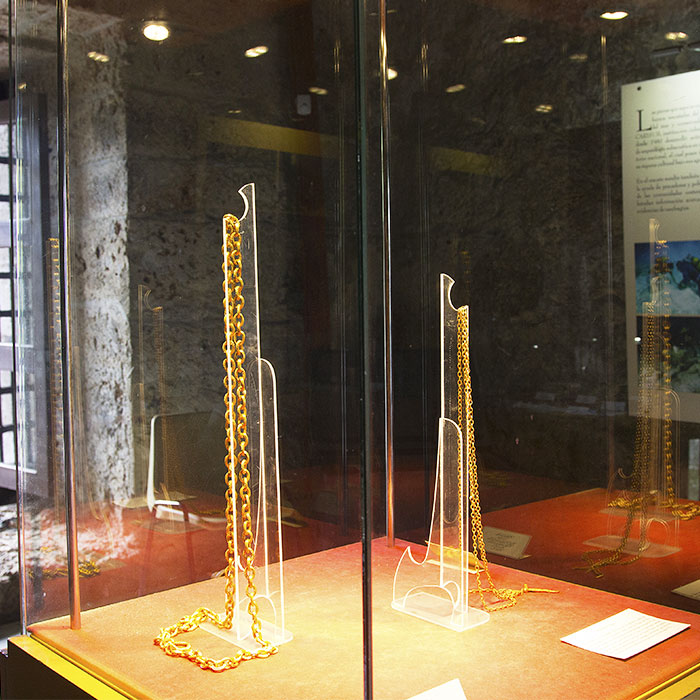

Today, the interior of the fort holds an art gallery, a maritime museum, and treasures recovered from several pirate and merchant ships discovered over the past century in or near Havana Harbor.

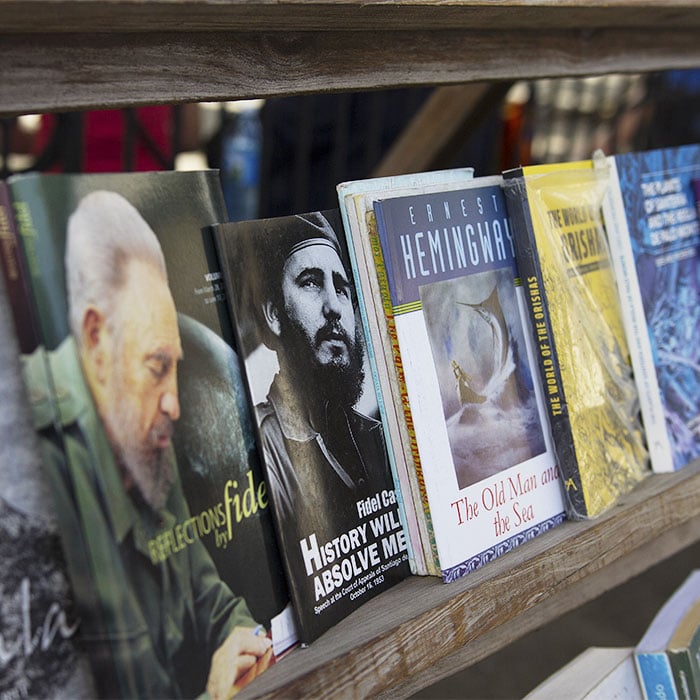

Adjacent to the Castillo is the Plaza de Armas, home to a small flea market where vendors sell antique coins, jewelry, artwork, and books. Several street musicians have also taken up residence along various sections of the plaza, where they compete for tourists’ attention and, of course, their tips.

Vendor wares at the Plaza de Armas. Photos by Brian Canelles.

Ceiba tree at Plaza de Armas. Photo by Brian Canelles.

The plaza marks the site of Cuba’s first public Catholic mass, which took place on November 16, 1519. The exact location is now marked by a ceiba tree, which has stood on the site continuously for nearly 500 years. A new sapling is planted each time an old tree dies. The ceiba tree is also very important to the large number of Cubans who practice the Afro-Cuban religion of Regla de Ochá, also known as Santería.

Take a break from the city and bring your reading material to Santa María del Mar, one of several beaches on the outskirts of Havana.

Finca Vigía. Photo courtesy of The Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

After the beach, stop at Finca Vigía, where Ernest Hemingway lived for the last 21 years of his life. He spent much time on the water near Havana and wrote several novels at Finca Vigía, including The Old Man and the Sea.

“In Cuba he’s considered a native son,” says Cuban-American writer Hugo Perez. “They consider him not an American writer but a Cuban writer. And I think he kind of considered himself a Cuban writer, as well.”

His home has been preserved to appear just as he left it.

Malecón sunset. Photo courtesy of Howard Ignatius / Flickr.

Come back to Havana in time to catch the sun setting on the Malecón. Flamenco dancer Irene Rodríguez says that the Malecón is “like Habaneros’ living room,” where they can escape the heat of their apartments and relax. It is a place where musicians come to play, friends come to sip rum and couples come to swoon by the sea.

“Cubans who live out of Cuba really miss the Malecón,” said Rodriguez.

The Malecón also faces the U.S. and is where many people pushed off for Florida in the ’90s. In August 1994, thousands of people spontaneously descended along the Malecón, responding to rumors that boats would soon be arriving to ferry refugees to the U.S. Though the boats never arrived, a mass exodus ensued, and in a few short months more than 35,000 Cubans fled Cuba in ramshackle ships, headed for the Florida coast.

After three days of indulging in Cuba’s rich art, music, and dance, there’s only one show that can possibly continue to impress: the Cabaret Tropicana. On your last night in Havana, transport yourself back in time with a visit to this high-octane Cuban institution.

Cabaret Tropicana. Photo by Brian Canelles.

Cabaret Tropicana performer. Photo by Brian Canelles.

Founded in 1939, this open-air nightclub was a prime destination for Americans in pre-revolutionary Cuba. Its style of cabaret, later imitated in Las Vegas and across Europe, has changed little in the past 78 years with one exception: today, its showgirls, like most Cubans, are government employees.

Everything about the Tropicana is exuberantly over-the-top. It’s a place where, after a short while, a three-foot-high headdress will begin to appear understated.

The performance is energetic and quick, but it isn’t lacking in substance. The no-holds-barred historical revue highlights key moments in Cuban history and doesn’t shy away from difficult subjects, including Cuba’s long history of slavery.

Cabaret Tropicana. Photo by Brian Canelles.

Day 4

Take one last stroll along the Malecón, this time in the morning light and in the company of fishermen.

Then head to Plaza del Cristo for coffee and coquitos acaramelados — deliciously sweet little coconut balls sold by street vendors. Stop at Café El Dandy for a quick breakfast or light lunch.

Left/center: Plaza del Cristo coquitos acaramelados; Right: Café El Dandy. Photos by Brian Canelles.

Around the corner from El Dandy is the decidedly different souvenir shop Clandestina. Created by Cuban designer and entrepreneur Idania del Río and her Spanish partner, Leire Fernández, Clandestina is an example of Cuban ingenuity, creativity, and ambition. All of the materials used to make their clothes, bags, and other products are upcycled — bought or found in Cuba and turned into something new and one-of-a-kind. Their Vintrash line, in particular, uses discarded American t-shirts as the basis for its screen prints, offering a crafty, cheeky alternative to the classic souvenir tee, with such statements as “This is my Cuba t-shirt” or “Actually I'm in Havana.”

Clandestina shop. Photos by Brian Canelles.

Del Rio says the latter has a dual meaning: it is a nod to her Cuban friends who live elsewhere but whose hearts are still in Havana, as well as a celebration of “those who come for the first time, to make a statement of where they are…[and] feel the power of coming to Cuba right now, at a time so incredible in terms of changes and advances.”

Continue exploring the Cuba’s tastes, sights and sounds. See how Cuba’s historical buildings are being preserved, learn about its long relationship with the U.S. is changing and its economy is transforming, throughout this site.