Geoffrey Baer Explores Chicago's Beautiful School Architecture

Geoffrey Baer

December 20, 2023

School buildings are some of the most important pieces of architecture in our lives. They need to safely and comfortably house children and the variety of spaces required for their development, enabling and encouraging rather than inhibiting education. They are often centers of a community, one of the most prominent buildings you might find in a neighborhood. In a secular world, they are perhaps the most architecturally significant building many people encounter in their everyday lives – every community needs one, after all. In a city of neighborhoods like Chicago, they are often the largest building in a cluster of residential blocks.

There are plenty of beautiful schools to be found in the Chicago area, from the grand edifices of the nineteenth century to modernist masterpieces to zero-energy ingenuities. I’ve already highlighted the architecture of Chicago’s college campuses; now here are some noteworthy grade and high schools, arranged from oldest to newest.

For in-depth histories of many more Chicago Public School buildings, check out the website Chicago Historic Schools, which was put together by a team including the historian Julia S. Bachrach, who appears in my new special The Most Beautiful Places in Chicago 2.

St. Ignatius College Prep

The oldest school building on this list, this Jesuit high school on the Near West Side from 1869 predates the Great Chicago Fire. Designed in dignified, French-influenced Second Empire style by Toussaint Menard, it features a mansard roof and a five-by-five symmetry: five stories of windows and five vertical sections to its front facade. The elegant wood cabinets and balconies of the Brunswick Room look more like a chamber in an archetypal university than a high school.

St. Ignatius is also architecturally significant because it is home to fragments of demolished buildings from throughout Chicago, including the Chicago Stadium and Stock Exchange Building. They’re on the grounds thanks to alumnus Richard H. Driehaus, a late champion of classical architecture who also contributed money to the school’s preservation and expansion.

William H. Ray Elementary School

Originally opened as Hyde Park High School in 1894 to accommodate a neighborhood population that was growing thanks to the World’s Columbian Exposition, this building was Chicago’s largest public high school at the time. But it was quickly outgrown, and became an elementary school in 1914.

It was designed by the Chicago Board of Education’s architect at the time, John J. Flanders, who favored brick Queen Anne-style buildings with overhanging eaves, ornament, and bay windows. (The latter are noticeably octagonal on Ray Elementary.) Flanders designed more than 50 projects for the Board of Education between 1884 and 1893; this building was his last.

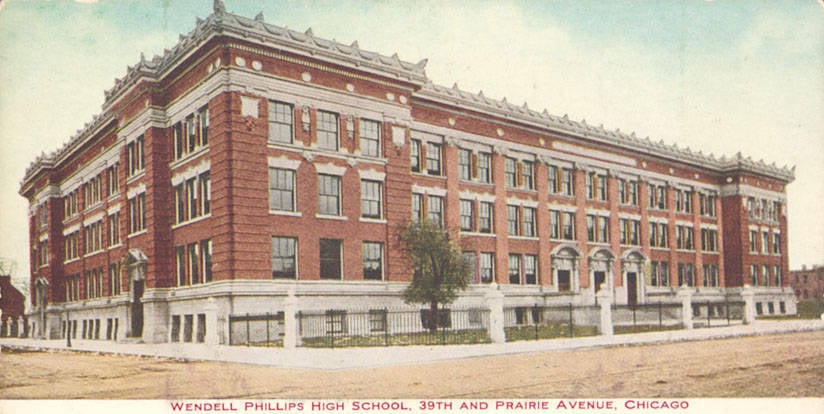

Wendell Phillips High School

Wendell Phillips High School has been an important institution in the Black metropolis of Bronzeville for a century, producing such alumni as Nat King Cole, Sam Cooke, the publisher John H. Johnson, the historian Timuel Black, and the original Harlem Globetrotters.

Named after an abolitionist, it was designed by Chicago Board of Education architect William Bryce Mundie and opened in 1904. Wendell Phillips High School is located in Bronzeville and became Chicago’s first predominantly Black high school within a couple decades. It is in an impressive Neo-Classical style with ornamental columns and other stone decoration. Like many Chicago Public Schools of the time, it was quickly outgrown. Board of Education architect John C. Christensen designed an extension in the 1930s, matching the style of Mundie’s design, as was typical for Board of Education architects when adding on to an existing structure – which they did frequently.

Oak Park and River Forest High School

This high school brought together not just two western suburbs but also two architects: Robert C. Spencer, a resident of River Forest, and Normand S. Patton, a resident of Oak Park. Patton was a Chicago Board of Education architect for two years, and had two decades under his belt of designing school buildings when he took on OPRF in the early twentieth century. The Italianate look of his and Spencer’s 1906 building recalls his Jirka School (now Pilsen Community Academy), just as the imposing red brick fortress of his Lake View High School calls to mind his Armour Institute, visible from the Dan Ryan. The AIA Guide to Chicago discerns a “Prairie spirit” in the original OPRF building, which is now just one of a whole campus of additions from over the decades.

OPRF was the subject of a ten-part series by documentarian Steve James called America to Me. Notable alumni include Ernest Hemingway, Illinois governor Otto Kerner, Jr., and Kathy Griffin.

Carl Schurz and James H. Bowen High Schools

The Chicago Architecture Center says that onetime Chicago Board of Education architect Dwight Perkins “designed some of the most modern and innovative public schools in the country.” He incorporated such reforms as widened stairwells and hallways, bathrooms on every floor, maximal natural light, and open space around schools. He also brought the burgeoning Prairie Style of Frank Lloyd Wright from the home to an institutional building like a school, emphasizing geometries and eschewing fancy ornamentation in favor of warm brickwork. His Carl Schurz High School and James H. Bowen High School are twins both built in 1910, and yet Schurz, in Irving Park, was landmarked by the city in the late 1970s, while Bowen, in South Chicago, wasn’t. That’s exemplary of the way architecture on the South Side has been overlooked, architecture critic Lee Bey told us in The Most Beautiful Places in Chicago 2.

Albert G. Lane Technical High School

A school meant to provide technical training is also chock-full of art. The original Lane Tech building was designed by Dwight Perkins and opened in 1908 in Old Town, but was quickly outgrown. Chicago Board of Education architect Paul Gerhardt, Sr. drew up a plan for a new school at the current location at Addison St. and Western Ave. in the late 1920s, but his Board of Education successor John C. Christensen oversaw the final phases of construction, which were delayed by the Great Depression, and the school opened in 1934. It’s a massive Tudor Gothic building with a noble clock tower and an interior courtyard. Artwork largely funded by New Deal programs can be found throughout the school, including murals moved to the school from the 1933 Century of Progress World’s Fair, a painted fire curtain in the auditorium, frescoes, and sculptures. A neighboring concrete stadium by Christensen was also funded by the federal Works Progress Administration.

Chicago Vocational Career Academy

Like Lane Tech, Chicago Vocational Career Academy in Avalon Park opened in 1941 to train students in technical skills. Also like Lane, the John C. Christensen-designed building is enormous, occupying 27 acres. It is in a monumental Art Moderne style reminiscent of government buildings of the era, with massive columns, bas-relief panels depicting the trades taught inside, and impressive use of limestone. It, too, was built in part with funds from the New Deal. Architecture critic Lee Bey is an alum, and showed me the school in The Most Beautiful Places in Chicago 2.

Crow Island School

This school largely defined how schools in the postwar era were designed. Winnetka superintendent of schools Carleton Wolsey Washburne wanted an open, child-focused school, while architect Lawrence Perkins – the son of Dwight Perkins – wanted to design an innovative school. Washburne was skeptical of Perkins and his partners’ inexperience, so they brought in the respected father-son team of Eliel and Eero Saarinen to join them.

The architects surveyed teachers and incorporated their thoughts into their design, which was modern and low, unlike the monumental school buildings of earlier decades. The modern design prioritizes light and the outdoors (just as Perkins’ father did in his designs) by extending classrooms off a hallway so that they have three walls of windows. Eero Saarinen designed furniture suited for the students, while his fianceé Lilian Swann designed decorative tiles depicting animals to stud the brick exterior. Eliel’s wife Loja designed curtains and textiles for the interior. The influential school opened in 1940.

Lawrence Perkins’ firm, now known as Perkins+Will, has gone on to design hundreds of schools, continuing to prioritize transparency in modern designs in buildings like the midcentury Whitney M. Young Magnet High School and Walt Disney Magnet School.

Josephinum Academy of the Sacred Heart

This midcentury modern school in Wicker Park has some intriguing details that distinguish it from the standard school design of the era. Designed by Michael Gaul and opened in 1959. While the glass blocks set above horizontal bands of clear windows and a mix of brick and concrete are typical, it also incorporates innovative elements like a dramatic patterned screen of hollow concrete blocks in front of the library and a surprising wall of glass blocks that opens the gymnasium up to outdoor light.

The land on which it sits was put up for sale earlier this year, but the school hoped to buy the property itself and remain in place.

Anthony Overton Elementary School

A “superb example of midcentury modern architecture,” according to architecture critic Lee Bey, this Bronzeville school opened in 1963 and was designed by Perkins+Will, the same firm behind Crow Island. As at that suburban school, natural light is abundant thanks to glass corners and glass hallways, while yellow and teal brick brighten the exterior.

Overton, Beethoven, and Admiral Byrd schools were all designed in a similar style to serve nearby high-rise public housing projects, and as a contrast to them: low-rise, bright, open. Beethoven is the only one still operating as a school. Admiral Byrd has been demolished, and Overton was one of 49 Chicago public schools closed in 2013 in the largest school closure in the history of the United States. Most of the closed schools, like Overton, were on the historically disinvested, predominantly Black and Latino South and West Sides.

While a number of the closed school buildings have been sold and repurposed – including the only three North Side schools shuttered in 2013 – Overton remains empty. But designers and activists have used its campus for large-scale art pieces and “activations,” including a huge map of the city that highlights disparities.

Cesar Chávez Multicultural Academic Center

The bright colors and shapes of this building look like a child’s building blocks, and perfectly encapsulate a simple philosophy: that learning can be fun. Carol Ross Barney enlivened the 1993 Back of the Yards school with all sorts of simple yet delightful effects. A cube-shaped library breaks the long line of the school and is topped with a pyramid-shaped skylight echoed by triangular windows protruding at ground level. Squares of blue brick add further life to the library, while yellow triangles elsewhere on the school echo the library’s windows.

Such joyful shapes and hues also distinguish Ross Barney’s 1996 Little Village Academy, whose box shape is punctuated with geometric protrusions, including a semi-circular, glassy tower that contains an enormous sundial.

José Clemente Orozco Community Academy

Colorful mosaic mural panels run above the second floor windows of this low-slung building – fitting ornament for a school named after a Mexican muralist. The school was designed by Alphonse Guajardo and Urbanworks and opened in 2000 in Pilsen, a neighborhood with a strong Mexican presence. The murals, many of which feature Mexican and Mexican American subjects, were drawn by students under the supervision of art teacher Francisco Mendoza and then digitized and turned into mosaics.

Jovita Idár Elementary and Victoria Soto High School, Acero Schools

The UNO charter school group held a competition for an elementary school design, and chose the submission from the architecture firm of JGMA. The school opened in 2011 in Gage Park. The futuristic look and dynamic shape of the building anticipate JGMA’s university building called El Centro, which hugs the Kennedy and was featured in The Most Beautiful Places in Chicago.

Victoria Soto High School opened two years later on the same campus with a design by Wight & Co. It’s a glassy circle broken up by a slash of bright red paneling around the entrance.The center of the circle contains a protected courtyard. Idár and Soto are “two of the most architecturally dynamic school buildings in the city,” architecture critic Lee Bey has written, turning a former industrial site into an engaging school ground.

Bernard Zell Anshe Emet Day School Expansion

It’s not often you find a building inspired by a garment, but this is one. The irregular vertical bands of windows interrupting the masonry facade are inspired by a tallit, or traditional Jewish fringed prayer shawl. That element of the building hovers over an open ground floor surrounded by glass, which includes a unique sacred space enclosed by twelve curved brick walls in a pinwheel shape. Wheeler Kearns designed the striking 2019 addition to this Jewish school in Lakeview.

Amongst the alumni are former mayor Rahm Emanuel, NPR’s Scott Simon, and the comedian Ike Barinholtz.