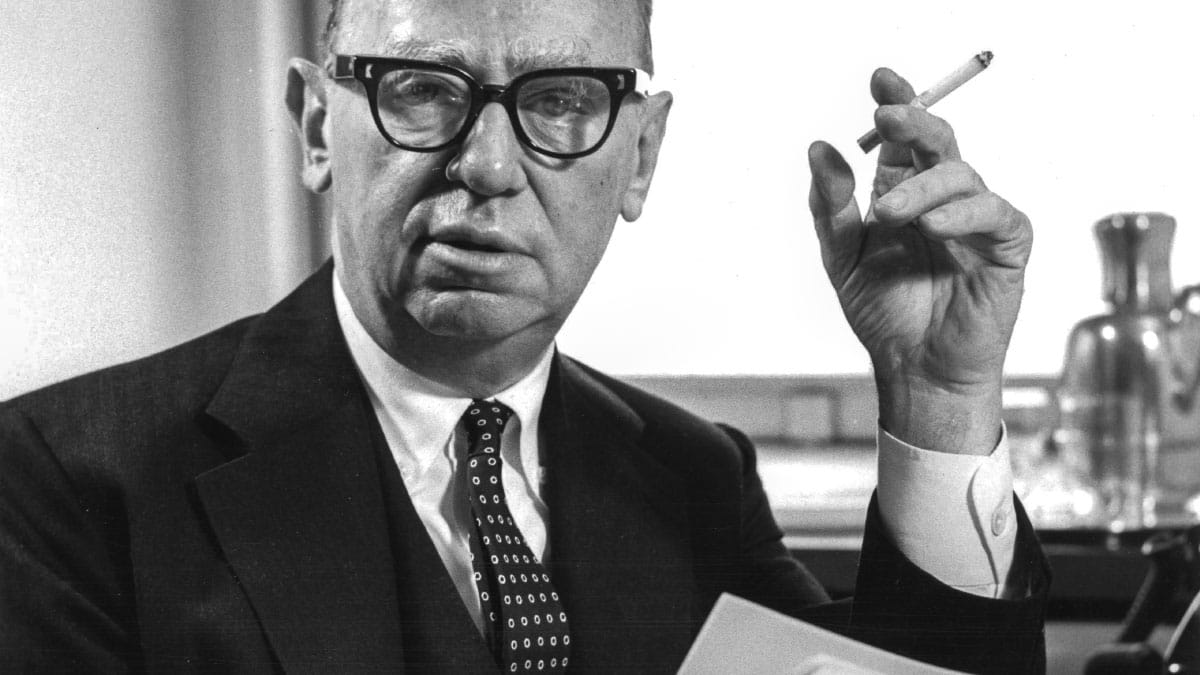

Look at every corner of Chicago today – the iconic skyline, the public art, the sprawling airport, the expansive expressway system – and you can find remnants of Mayor Richard J. Daley’s legacy. While he served as the city’s mayor for six terms between 1955 and 1976, Daley enacted policies that shaped the city’s landscape. As the powerful boss of the city’s Democratic Party, Daley wielded his machine with the help of patronage politics, and he got a lot accomplished in the process. Daley molded the city’s downtown and its neighborhoods to fit his vision of a more modern Chicago. But even as parts of the city flourished, not every Chicagoan and not every community were included in that vision.

The Boss

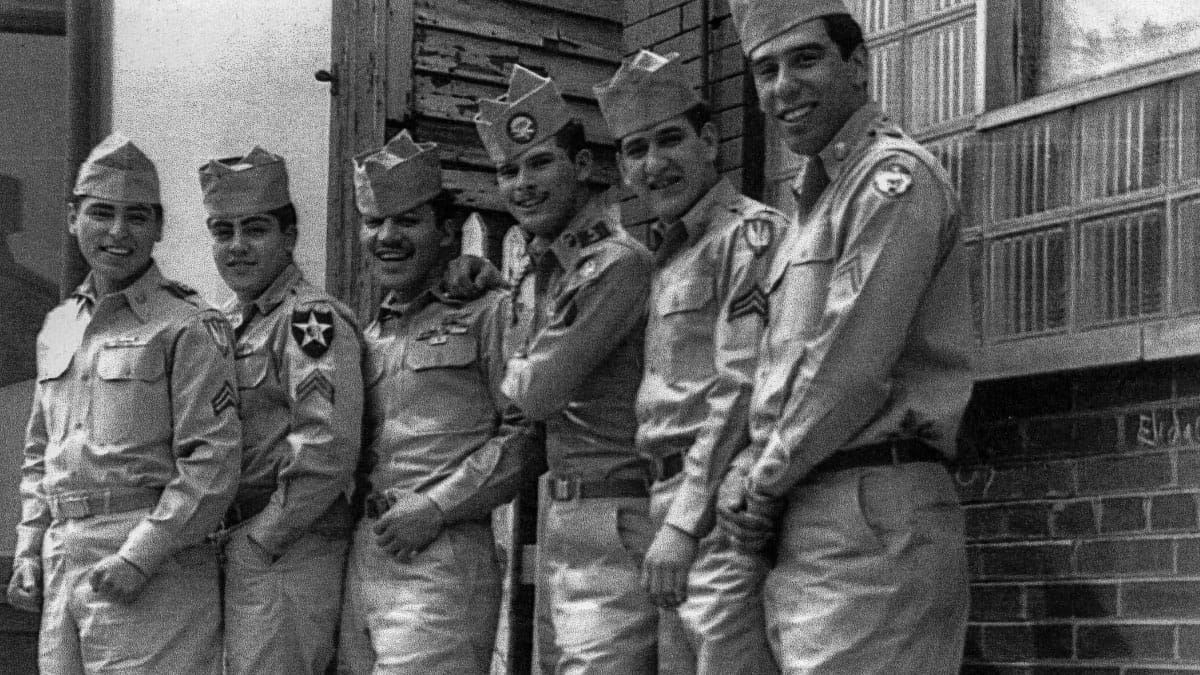

An only child and the descendant of Irish immigrants, Richard J. Daley was one of five Chicago mayors that came from Bridgeport, a Southwest Side neighborhood that was predominantly Irish during Daley’s life. Daley worked his way up through city and state politics. He worked as a precinct captain, served in both the Illinois House and Senate, and held various city positions before becoming chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party in 1953. That put him in a position of power in the city and in the Democratic machine, where he oversaw the city’s 50 wards, precinct captains, and thousands of patronage jobs. In patronage politics, wards were given an allotment of jobs in exchange for loyalty to the city’s Democratic organization.

“This system gave the party several resources: the ability to raise campaign money, an energetic army of campaign precinct workers, and enormous power over the selection and election of candidates,” writes David Orr, former Cook County Clerk and himself briefly acting mayor of Chicago, for the Chicago History Museum's Encyclopedia of Chicago.

Not long after becoming party chairman, Daley ran for mayor against incumbent Martin Kennelly and won. As mayor and leader of the party, Daley was thoroughly in charge. He would serve six terms as mayor. In his 1955 inaugural address, Daley laid out one of his main goals, which was to make “our neighborhoods and our city a better place in which to live.”

As Daley was taking office, American cities across the country were seeing their populations decline as residents – most often White – moved to the suburbs in droves. To combat this, cities such as Chicago implemented urban renewal: public programs that sought to revitalize inner cities by clearing slums and eliminating blight.

“There are no isolated communities in the city. Blight is not a threat to just one area. It is a threat to all our neighborhoods. All of us, wherever we live, have a stake in the renewal and in the conservation of the city,” Daley said in another address.

But some neighborhoods, particularly Black and Latino communities, bore the brunt of these policies. Eminent domain, which enabled cities to seize private property for public use, was a common tool for carrying out urban renewal policies. As a result, some residents were displaced by urban renewal projects.

During Daley’s tenure, Chicago became “the city that works.” The city improved its sanitation, grew the police and fire departments, built expressways, installed public art, expanded O’Hare, and built new high-rise buildings. Some of these projects left an indelible mark on the city and its residents and reveal how the boss and his bulldozer shaped the landscape of Chicago.

Robert Taylor Homes

As mayor, Daley oversaw the construction of massive public housing projects, including the expansion of the Cabrini Green homes, Stateway Gardens, and at one time the largest public housing complex in the country: the Robert Taylor Homes.

By the mid-20th century, Chicago’s Black population was growing rapidly, in part because of the Great Migration, which saw Black migrants from the South settle along the city’s “Black Belt” on the South Side. But as some of the city’s Black neighborhoods grew and became overcrowded, the city faced a dilemma.

“One of the really important themes, I think, that Daley had to deal with was this racial tension – a huge and growing Black population running out of space. And where are they going to go?” Roger Biles, professor emeritus of history at Illinois State University, told Chicago Stories. “The neighboring White population said, ‘Well, you’re not coming here.’”

A stretch of Federal Street considered “slums” on the South Side was the manifestation of this issue.

“As the Black Metropolis is thriving, outsiders are looking at it as a ghetto, as a slum. They look at it as a place with lots of trash or overcrowded,” Mary Patillo, the Harold Washington Professor of Sociology and chair of the Department of African American Studies at Northwestern University, told Chicago Stories. “That overcrowding is completely manufactured by the inability of people to move out because of mob violence or realtor’s pacts not to sell to Black people.”

In 1959, the bulldozers came to Federal Street to make way for a new public housing project. The plan called for 28, 16-story high-rise buildings with roughly 4,300 units that were built along two miles of State Street from 39th to 54th streets. They were named for a Chicago Housing Authority board member and activist named Robert Taylor, who ironically, according to Erik Gellman in the Encyclopedia of Chicago, “resigned when the city council refused to endorse potential building locations that would induce racially integrated housing.”

At the opening of the Robert Taylor Homes in 1962, Daley said, “This project represents the future of a great city. It represents vision. It represents what all of us feel America should be, and that is a decent home for every family.”

They were advertised as sleek and modern, with new appliances and elevators – a notable improvement for some.

“People had been living in really dilapidated conditions, especially poor African Americans…they might not have had good running water,” Patillo said. “The early days of public housing, we have this statement actually: ‘Public housing is paradise.’”

But it fell short of such a promise. Overcrowding became a major issue. The complex was designed to house 11,000 people, but its peak population topped 27,000. It was often in disrepair, with broken elevators and heating and shoddy building codes. The conditions fostered crime, gang violence, and drug use.

What was once the largest public housing site in the country became what is widely considered to be one of the largest failures. The last of the high rises was torn down in 2007. The mayor who oversaw the demolition was Daley’s son, Richard M. Daley.

“What made them a failure wasn’t purely the design…What made them a failure is building them that way and then treating them the same way the city treats the slums they replaced. You starve it out of city resources, of economic opportunity, all those things. The same thing happens to this new housing that happened to the old.”— Lee Bey, architectural critic for the Chicago Sun-Times

According to Biles, Daley was not open to integrated neighborhoods because he said his White constituents opposed it. But as Chicago journalist and author Rick Kogan told Chicago Stories, looking back at the results from the 1963 mayoral election, “Daley did not get the majority of the White vote. Daley was elected on the shoulders of Black Chicago.”

But through redlining, discriminatory housing practices, and public housing, Daley’s policies had confined Black residents to one particular area. The Dan Ryan Expressway, the construction of which Daley, too, had overseen, was just to the west of the Robert Taylor Homes. The expressway “cut off various neighborhoods – forever – from White Chicago,” said Kogan.

“Give them these high-rise buildings and contain them there,” Chicago Tribune columnist Laura Washington told Chicago Stories. “The message got heard all the way on the South Side: ‘We don’t want you downtown.’ The downtown is for the wealthy, the downtown is for the privileged, and the way he expressed that was by putting up all these glorious high-rises and parks and everything else that he did downtown.”

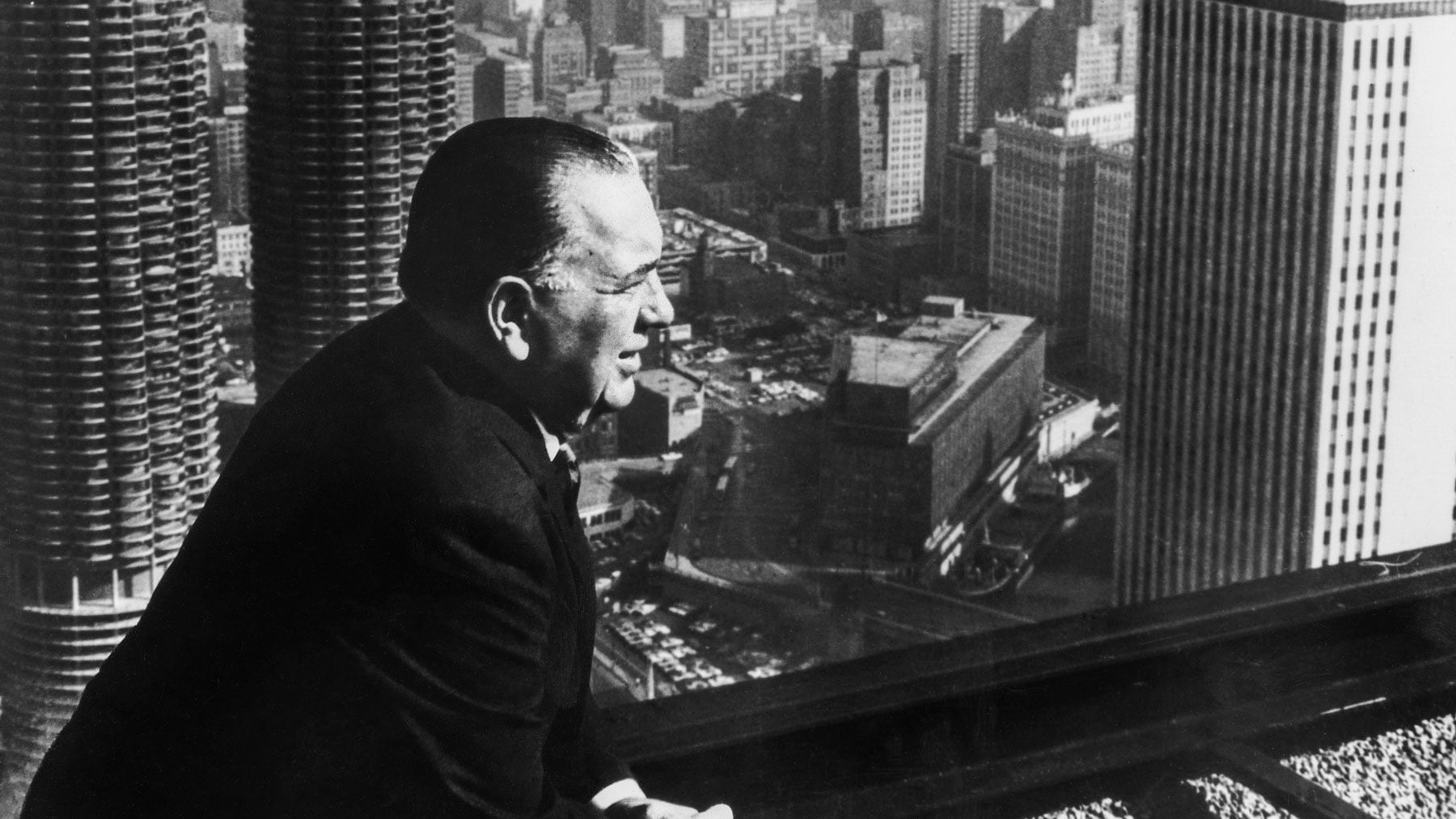

A Bustling City Center

When Daley took office in 1955, the city was coming off a lull in building. The Great Depression and World War II had slowed construction, and few new buildings had gone up. Though the Loop had some busy, thriving, commercial stretches such as State Street, “It was kind of crummy,” Kogan said. “It was dark. It was all brick.”

The city’s new expressways had made it easier for suburban residents to get in and out of the city for work, so Daley wanted to make the city a place where they would want to stay.

“I don’t think Detroit in 1955 realized what it was going to become. I don’t think Cleveland did. I don’t think Buffalo did, too. I think Daley was aware because he was smart. Daley was aware of what a massive exodus of people would mean for this city.”— Rick Kogan, journalist and author

Daley found the solution to the Loop’s problems in new, modern buildings. The embodiment of that was Marina City, a mixed-use development advertised as a “city within a city.” Everything residents needed – right down to a movie theater – was within their own building. Other buildings, such as IBM Plaza (now AMA Plaza), Lake Point Towers, the John Hancock Building, Water Tower Place, and Sears Tower (now Willis) were all built during Daley’s tenure.

As businesses, too, eyed the suburbs, Daley also had an answer for them: McCormick Place. The sprawling convention center opened in 1960 with 23 meeting rooms, a 5,000-seat theater, and a 320,000-square-foot exhibit area (which burned in a 1967 fire and was later rebuilt; McCormick Place would further expand in the decades to come). Daley wanted Chicago to be a place to live and a place to do business.

“It’s reinforcing to the business class especially that Chicago [is] not going the way of some other cities,” Bey said.

Chicago set itself apart with some of its art and design choices, too. Completed in 1965, the Civic Center (now known as Daley Center, named for him just a week after his 1976 death) was built to house the Cook County Circuit Courts.

“It’s hard to see…with contemporary eyes how revolutionary the Daley Center was at the time. Government buildings tended to look like Roman senate buildings [with] columns, very stern and official,” Bey said. “This was modernism and the idea of a government building not being this creaky old thing.”

The building had a clean modern design, floor-to-ceiling windows, elevators and escalators, and was “designed to send a message” to businessmen.

“This is a new downtown. This isn’t the one we used to have back before the war and the depression, and if I can create this building, if I can put this kind of vision together in the middle of downtown to build this Civic Center, then so can you,” Bey said of Daley’s thinking.

A "Colossal Booboo": The Incredible Story of the Chicago Picasso

One of Chicago's most iconic emblems came out of an unlikely alliance between a gruff, conservative mayor and a sensuous, progressive artist. Through the mediation of a charming bon vivant architect, they changed the face of public art in America.

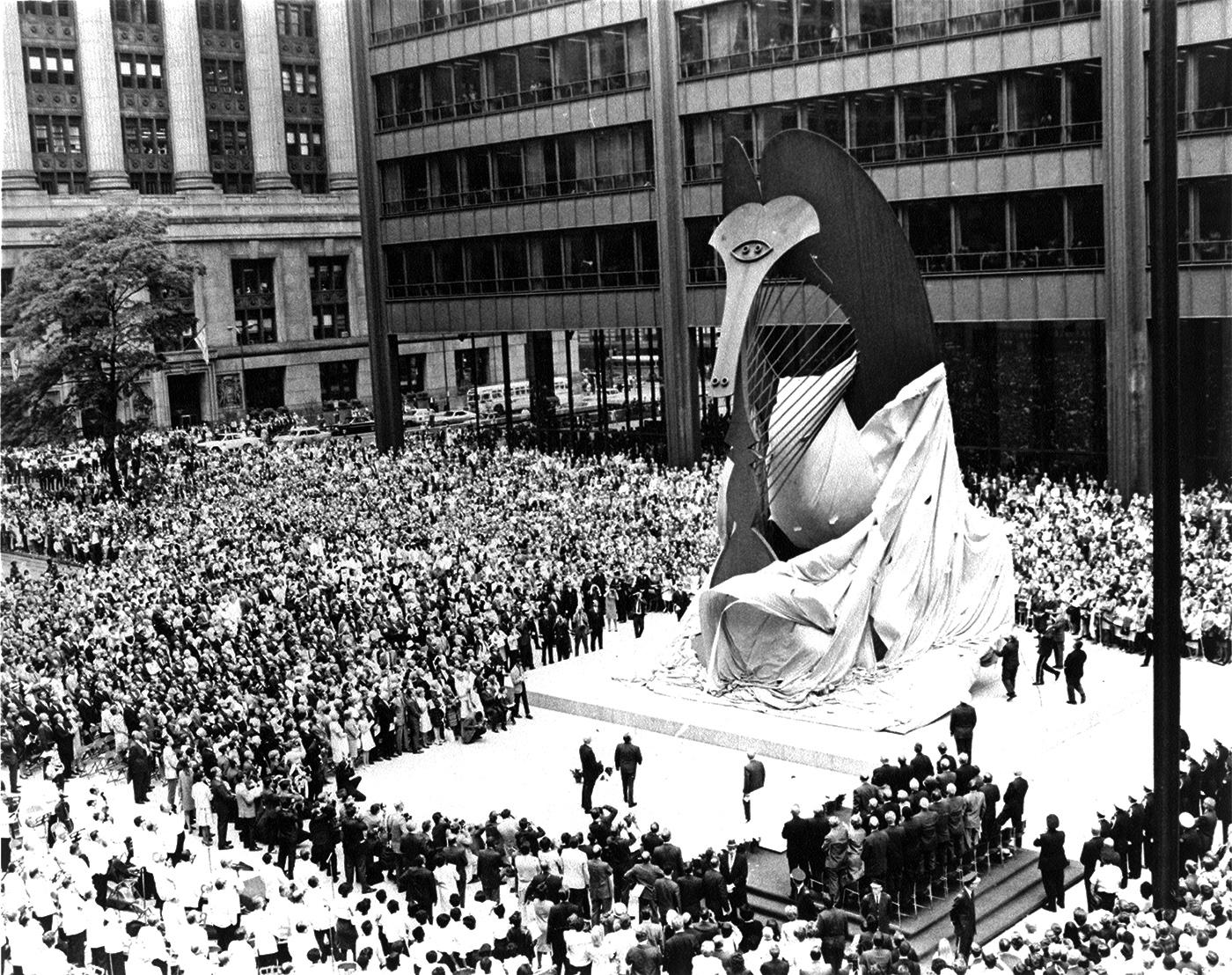

Go deeperThe Picasso sculpture outside the Civic Center also raised some eyebrows. When the sculpture was first revealed to a crowd on August 15, 1967, it was met with mixed reviews, and even more mixed interpretations as to what the sculpture was. Daley reportedly said it looked like the “wings of justice.”

“It creates this interesting thing that happens downtown where you’ve got these government buildings…with an element of art next to it,” said Bey, indicating Flamingo by Alexander Calder at Federal Plaza and Monument with Standing Beast by Jean Dubuffet outside the Thompson Center. “Chicago, once again, was on the cutting edge of that. Daley is thinking about this stuff in the ’50s and ’60s when many places didn't quite get there until the ’70s and ’80s and ’90s.”

The outsized emphasis on downtown, however, meant that all those resources stayed in the city center, too.

“This sort of sounds like trickle-down economics in some ways,” Biles said. “You put all the resources here and then it’s gonna trickle down to the neighborhoods. Well, how much trickles down and how rapidly? … Are they just going to collect the scraps that fall off the table?”

The Construction of UIC and the Demolition of Little Italy

Following World War II, before Daley and his administration reshaped the Near West Side, the University of Illinois had a small campus on Navy Pier. But it served students only for the first two years of study before requiring them to go to Urbana-Champaign to finish their degree. Daley wanted to bring a University of Illinois campus to Chicago.

The city looked at a variety of sites, including Meigs Field, Goose Island, and Garfield Park, but they were all rejected eventually. A location in the South Loop was proposed, too.

“Downtown businessmen were originally enamored of the idea of putting the campus south of the Loop on railroad land that would be a perfect barrier against the Black Belt to the south,” Biles said. “The problem, however, was that those pesky railroads wouldn’t sell the land at what Daley and others considered to be a reasonable price.”

Meanwhile, a few miles away on the Near West Side, residents were working to get their neighborhood designated as a slum clearance site so that they could access federal funds to improve their neighborhood. The community had a growing number of African Americans and Mexican immigrants, but a small, tight-knit community of Italian Americans still called Little Italy home.

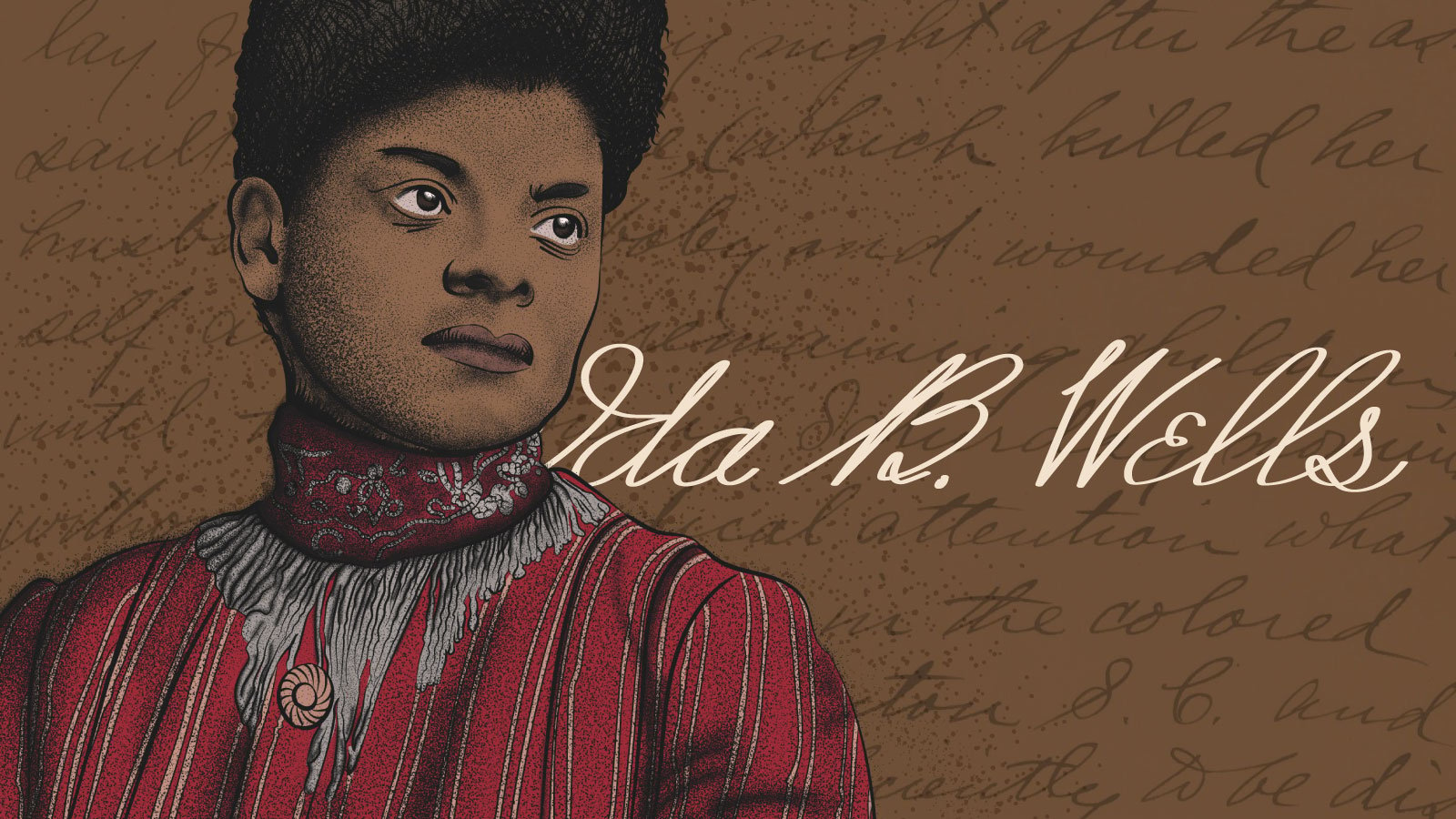

To get their neighborhood to qualify, some residents formed the Near West Side Planning Board. The group’s treasurer and secretary was Florence Scala, who took photos that documented blighted areas in the neighborhood to make the case for the urban renewal funds.

In his 1971 book Boss, columnist Mike Royko describes the neighborhood.

“By the 1960s it was a quieter place and the residents were fighting to keep it alive. The best Italian restaurants, the stores that sold the cheeses and the spices, and the sense of home were there. Much of the property was very old and run down, but the people had reversed the deterioration and the neighborhood was improving.”— Mike Royko, Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago, 1971

According to Steven Giovangelo, Scala’s nephew, most of the neighborhood was made up of working-class homes and businesses that were well maintained.

“Most of the men in the neighborhood all had city jobs. Everything was ‘You look after me, I’ll look after you.’ So the neighborhood was Democrat,” Giovangelo said. In other words, they had supported Daley. The city had assured the neighborhood that urban renewal would be used to bring the neighborhood back to life.

But the city went back on its promise to the neighborhood. Since the city couldn’t settle on a location for the new campus, it finally turned to Little Italy, where some of the demolition had already been done. Construction could move quicker, it was close to downtown, and it was just off the Eisenhower Expressway, making it convenient for commuters. Thanks to Daley’s carefully tuned machine, ward bosses fell in line, and any neighborhood resistance was futile. The city would bulldoze approximately 800 homes and 200 businesses.

“When we would hear references to the area as a slum, it was [resented] because it was not a slum. I can remember old Italian women in the summer getting their broom out and sweeping the sidewalk if guys threw cigarettes on them,” Steven Giovangelo, the nephew of Florence Scala, told Chicago Stories. “It was such a betrayal.”

Florence Scala and 50 other women worked together to stage a sit-in at City Hall, waiting outside Daley’s office to make their point. Despite their efforts, the city prevailed. The University of Illinois at Chicago Circle (today, the University of Illinois Chicago) opened in 1965, and the student body grew rapidly in the first five years. Little Italy, for the most part, no longer exists as it once did.

“You have to admire Florence, and you have to admire anyone who is fighting to keep the character of a neighborhood,” Kogan said. “Once-great neighborhoods have lost…their character – and their characters.”

According to a University of Richmond study, an estimated 22,950 families were displaced by urban renewal projects in Chicago by the late 1960s, 64% of which were families of color. Between 1955 and 1966, 300,000 families were displaced nationwide, and that figure doesn’t include single adults.

“All this comes at a cost,” said Bey. “One that we grapple with even to this day, which is the neighborhoods, particularly the Black and Brown neighborhoods, were not invested in nearly at the rate of downtown.”