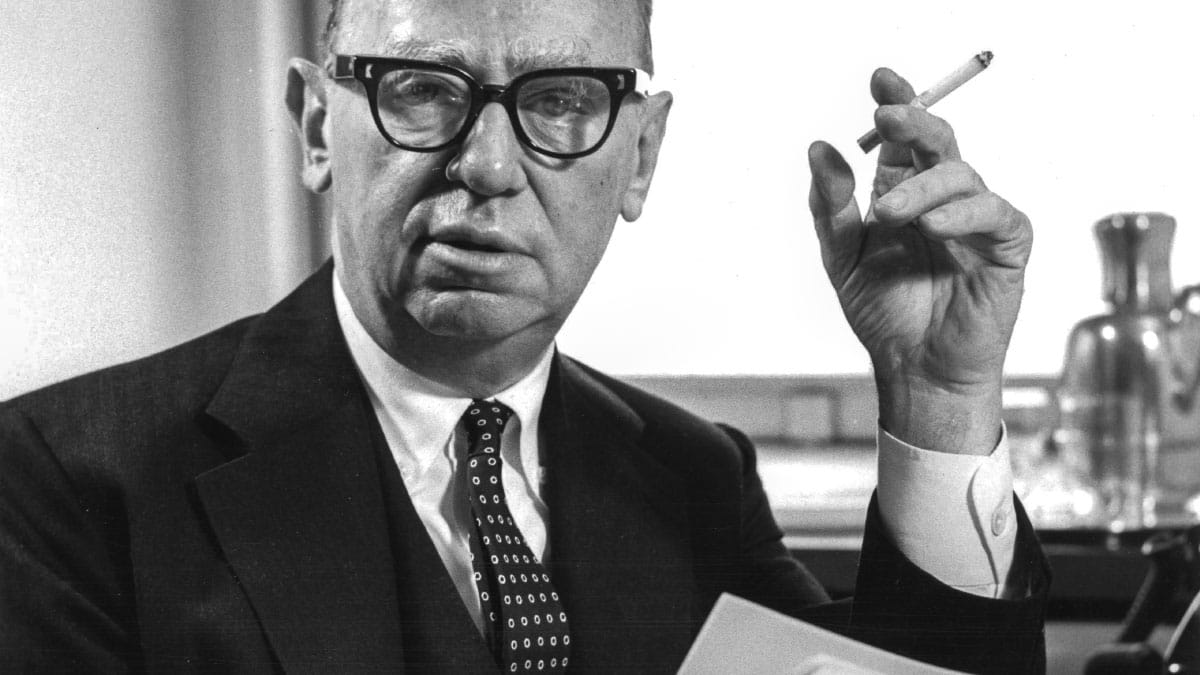

In his 1959 inaugural address, Mayor Richard J. Daley, then entering his second term as mayor, spoke proudly of his urban renewal policies – policies designed, at least in theory if not in reality, to rid the city of blight and redevelop Chicago into a world-class city during a time in which people were moving to the suburbs in droves.

“Although the language of urban renewal speaks of projects, of developments, of planning and capital improvements, of site selection, land acquisition, legislation and financing, we must never forget that the most important work is ‘people.’” Daley said in his address. “The purpose of urban renewal is to serve people better.”

But which people were served better? That’s a question that critics of these policies have asked in the decades since.

There are landmarks around the city of Chicago that were built in part because of Mayor Daley’s policies, some of which remain iconic gems that once breathed a new, modern life into downtown. But other products of Daley’s policies, still intact today, razed entire communities and reinforced or worsened divisions.

Explore some of these landmarks below, with images taken by Chicago photographer Barry Butler.

The Eisenhower Expressway

Construction on the Eisenhower Expressway (pictured here, facing slightly northeast with the University of Illinois Chicago on the right) began before Daley took office, but he was there for the dedication in 1960. Before the expressway was built, the land was part of the Near West Side neighborhood and was home to primarily Black, Jewish, and Greek populations. Once it was complete, the Eisenhower had displaced approximately 13,000 people. Eminent domain – the power of the government to take private property with compensation – made this possible, but it also became a dual-purpose tool for Daley’s urban renewal efforts. With the federal government footing some of the bill, the city could clear slums while simultaneously modernizing the city.

Little Italy, Taylor and Loomis streets

Chicago’s Little Italy neighborhood was one of the battlegrounds for Daley’s plans to reshape the city. In the late-19th and early-20th centuries, Italian immigrants had settled along Taylor Street. Though Mexican immigrants and Black Chicagoans also later settled in this area, it remained home to a small but close-knit Italian community with working class homes and small family businesses. Many of its residents were Democrats who had helped elect Daley. In the 1950s, some of the members of the community worked to get the neighborhood declared a slum clearance site in an effort to secure funds to revitalize the neighborhood. But what began as an attempt to save the neighborhood ended up laying the groundwork to destroy it.

The University of Illinois Chicago

One of Daley’s goals was to have an affordable public university within Chicago. After World War II, the University of Illinois established a campus at Navy Pier, but it wasn’t conveniently located, accommodated students’ first two years of study only, and didn’t award degrees. The university and Daley’s administration looked at various sites, including Meigs Field, Goose Island, and Garfield Park, but they were all rejected. With eminent domain already in place in Little Italy thanks to the community’s efforts to get it designated as a slum clearance site, construction of a new campus on the Near West Side could move quickly, so Daley selected the area for UIC’s new campus. The residents of Little Italy saw this as a betrayal. In the end, some 800 homes and 200 businesses were bulldozed to make way for the new campus, which opened to students in 1965.

1030 West Taylor Street, the Former Home of Florence Scala

This building at 1030 West Taylor Street is the former Little Italy home of Florence Scala, an activist who worked to stop the city from tearing down her neighborhood. Scala, the daughter of an Italian tailor, was a member of the Near West Side Planning Board. She documented blight in her community by taking photographs that would help acquire federal funds to fix up the neighborhood. To try to stop Daley’s administration from moving forward with their UIC campus plans, she staged a sit-in at City Hall with other women from her neighborhood. Though her fight was ultimately unsuccessful, she continued to be a vocal activist, running as an independent candidate for 1st Ward alderman in 1963. There were two attempted bombings of her home on Taylor Street. According to one Chicago Tribune article, the crime was never solved, but a similar bombing happened to a precinct worker who supported Cook County sheriff candidate Richard Ogilvie. Scala also supported the Republican Ogilvie, who was not part of Daley’s Democratic machine.

Chicago’s Growing Skyline

In the mid-20th century, populations in cities across America were shrinking as people, particularly White people, moved to the suburbs. The automobile had made people more mobile, and people no longer needed to live where they worked. When Daley created his vision for Chicago, he had his sights set on downtown. “The mayor was known as a builder. The skyscrapers, the parks, everything that the mayor was doing was about downtown – and that’s White downtown, that’s wealthy downtown,” Laura Washington, a Chicago Tribune columnist, told Chicago Stories. Some of the buildings constructed during Daley’s tenure are still iconic focal points in Chicago’s skyline, including Hancock Tower, AMA Plaza, Marina City, and Willis Tower. Marina City, completed in 1967, is a prime example of Daley’s vision – a mixed-used, “city within a city” development that would provide residents with everything they needed in one complex, such as a theater, bowling alley, and shopping.

But while the Loop transformed, some of the city’s predominantly Black neighborhoods saw the construction of new public housing. Daley turned his attention to the Francis Cabrini Homes in 1957, which were not too far from the Loop. His administration oversaw the construction of new high rises there in an attempt to alleviate overcrowding. On the South Side, a crowded, six-mile stretch of housing was bulldozed in 1959 to make way for the Robert Taylor Homes, which consisted of 28 high-rises that were meant to be modern and new. But critics said these plans only exacerbated existing segregation. “Give them these high-rise buildings and contain them there,” Washington said. “The message got heard all the way on the South Side: ‘We don’t want you downtown.’”

Both the Cabrini-Green high-rises and the Robert Taylor Homes were torn down under Daley’s son, Mayor Richard M. Daley.

The Dan Ryan Expressway

The Dan Ryan Expressway first opened to traffic in 1961, allowing residents to get into the Loop for work and back to their suburban homes with a newfound ease and speed. Today, it is as wide as 14 lanes across. The Dan Ryan, however, reinforced the divide between the primarily Black Bronzeville and the mostly White Bridgeport where Daley grew up. More Black residents were displaced by the construction of the Dan Ryan than White residents. Some of these residents had already been displaced once before when the city used eminent domain to build Stateway Gardens and the Robert Taylor Homes, according to the Chicago History Museum.

The Daley Center and the Picasso Sculpture

Originally known as the Chicago Civic Center, this building was completed in 1965. At the time, it was the tallest building in the city, though Hancock Tower would claim that title four years later. Today, it may appear to be a simple skyscraper, but it was a radical idea for its time. Its modernist design was a departure when compared to other traditional government buildings. The plaza adjacent to the building contains the untitled Picasso sculpture. Though the initial response to the sculpture was decidedly mixed, it, too, represented Daley’s vision of downtown Chicago – an exciting, modern city with public art by world-renowned artists. Though the interpretation of the sculpture is in the eye of the beholder, Daley reportedly said it looked like “the wings of justice.” Just one week after Daley’s death in office in 1976, the city renamed the Chicago Civic Center for the late mayor.