In the mid-to-late 1800s, a relatively new town called Chicago was rapidly growing, but it had a problem. Thanks to polluted waterways and lack of a sewage system, waterborne diseases were running rampant, killing thousands of Chicagoans over the course of a few decades. At the heart of the problem was the Chicago River itself, which carried waste toward the city, not away from it. So city officials came up with a bold plan: what if Chicago reversed its river? In a remarkable feat of engineering, the city did just that, inventing new technologies and angering some downstream neighbors along the way. More than 100 years later, the city can still see and feel some of the effects – both good and bad – of one of Chicago’s biggest undertakings.

When Minnows – and Worse – Came Out of Chicago’s Faucets

Long before kayakers paddled along the Chicago River or diners sipped wine on the Riverwalk or visitors looked up at the dazzling buildings from a tour boat, Chicago was a rugged frontier town, and its waterways were a reflection of that.

After Chicago officially became a town in 1833, the city’s population rapidly expanded. A town of roughly 300 people at its incorporation, Chicago grew to more than 100,000 people by the 1860s and reached 1 million residents by the 1890s. People flocked to the new city for all the opportunities a new city might afford. But with all those people came waste in all its unsavory forms.

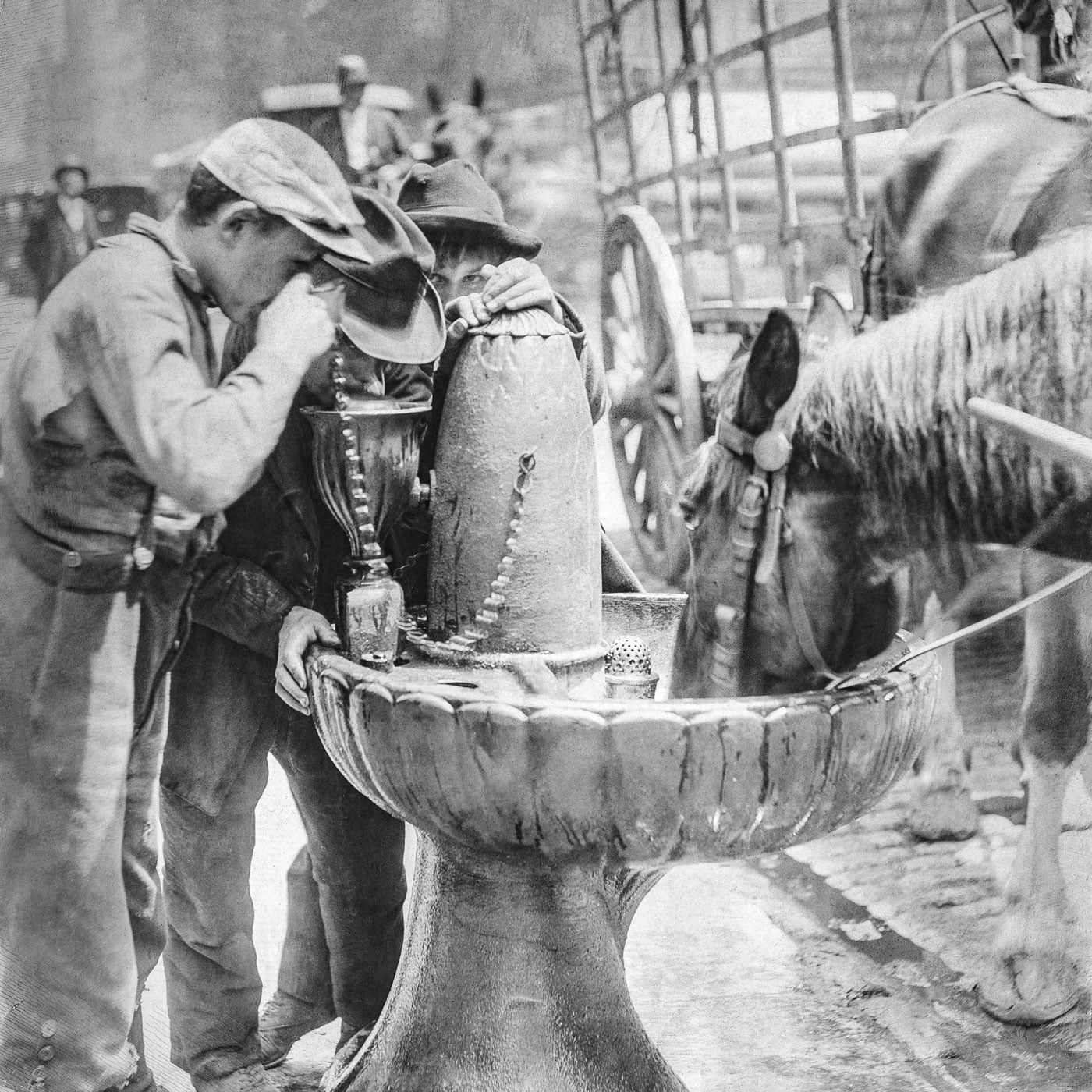

Chicago had a couple of things working against it when it came to healthy water: its low-lying geography, and a lack of reliable, sanitary infrastructure. The city was flat, creating an inherent drainage problem. It had wooden sidewalks, dirt roads, and no sewers. People often dumped their waste into the street or into the backyard. In Donald Miller’s book, City of the Century, he writes that the co-owner of the Chicago Tribune, William Bross, complained of the “slime” that would ooze through the cracks in the wooden sidewalks and of the minnows that allegedly emerged from people’s faucets. If the minnows got into the hot water supply, so the legend goes, they would “come out cooked, and one’s bathtub was apt to be filled with what squeamish citizens called ‘chowder.’”

But something worse than fish was coming out of the faucets. With a lack of sewage and waste disposal system, disease was common, and for many years in the mid-19th century, epidemics were rampant, according to the Chicago History Museum’s Encyclopedia of Chicago.

Cholera was one such disease and was spread easily through unclean water. The bacterial disease caused severe diarrhea, vomiting, and dehydration. Some people turned blue from depleted blood oxygen. Approximately 700 people died of cholera during the summer of 1849, according to one Chicago Board of Health report.

“What was really scary about it is you could have a healthy Chicagoan 150 years ago, and that person could get cholera and literally be dead within 24 hours because it was so quick,” Dr. Allison Arwady, the city’s former public health commissioner, told Chicago Stories.

The city turned to a self-taught engineer named Ellis Sylvester Chesbrough to come up with a plan to solve Chicago’s water woes. Chesbrough wanted to create a combined sewer system that would carry both stormwater and wastewater away from the city. Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, Chesbrough had his team build sewers on top of the existing streets, essentially raising the city. The sewers were then covered with dirt, creating a new street. The buildings had to follow, too.

“It seems amazing today that they could do it, but they literally had to use this series of jacks to jack everything up. There [are] still some areas in the city where you can see this, where…the streets have been raised in front of the houses to accommodate the sewers,” Michael Williams, co-author of The Lost Panoramas: When Chicago Changed Its River — and the Land Beyond, told Chicago Stories. “One by one, the city was raised, including the largest buildings. It must have been an amazing time to watch this happen.”

Though Chicago was the first city in America to have a planned sewer system, the sewage still ended up in the Chicago River, which then emptied into Lake Michigan – the source of the city’s drinking water. So Chesbrough had another idea. Rather than getting the city’s drinking water near the shoreline, Chesbrough wanted the city to pull its water from farther out in the lake. It took three years for workers to build a two-mile tunnel out into the lake to a “water crib.” Upon its completion in 1866, the project was a success and brought the city cleaner water.

The spread of diseases slowed with cleaner water. But the city continued to grow, especially amid the rebuilding efforts following the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. More people meant more sewage.

It also meant more industry, including the Union Stockyards, whose animal carcasses, industrial waste, and other foul byproducts ended up in a small fork of the South Branch of the Chicago River called “Bubbly Creek.” On the North Side, there were tanneries and other factories that added even more toxic gunk to the river.

“The problem was more and more people were moving to Chicago, so there was more and more sewage being created.”— Michael Williams, author

“It would’ve been a toxic, soupy, sludgy mess that definitely stunk,” Williams said.

The city got a wake-up call in 1885, after a bad storm carried human and animal waste to the two-mile intake crib way too close for comfort. The crisis was averted after a shift in winds, but it was a reminder that Chicago’s sanitation infrastructure was far from perfect.

“It was one of those kinds of events in the city’s history where it was clear they had to act. They couldn’t say, ‘We don’t have the money. We don’t have the resources.’ It was essential for the survival of the city,” Williams said.

Some Chicagoans had a crazy idea.

Moving Earth

What if the Chicago River could carry polluted water not to Lake Michigan but, say, the Illinois and Mississippi rivers? Chicago’s geography may have caused some of its original sanitation problems, but it would also be part of the solution.

Chicago sits near a subcontinental divide, a point where water flows in two different directions. That means that prior to the reversal of the Chicago River, all the water east of the divide flowed into Lake Michigan, and all the water west of the divide eventually ended up in the Mississippi River via the Des Plaines and Illinois rivers.

More than 200 years before the river was reversed, French explorers Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette came upon a portage – a point at which one could carry a boat across land from one river to another – that the region’s Native American peoples had used for centuries in order to connect with the Mississippi River. Known as the Chicago Portage, Jolliet thought it would be a good place for a canal, connecting the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River for trade and travel. Jolliet’s vision came true in 1848, long after his death, with the completion of the Illinois and Michigan (I&M) Canal.

The I&M Canal was a key part of Chesbrough’s vision, too. His idea was to reverse the flow of the Chicago River by connecting it with the canal to drain sewage away from the city. But that particular canal wasn’t deep enough to carry that load.

After that close call with the water crib following the storm in 1885, a group of citizens demanded something be done about the city’s sanitation. In 1889, a new government agency called the Sanitary District of Chicago, now called the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago (MWRD), was formed. With a population of more than 1 million people by 1890, Chicago had become a big city, and it needed a big solution to its sanitation problems.

The Sanitation District put its plan into motion on September 3, 1892. On “Shovel Day,” officials and dignitaries broke ground on the Chicago Ship and Sanitary Canal. The plan was to build a 28-mile canal that was wider and deeper than the I&M. It would connect the South Branch of the Chicago River in Bridgeport with the Des Plaines River near Joliet, which was on the other side of that subcontinental divide and 40 feet below Lake Michigan.

“If you could dig deep enough,” Williams said, “gravity would then pull it all away from Chicago and it would…save our city.”

Officials flipped a switch that set off dynamite to blow through two piles of rock, and thus a massive – and dangerous – feat of engineering was underway that involved digging through a mixture of soil, clay, and rock.

“They didn’t have the sophisticated technology that we have today. They had horses, carts, and a lot of muscle and dynamite…It was a spectacle. It was impressive.”— Mariyana Spyropoulous, MWRD commissioner

Some stretches of the canal were solid rock for miles, requiring workers to drill holes into which they inserted sticks of dynamite. Steam shovels moved massive amounts of earth.

“Many tourists would come to watch this because it was such a sight to see,” Williams said. “You can just imagine these tremendous explosions happening and these newfangled machines that were really being developed and invented just particularly for this project.”

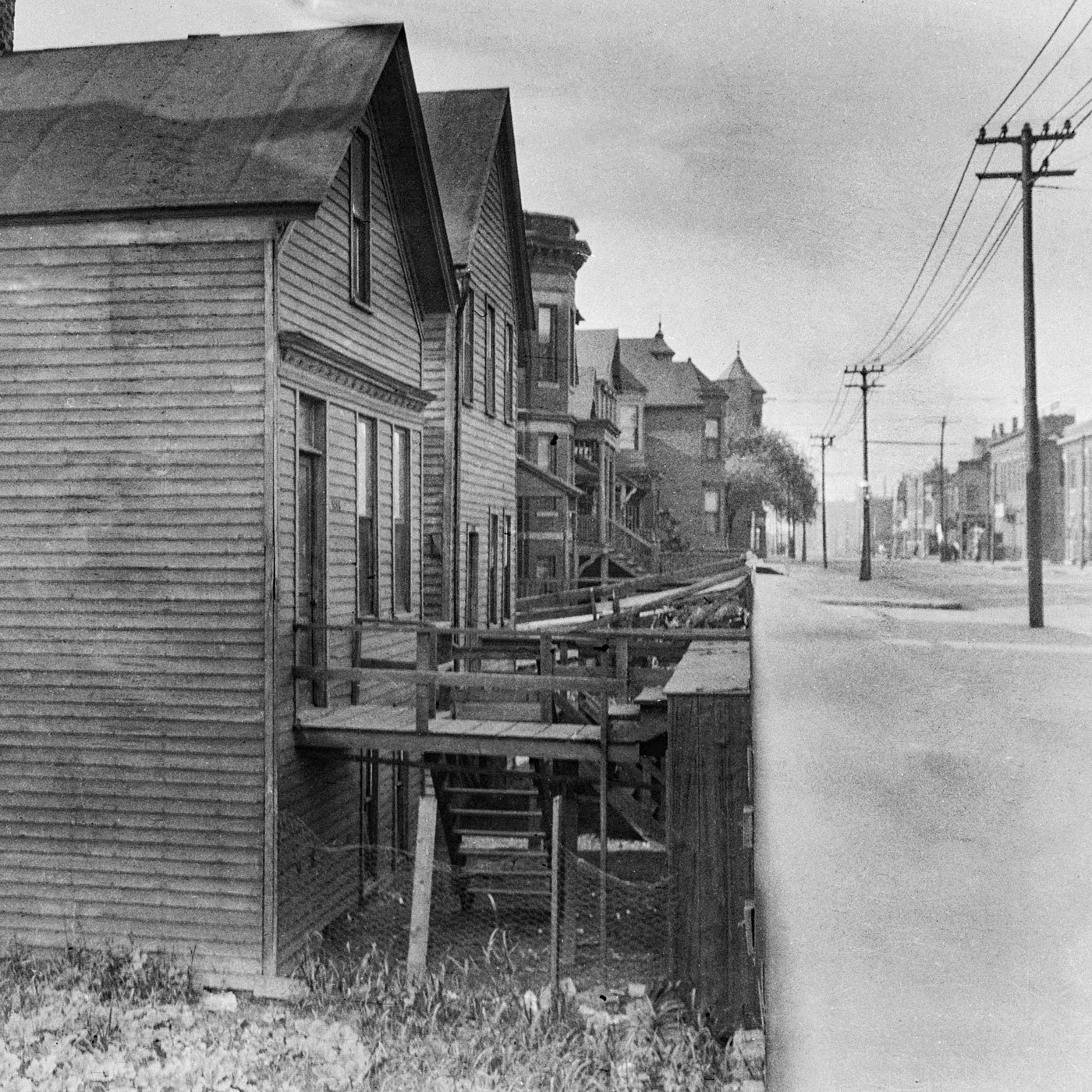

The working conditions for the laborers, who were primarily European immigrants, were difficult and dangerous, and the workers lived in dirty encampments alongside the construction.

“They look like prison camps. They’re just shanties,” Williams said. “The states sent inspectors because there are so many complaints to look at these places. They said that farm animals are living better than these poor people working on the canal.”

Though it was years before the Great Migration, some African American men worked the canal, too. Dr. Lionel Kimble, professor of history at Chicago State University, told Chicago Stories that African American canal workers were typically assigned such tasks as moving dirt, hauling bricks, or digging ditches.

“It was hard work. The African American experience here in the United States has always been one of hard work,” Kimble said.

In the end, the canal workers excavated 42 million cubic yards of rock and soil. After eight years and a hefty price tag of $33.5 million (more than $1 billion in today’s currency), Chicagoans got a taste of the clean water they so desperately needed.

But if dirty water was leaving Chicago, it was inevitably going somewhere else. Since the canal would ultimately send water to the Mississippi River, St. Louis residents had a serious bone to pick with Chicago’s sanitation plan. In 1899, officials in St. Louis sued the Sanitary Districts to try to bring their plan to a halt. But it was too little, too late, Williams said.

“They just dug faster. They moved faster,” Williams said. “They tried to expedite everything as quickly as they could.”

A Reversed River and the Consequences

Early on January 2, 1900, under the cover of the partial darkness of dawn, a few officials went to a makeshift, earthen dam at Kedzie Avenue that was preventing the Chicago River from flowing into the new canal. They wanted to break the dam and fill the canal before a court could halt their work. They attempted to break through, but the ground was frozen solid. Even dynamite was no match for the frozen ground. Eventually, a worker broke through with a dredge, and the river flowed into the canal.

Chicago had done the impossible: it had reversed its river. The water became clearer and cleaner.

“It must have been pretty amazing. No one would’ve ever imagined that what had been this stinky, sewery, dangerous river would’ve looked like that,” Arwady said. “We’ve used science. We’ve used engineering. And then to see that drop off in deaths pay off––we really did something for this city and its ability to grow. So I would’ve made that same decision [to reverse the river].”

Though there were still outbreaks of diseases such as typhoid, they occurred on a much smaller scale. Kimble said the city became a more “hospitable place,” attracting more industry and people.

“African Americans are attracted to Chicago’s growth as an industrial hub,” Kimble said.

“If [the city hadn’t reversed] the Chicago River, would we have had Phillip Armor and Gustavus Swift coming here to open up the packing houses? Would we have had Julius Rosenwald and Sears Roebuck coming to Chicago?”— Dr. Lionel Kimble, history professor

But with the public health and economic benefits of such a drastic change in the environment came unintended consequences, too. Williams said “playing God” in this way did save Chicago, but it also had a profound effect on the ecosystem downstream. The sewage entering the waterways created a kind of “dead zone.”

“The oxygen is being removed from the water, so the fish are dying … or they’re swimming to other areas where they can survive,” Williams said. “The frogs, the turtles, everything that is living in there is being affected by this.”

The reversal also increased flooding and nearly doubled the size of the Illinois River. Farmers whose lands were impacted filed hundreds of lawsuits against the Sanitary District.

One of the bigger cases came from St. Louis, which sued Illinois and the Sanitary District, and the case made it all the way to the Supreme Court in 1906. The Chicago side argued that the sewage was diluted by the time it reached St. Louis. Although St. Louis had a team of experts collecting water samples, in the end, the court decided in favor of Chicago, as the experts couldn’t prove the bacteria found in the water was actually from Chicago.

In 1930, Chicago once again found itself in a legal battle. Other states around the Great Lakes said Chicago was taking too much water out of Lake Michigan. The Supreme Court sided with the other states this time and required the city to either build a dam or a lock to control how much of Lake Michigan flows into the river. The MWRD opted for a lock, which is still in operation. In addition to limiting the flow of Lake Michigan, the lock also helps control potential flooding in the city. For example, in 2020, the MWRD re-reversed the flow of the river and pushed rainwater into the lake after a heavy storm system flooded Chicago’s streets.

Though water filtration and treatment technology eventually helped the ecosystems of the Des Plaines and Illinois rivers rebound, the Chicago River reversal has environmental impacts still felt today. Connecting Chicago’s waterways with the Mississippi River inadvertently created a fish freeway for an invasive species commonly known as Asian carp. The carp were first brought to the U.S. in the 1970s to control algae blooms in treatment and aquaculture ponds in the South, but they quickly got into American waterways and have been a pest to other species of fish ever since.

If Asian carp got into the Great Lakes, it could disrupt the $7 billion-per-year fishing industry. That is cause for concern, as the fish was caught in Lake Calumet, just 7 miles from Lake Michigan, in 2022. Some electric barriers have been installed in the Chicago Sanitary and Ship canal to provide a quite literal shock to any Asian carp trying to swim through it. Officials from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources have even tried “re-branding” the fish as “copi” in the hopes that they could end up on the menu at restaurants.

Though the river reversal created environmental problems the city and state are still dealing with more than 100 years later, reversing the Chicago River altered the course of a frontier town.

“This is what saved Chicago. It’s what allowed Chicago to grow into this enormous city that we know and love. It wouldn’t have been possible had we not done this,” Williams said. “As we go forward trying to make these decisions about what we’re going to do in the future, it’s really important to look back and understand just what we did.”