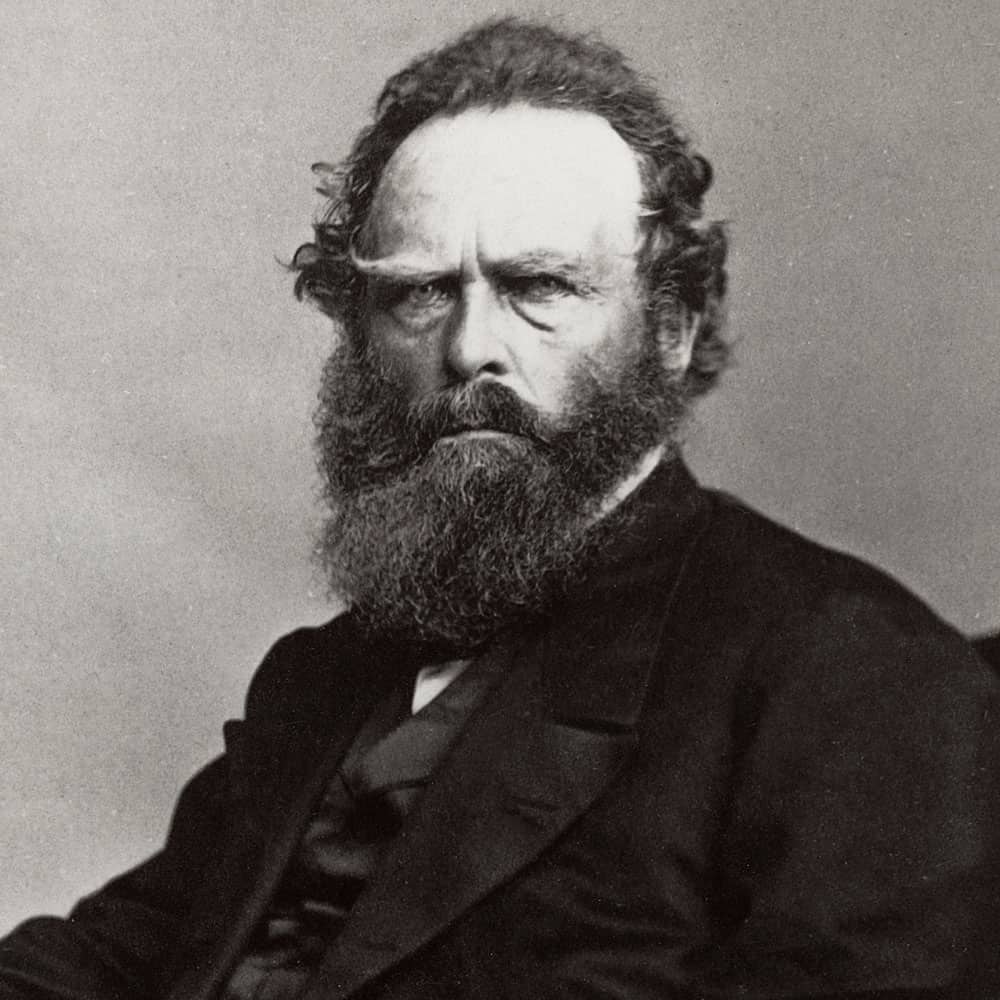

While the ground was still hot after the Chicago Fire of 1871, co-owner of the Chicago Tribune William Bross tried to put a positive spin on the disaster.

“Go to Chicago now!” Bross said in newspaper interviews after the blaze. “Young men, hurry there! Old men, send your sons! Women, send your husbands! You will never again have such a chance to make money!”

On October 11, 1871, three days after the fire started that devastated the city, Bross’s Tribune proclaimed, “CHEER UP. In the midst of a calamity without parallel in the world’s history, looking upon the ashes of thirty years’ accumulations, the people of this once beautiful city have resolved that CHICAGO SHALL RISE AGAIN.”

Bross, who was an avid promoter of the city, predicted that Chicago would be rebuilt in five years and would reach a population of 1 million by the turn of the century, as Donald Miller reports in City of the Century.

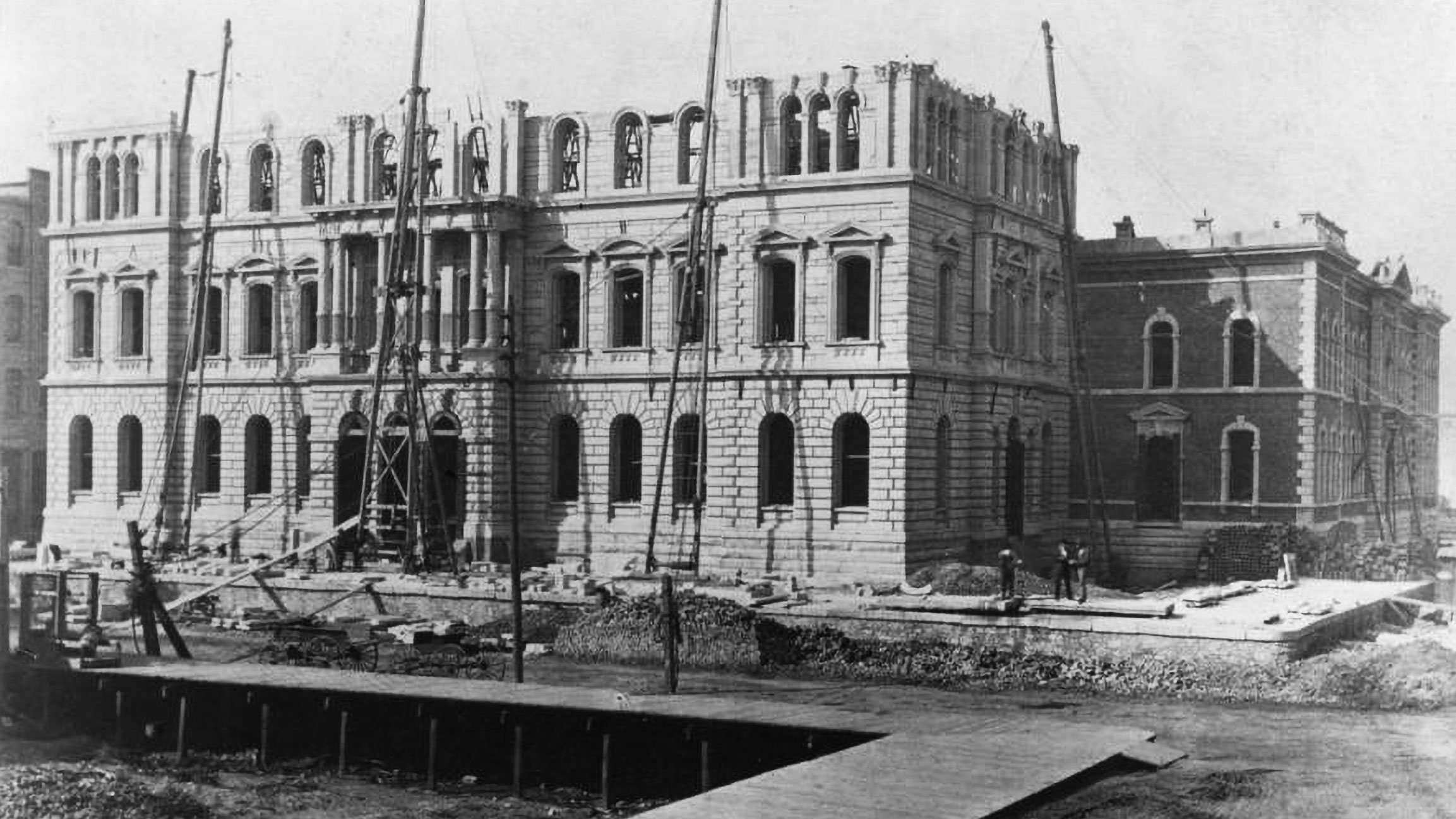

There is an accepted narrative that the fire created a blank slate upon which Chicago was quickly rebuilt. That blank slate allowed it to become a dynamic city of innovative architecture with a fresh skyline dotted with a brand-new building called the skyscraper.

“The great legend of Chicago is that it's a ‘phoenix city’ – it almost instantly rebuilt itself bigger and better from the ashes. And to a certain and significant extent, that's true,” said Carl Smith, professor emeritus of English at Northwestern University and author of Chicago's Great Fire: The Destruction and Resurrection of an Iconic American City.

But the truth behind that legend is a little more complicated.

The Initial Rebuilding Efforts

Chicago did begin to rebuild quickly, since the city’s financial well-being depended on it. Bross described the destruction:

Amid the recovery efforts, Chicagoans set up plenty of makeshift shops and quickly built new structures.

“There was no time to think,” said Jerry Larson, professor emeritus of architecture at the University of Cincinnati. “You had an owner, Marshall Field, wanting to get business going ASAP because he's losing money every day he's not doing business, so you don't have time to think. You've got to put up something.”

Chicago did not immediately become a perfectly fireproofed city right after the fire. In fact, people continued to build with wood.

“Most of the buildings were rebuilt almost exactly as they looked before the fire,” Larson said. Before the fire, Chicago had densely packed wooden buildings, usually no taller than four to five stories, with some stone or brick structures. The city didn’t quite learn its lesson about fire codes and fireproofing, at least not right away.

“There were attempts to improve the building codes, but these were resisted by property owners, both large and small,” said Carl Smith. “While improvements in [the] fire code took place, it was very slow.”

Larson said that Mayor Roswell B. Mason’s successor claimed there would be no more wood in the city.

“Well, that’s a bunch of bull, because all of the lower-middle-class Germans on the North Side wanted the American dream,” Larson said. “They wanted their house. If you eliminate wood construction, they can’t afford it, so all their aldermen stopped all that cold in its tracks.”

Most of the city was rebuilt as it was before within nearly two years, though some of the ruins – particularly burned remnants of train stations – lingered for several years.

“The city did start to rebuild very quickly with the help of insurance money and East Coast money,” said Larson. “But then when the depression hit in 1873, that all dried up and nothing really happened.”

In other words, the city wasn’t fully rebuilt until the early 1880s, when the economy rebounded from the Panic of 1873.

“That's when the rest of the ruined buildings and sites were finally taken over and new buildings erected,” said Larson.

Chicago’s Continued Growth and Safety Improvements

Several years after the fire, the city started to see stricter fire codes, new architecture, and a different urban landscape – but, again, at a slow and steady pace.

Architects and builders began to try out new fireproofing methods. According to Larson, both the Chicago Fire of 1871 and the Boston Fire of 1872 proved that using unprotected iron frames in buildings was pretty much useless against a fire. Then, a second fire in Chicago in 1874 destroyed hundreds of buildings south of downtown, finally waking up the city to the importance of fireproofing. The same year, architect Peter Wight ran a fireproofing test on an iron column. The test took place in a terra cotta oven.

“Guess what? The terra cotta wasn’t hot from the fire,” said Larson. “Somebody had a shazam moment and said, ‘Why are we using wood? We should be using terra cotta.’ And the rest is history.”

Building with materials such as terra cotta-protected iron, brick, marble, and stone, rather than a simple wooden frame, came at a higher cost. Eventually, “New rules are passed that you can't have wooden houses downtown. As a result of that, people who can't afford to build brick houses in the downtown move out,” said Ellen Shubart, a docent at the Chicago Architecture Center.

That meant mostly working-class and poor immigrants were ultimately pushed farther from the city center. But as Carl Smith points out, much like the rebuilding of a safer, more fireproof Chicago itself, that didn’t happen overnight.

“Yes, there were improvements [to the fire codes]. Yes, to some degree these discriminated against poorer people. And yes, they eventually made the city safer. But this was very long and slow, and there was not much enforcement,” said Smith. “It’s not like Chicago was a static thing, and then the fire happened, and people changed their behavior. It’s generally thought that the fire accelerated certain changes rather than caused them.”

Reaching New Heights

“There's a story that immediately after the fire, bingo – we had a bunch of skyscrapers. But that's really not true. It took a good 10 years,” said Shubart.

Both New York City and Chicago – ever in competition – claim the first skyscraper. Larson said that more and more evidence points to New York being able to rightfully take that prize. Though the question of who built the first skyscraper is still up for debate, in Larson’s opinion, the Equitable Life Assurance Building in New York, completed in 1870, was the first because it had the first passenger elevator. But Chicago was preparing to catch up to New York with its own skyscraper, the Kendall Building – until the fire hit.

“The October 1871 issue [of a real estate magazine] had a rendering on its cover of the first skyscraper for Chicago, and seven days later the fire hit and everything stopped cold,” Larson said. Ultimately, the Kendall Building was built after the fire, but it was much shorter than planned, since the fire department wasn’t yet equipped to fight fires in tall buildings.

But Chicago eventually evened the score with New York – and then some. Shubart said that by 1880, architects had developed the Chicago Commercial style (also called the Chicago School) – a style of building still seen in downtown Chicago. Shubart points to the Marquette Building, the Monadnock Building, and the Rookery in Chicago as prime examples. It’s widely recognized that Chicago’s first skyscraper was the since-demolished Home Insurance Building, which was completed in 1885, 14 years after the fire.

While the narrative that Chicago rose from the ashes like a phoenix and built the skyscraper from those ashes took a while to unfold, it’s still partly true. The city celebrated its comeback with the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, showing off not only the site of the fair, but also the city’s new and sophisticated downtown. Bross’s prediction that Chicago would have a population of 1 million people was realized – and 10 years earlier than he predicted.