"The World Will Never Be the Same After This": 50 Years of the Special Olympics

Daniel Hautzinger

June 26, 2018

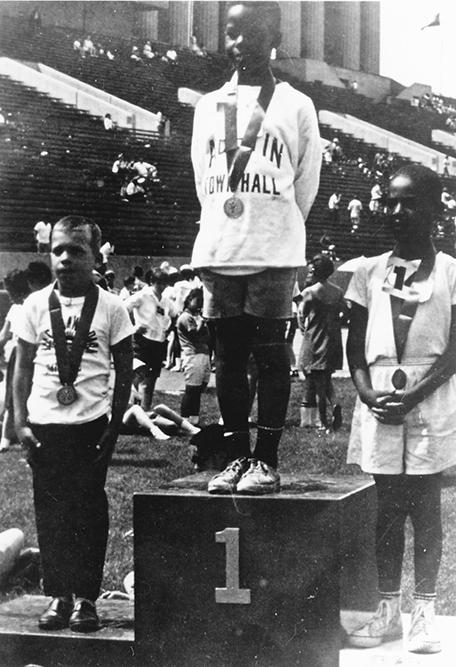

“The most impressive sport spectacle ever to occur in front of this author’s bifocals.” This wasn’t the Cubs’ 2016 World Series victory, or Michael Phelps’ achievement of a record amount of Olympic gold medals, or some thrilling World Cup upset. Rather, it’s how a Chicago Tribune writer described the inaugural Special Olympics, which took place at Chicago’s Soldier Field on July 20, 1968. Almost 1,000 children from twenty-three states and Canada gathered in the arena to take part in some 200 athletic events, from races to high jumps to swimming to baseball. There may not have been many people in the stands, but the presence of celebrated athletes and the awarding of medals (a commemorative one to everyone who participated and bronze, silver, and gold for the top three participants in each event) gave the proceedings a proud official air, and the children seemed to revel in the competition and the spotlight. “This was an affair that touched the heart,” the Tribune correspondent wrote.

While the top three athletes received medals, the games were less about the competition than the affirmation of ability: everyone received a commemorative medal too50 years later, the Special Olympics have grown to become an international organization that offers training and competitions to both children and adults with intellectual disabilities around the world. Special Olympics World Games are hosted every two years, alternating between winter and summer sports, just as in the Olympics, but games, events, and training take place all the time – the USA Games will take place this year from July 1 to 6 in Seattle, Washington. Last fall, the Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame inducted Tommy Shimoda, the first Special Olympics athlete to be so honored, alongside former Cubs pitcher Kerry Woods and Blackhawks captain Jonathan Toews, among others.

While the top three athletes received medals, the games were less about the competition than the affirmation of ability: everyone received a commemorative medal too50 years later, the Special Olympics have grown to become an international organization that offers training and competitions to both children and adults with intellectual disabilities around the world. Special Olympics World Games are hosted every two years, alternating between winter and summer sports, just as in the Olympics, but games, events, and training take place all the time – the USA Games will take place this year from July 1 to 6 in Seattle, Washington. Last fall, the Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame inducted Tommy Shimoda, the first Special Olympics athlete to be so honored, alongside former Cubs pitcher Kerry Woods and Blackhawks captain Jonathan Toews, among others.

To celebrate the Special Olympics’ growth and legacy, various events are planned in the organization’s birthplace, Chicago, on its 50th anniversary. Between July 17 and 21, an international soccer tournament, a festival, a commemorative run of the games’ Flame of Hope, and a concert organized by Chance the Rapper’s production company featuring Smokey Robinson, Usher, Jason Mraz, and other guests, will all take place.

Five decades ago, such festivities and support for people with intellectual disabilities was unimaginable. Intellectual disabilities were stigmatized and little understood, with treatment often meaning consignment to an institution and families hiding their children from the public. During the 1950s and ‘60s, more research began to be directed towards intellectual disabilities, and the cause found a champion in Eunice Kennedy Shriver, the “Kennedy Who Changed the World,” as a recent biography calls her (she was the sister of John F. and Robert Kennedy).

Kennedy Shriver’s own sister, Rosemary, was born with intellectual disabilities made incapacitating by the tragic decision of her father to subject her to experimental surgery: a prefrontal lobotomy that left her unable to walk or speak coherently. Rosemary was often Kennedy Shriver’s athletic partner during the sisters’ youth, and Kennedy Shriver was responsible for reestablishing contact between the family and Rosemary, who had been sent to live in a home and was kept out of the public eye.

Advocating for people with intellectual disabilities became the signal issue of Kennedy Shriver’s life. As the director of her family’s Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. Foundation, she devoted resources to the issue. When her brother was elected president, she pushed him to address developmental disabilities, convincing him to form a Panel on Mental Retardation (as intellectual disabilities were then called) and pass a law to support research and the construction of facilities for people with intellectual disabilities.

Pictured at the announcement proclaiming the Games, from left, Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley; Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. Foundation Executive Vice President Eunice Kennedy Shriver; and Chicago Park District President William McFetridge, alongside two young athletes

Pictured at the announcement proclaiming the Games, from left, Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley; Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. Foundation Executive Vice President Eunice Kennedy Shriver; and Chicago Park District President William McFetridge, alongside two young athletes

In 1962, Kennedy Shriver organized a precursor to the Special Olympics, hosting an athletics-based summer day camp for people with intellectual disabilities in her backyard. Several studies had suggested that physical activity was beneficial for people with intellectual disabilities, and the success of “Camp Shriver” led to the establishment of a few sports programs around the country. The Chicago Park District was charged with implementing a program in Chicago, and a woman named Anne McGlone Burke, who taught children with intellectual disabilities for the Park District, eventually came up with the idea for a city-wide track meet. (You can watch an interview about the Special Olympics with Burke, who is now an Illinois Supreme Court Justice, below.)

Kennedy Shriver pushed Burke to expand the meet into a multi-sport, nationwide event, and the Special Olympics were born. Labor unions supported the games at the behest of Park District president William McFetridge; Governor Samuel Shapiro and Mayor Richard J. Daley gave speeches; and athletes from the Olympian Rafer Johnson to the hockey player Stan Mikita to the astronaut Jim Lovell worked with the children.

In a speech, Kennedy Shriver celebrated the event for proving that children with intellectual disabilities could be just as great of athletes as those without. The Special Olympics and its various arms quickly expanded around the country and globe after the inaugural games. Mayor Daley’s comment to Kennedy Shriver during those 1968 games proved true for people with intellectual disabilities: “Eunice, the world will never be the same after this.”