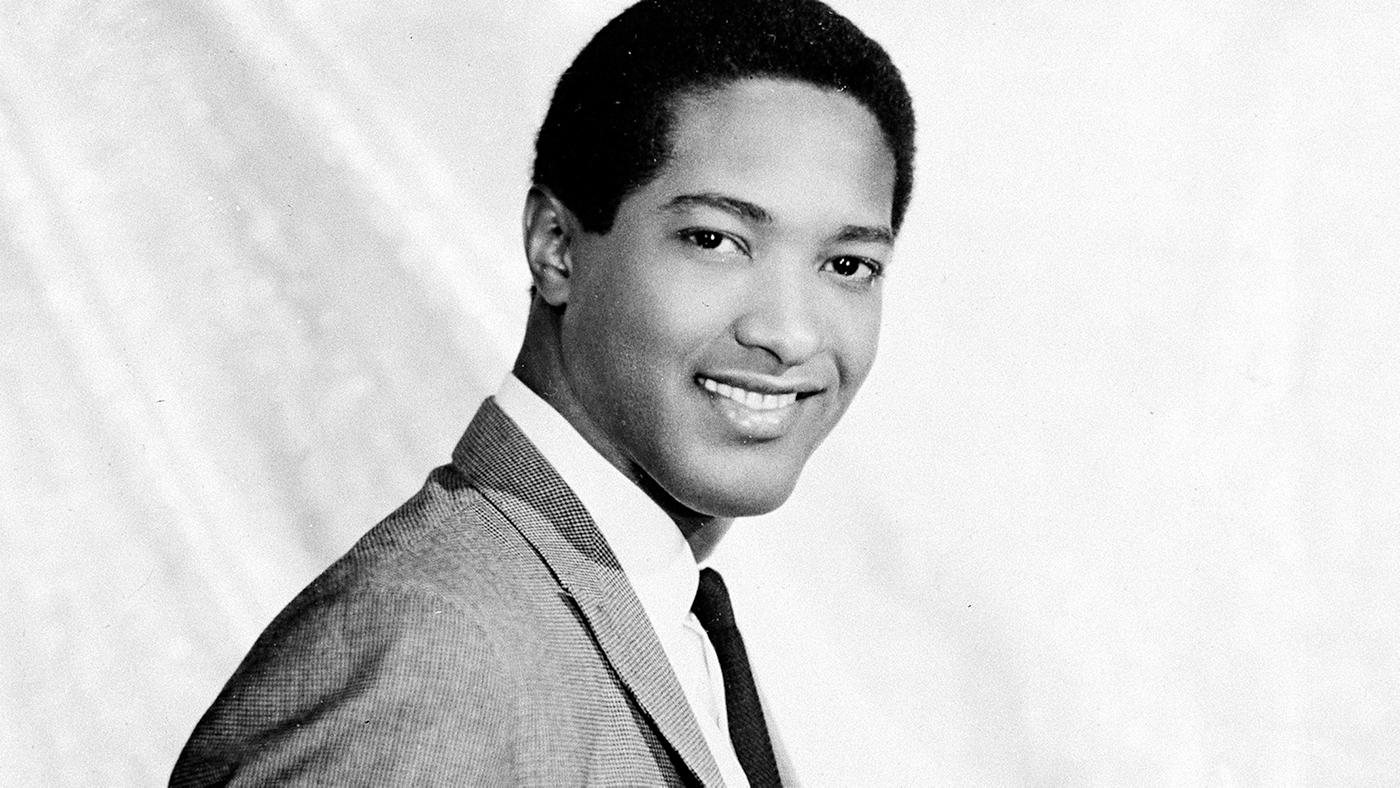

Sam Cooke's Beginnings in Chicago

Daniel Hautzinger

February 21, 2019

Lady You Shot Me: The Life and Death of Sam Cooke airs Thursday, February 21 at 8:00 pm.

Sam Cook was six years old when he began singing in public; 27 years later, after he had added an “e” to his last name and won both black and white audiences across the country as the “King of Soul,” his career ended as prematurely as it had begun, when he was shot and killed in the middle of the night at a $3 motel.

Although he died in Los Angeles, the majority of Cooke’s short life was spent in Chicago. Born in Clarksdale, Mississippi to a minister, his mother and siblings (he was the fifth of eight children) followed his father to Chicago when Sam was two. The family eventually settled in Bronzeville on Cottage Grove Avenue near 35th Street, blocks from the lake and Doolittle Elementary School, where Sam and his siblings would attend classes.

Sundays were taken up entirely by church, with Sunday school and multiple services. The Reverend Cook led a congregation at the Christ Temple Church in Chicago Heights, south of the city, and he always introduced his sermon with a song. Recognizing the musical talent of his children, he organized them into a quintet that he called the Singing Children. Sam, the second youngest, sang tenor; his four-year-old brother L.C. took bass.

As the Singing Children gained experience performing at their father’s church, they began to sing at other churches, too, traveling as far afield as Indianapolis and Kankakee with the Reverend and their mother. Sam was ambitious even at a young age. “Hey man, I ain’t never gonna work,” L.C. remembers his brother saying. “I’m going to sing for a living.” He longed to replace his older brother or sister as lead vocalist. But the Singing Children stopped performing before he could: after World War II ended, one brother enlisted in the air force, while Sam’s oldest sister immersed herself in married life.

By then, Sam was in high school at Wendell Phillips, the same school Nat “King” Cole had attended. He told L.C. that one day he would be as famous as Cole. And, with L.C. in tow, he struck out to perform solo, singing for passengers disembarking at the end of the streetcar line near his house while L.C. passed a hat around to collect money.

One day in 1947, two brothers heard Sam singing (legend has it he was serenading a girl) and asked him to join a fledgling gospel quartet that they soon named The Highway QCs. Within a year, the QCs were performing in concerts with better-known groups such as the Soul Stirrers in Detroit and Memphis. (Sam had been so stunned by the Stirrers when he first heard them live that he refused to perform with the Singing Children after them, as had been planned.) By 1950, when the lead vocalist in the Stirrers quit, Cook was ready to replace him. He was 19, and his career as a star had begun.

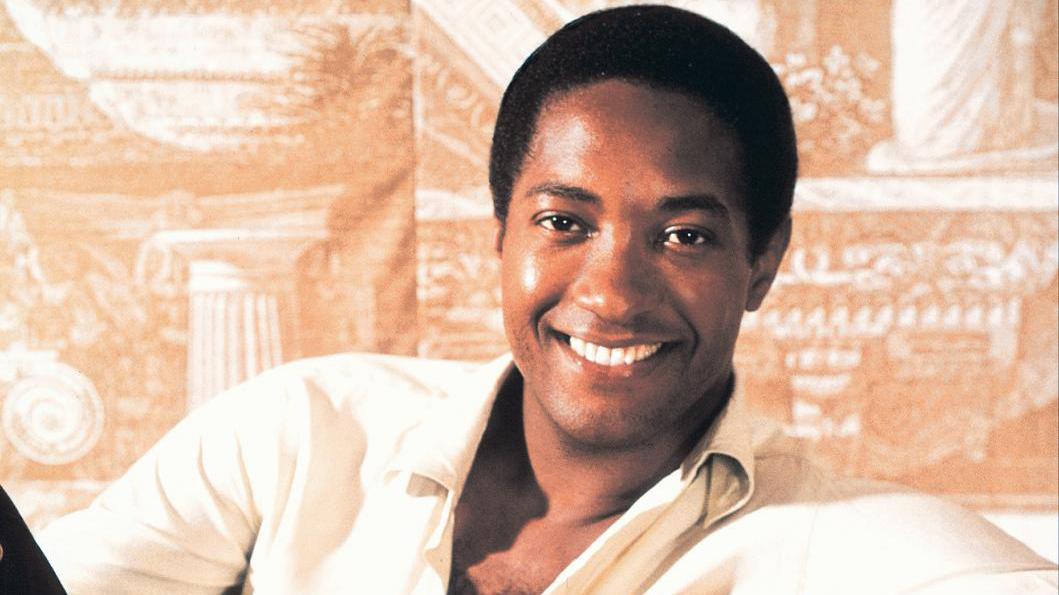

It really took off in 1957, when he moved to Los Angeles and crossed over from gospel to pop with the hit “You Send Me.” He became one of the first black artists to sign with RCA in 1960, and, despite some of the schlocky tunes they handed him, began to rack up even more hits, including songs he himself had written, such as “Wonderful World” and “Chain Gang.” He had 29 Top 40 hits over the course of his abbreviated career; four of them reached the Top 10. He founded a record label in 1961 – African American label owners were a rarity – to produce up-and-coming gospel talent, and eventually also owned a publishing company.

In 1963, he, was arrested in Louisiana with his wife and two friends for trying to get a room at a whites-only motel. That experience, along with Bob Dylan’s protest song “Blowin’ in the Wind,” inspired him to write his most enduring song, “A Change is Gonna Come.”

Before it was released as a record, however, Cooke’s life ended in a sordid manner that is still shrouded in controversy. The manager of the Hacienda Motel in Los Angeles shot a pistol three times, hitting Cooke once in the chest, when he allegedly ran into her office demanding to know the whereabouts of a prostitute with whom he had checked into the motel. His companion had taken his clothes, and Cooke was inebriated. It was the middle of the night. His last words were, reportedly, “Lady, you shot me.”

“A Change is Gonna Come” came out later that month, after Cooke’s two-city funeral attracted enormous crowds. Despite the winter cold, Chicago’s streets overflowed with mourners outside a public viewing of Cooke’s body, while his wife and daughters had to be lifted over the crowd to get inside the church. Cooke’s friend Cassius Clay (later Muhammad Ali), who had called him “the world’s greatest rock ‘n’ roll singer,” attended. In Los Angeles, Cooke’s body was displayed inside a plastic case for three days. Ray Charles sang “The Angels Keep Watching Over Me” at the service there.

Now, although many people don’t realize that Cooke spent most of his formative years in Chicago, he is honored with a stretch of street near his childhood home. Close to where an ambitious, angel-voiced young boy once sang to passersby for money, there is now a Sam Cooke Way.