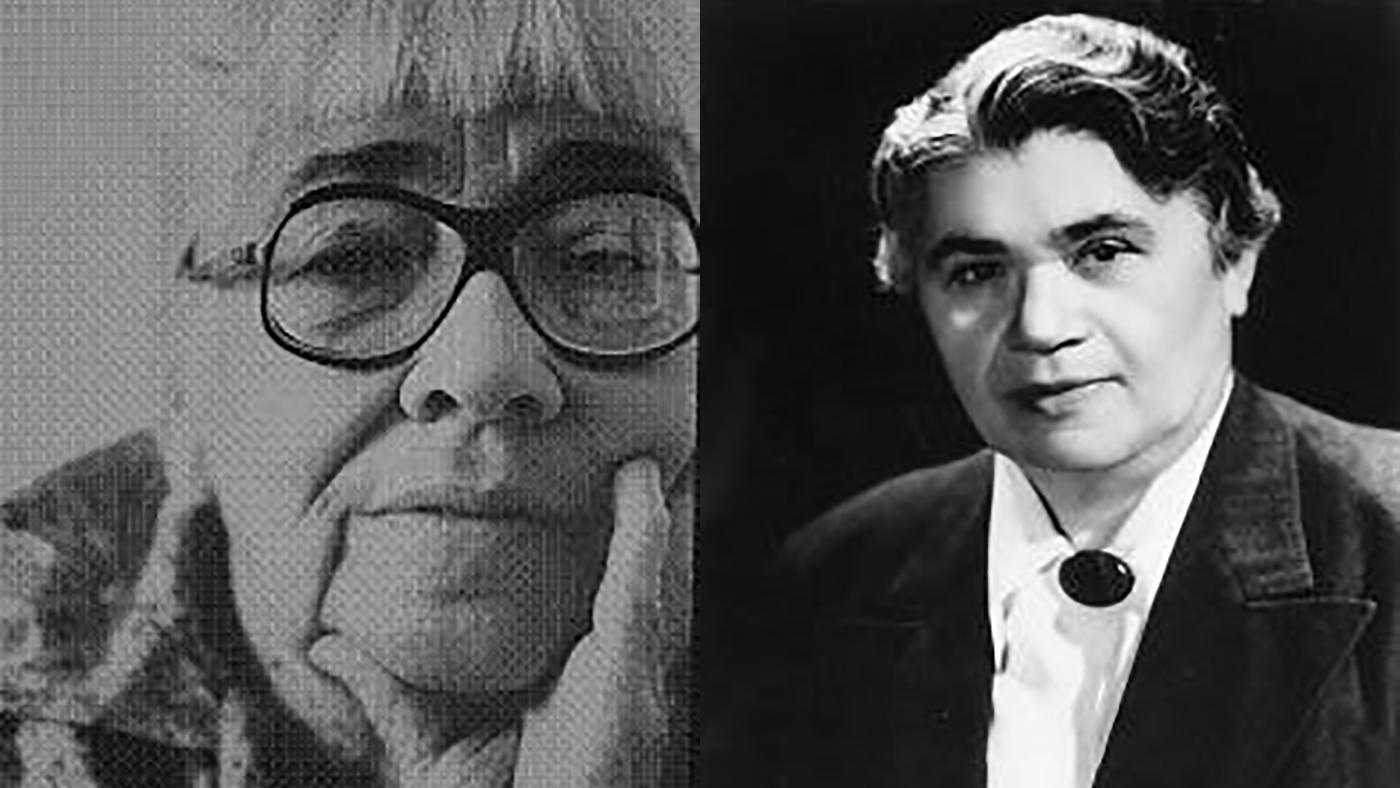

Chicago's Outspoken Lesbian Power Couple

Daniel Hautzinger

June 18, 2019

In 1957, lawyer Pearl M. Hart defended a Chicago newspaper proofreader named George Witkovich before the United States Supreme Court. Witkovich was a victim of the liberty-restricting campaigns of the Red Scare, having been ordered for deportation to his native Yugoslavia for being a Communist and then indicted for refusing to answer questions about his conduct while under government supervision.

Hart won the case for Witkovich. She also helped defend Claude Lightfoot, the leader of the Illinois Communist Party, in a case brought under the Smith Act, which forbade advocating the violent overthrow of the government.

Hart herself could easily have been caught up in and ruined by the 1950s Cold War hysteria over the exagerrated threat of malicious foreign agents. At the time, the federal government was carrying out mass firings and persecution of gay and lesbian government workers in a “Lavender Scare” that cast homosexuals as seditious and open to blackmail.

Hart herself was a lesbian; in fact, she was probably the first lesbian lawyer to appear before the Supreme Court. At the time that she was defending Witkovich, Lightfoot, and other immigrants prosecuted in the fever of anti-Communism, she was living with an actress named Blossom Churan, with whom she had been involved since the 1920s, as well as physician Bertha Isaacs, who moved in during the 1940s.

Years earlier, Hart had begun making her reputation while working with another prominent social rights crusader who could be considered a lesbian, though she didn’t identify as such: Jane Addams, the founder of Hull House, who was involved in a romantic relationship with Mary Rozet Smith for forty years. Hart’s family had moved to Chicago from Michigan when she was four, and after graduating from John Marshall Law School (where she later taught) and passing the Illinois bar in 1914, she began working with Addams on juvenile legal issues. She was considered a foremost authority on the topic and drafted adoption laws and related statutes for Illinois.

She also defended women in Chicago’s Morals Court; she was the only woman in the city practicing criminal law at the time. She unsuccessfully ran for Municipal Court judge twice, in the 1930s and 1940s, and for City Council in 1947 and 1951. (Chicago didn’t elect a female alderman until 1971.)

In the 1950s and ‘60s, Hart began quietly organizing to help other gay and lesbian people. She was involved in two short-lived Chicago chapters of the Mattachine Society, which, though secretive, sought to advance the cause of homosexuals by garnering support from medical and psychological experts and castigating newspapers that printed the names of people arrested in raids on gay bars. In 1965, she became a founding member of a more outspoken and successful group, Mattachine Midwest, acting as its legal adviser.

It was through these organizations that Hart met Valerie Taylor, a writer who had been invited to lecture about lesbian literature at a Mattachine Society meeting in Chicago. Taylor said that Hart became “the love of [her] life,” and Taylor moved into an apartment around the corner from Hart’s home, so as not to disrupt the “neurotic situation” or “rather gothic existence,” as Taylor called it, of Hart, Isaacs, and Churan’s living arrangement.

Taylor herself was becoming an important figure in Chicago’s LGBT community. Born in Aurora, Illinois in 1913, she married in 1939 and worked first as a rural schoolteacher and then an office worker. She supplemented her income by publishing poems and short stories in various magazines under pseudonyms. In 1953, she sold her first novel, a romance called Hired Girl, under the name Valerie Taylor. With the proceeds, she divorced her alcoholic, abusive husband and moved with her sons to Chicago, where she found work as a proofreader and assistant copy-editor.

While demonstrating for tenant’s rights, gay rights, and anti-war groups, Taylor began writing lesbian novels, as well as poems and reviews for the magazine of the first lesbian rights group in the United States, the Daughters of Bilitis. Her first lesbian romance, Whisper Their Love, was published in 1957 and sold two million copies. She followed it up with four more lesbian novels in the 1960s, as well a gothic novel.

Meanwhile, she was becoming a more visible presence in LGBT groups. With Hart, she became involved in Mattachine Midwest, writing and editing its newsletter and often serving as the women’s voice of the organization, as when she appeared on Phil Donahue’s popular talk show to discuss homosexuality alongside the sexologists William Masters and Virginia E. Johnson. She co-founded the national Lesbian Writers’ Conference in 1974.

Hart fell deathly ill the next year. Taylor was refused entry to Hart’s hospital room because she was not family, despite their intimate relationship. Only with the help of one of Hart’s legal protégés did Taylor finally gain access; by then, Hart was in a coma, and died soon after.

Taylor moved to Tucson in 1979, continuing to publish lesbian novels that now had a more feminist bent. Hart was inducted into the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in its inaugural year, 1991; Taylor followed in 1992, and died in 1997.

Hart’s name lives on in the Gerber/Hart Library, an LGBT library begun by historian Greg Sprague in 1978 as the Chicago Gay History Project and renamed Gerber/Hart in 1981. Taylor’s name survives in her novels. But both women’s legacies are most important in the lives of the people they helped, from the immigrants Hart defended to the LGBT people both of them staunchly defended.

Learn more about Valerie Taylor, Pearl Hart, and Chicago's LGBT history in our documentary Out & Proud in Chicago, narrated by Jane Lynch.