Chicago's Starring Role in the Creation of Baseball's Negro Leagues, 100 Years Ago

Daniel Hautzinger

July 15, 2020

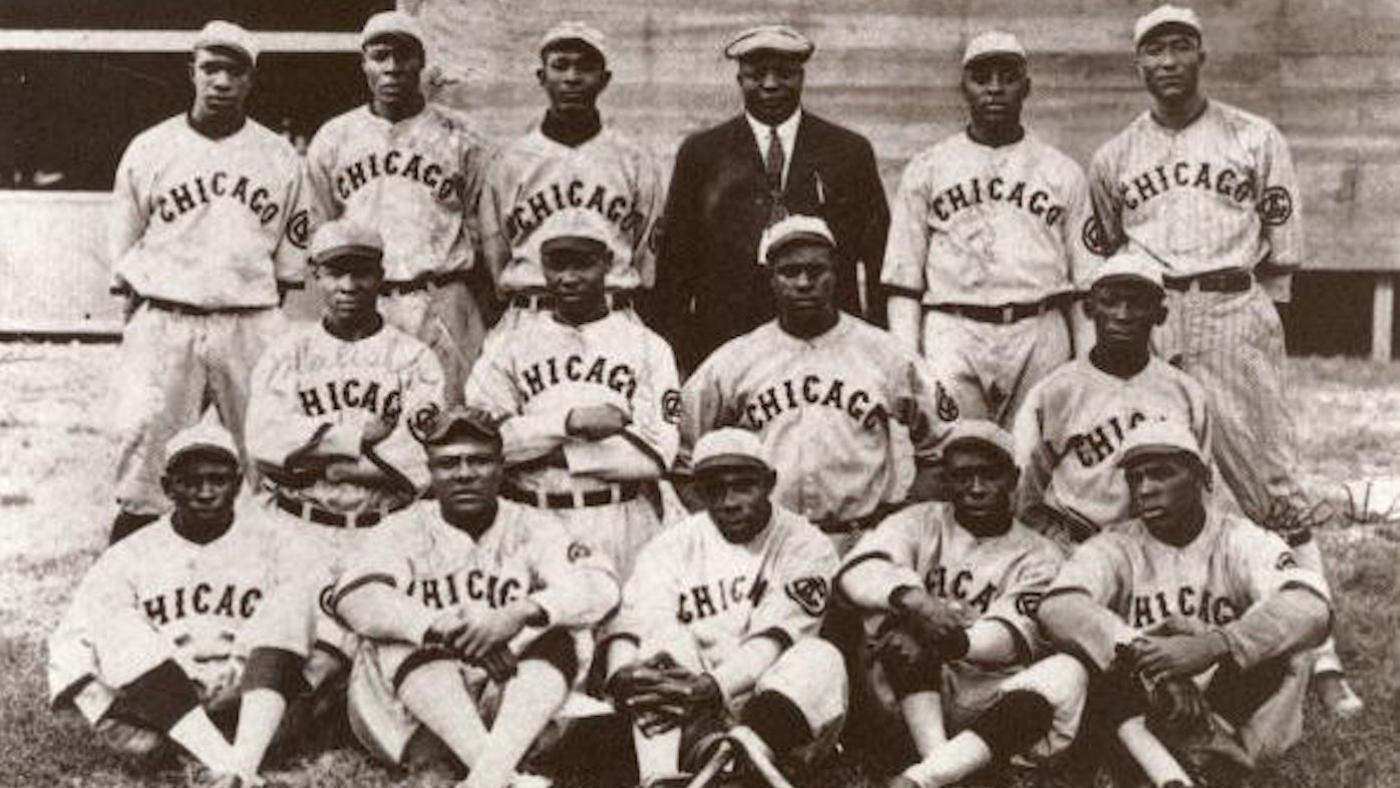

Chicago looms large in the creation of baseball’s Negro Leagues, which existed alongside the segregated major leagues from 1920 until about 1960. When the Negro National League was founded 100 years ago in 1920, Black baseball’s best team was the Chicago American Giants, who were headed up by Andrew “Rube” Foster, a dynamic manager and former pitcher who was the driving force behind the creation of the league.

But the need for a separate professional league for African Americans was due in part to another famed Chicago player-manager who decades earlier helped solidify the sport’s color line.

“I’ve always considered Chicago the mecca of Black baseball,” says Larry Lester, the co-founder of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri and the author of numerous books on Black baseball, including Rube Foster in His Time and Black Baseball in Chicago. “Rube Foster was the kingpin of Black baseball. He’s an innovator, a creator, a brilliant statistician who had a Rolodex mind. He’s probably Black baseball’s greatest visionary.”

Foster was born in Calvert, Texas in 1879, and left school after eighth grade to try to make a career in baseball. A towering figure, he played for several independent teams across the country, acquiring a formidable reputation as a pitcher. Rumors swirl that he fared well in matchups against the likes of Cy Young and gave lessons to pitchers for the New York Giants on the request of their legendary manager John McGraw, while fellow players praised him, with Honus Wagner calling him “one of the greatest pitchers of all-time.”

Despite his skill, Foster was never able to officially prove himself against any of those white players, or even join them on a team—hence the rumors and the covert nature of his relationship with McGraw. Professional major and minor league baseball had refused to allow Black players since the 1890s.

There had been a few Black big league ballplayers in the 1880s, notably Moses Fleetwood Walker, the first major leaguer known to be an African American. (The mixed-race William Edward White played a major league game in 1879 but passed his whole life as white.) Walker joined the semi-pro Toledo Blue Stockings as a catcher in 1883—an acquisition nearly prevented by an objection from a Peoria representative of Toledo’s league who didn’t want Black players in the league.

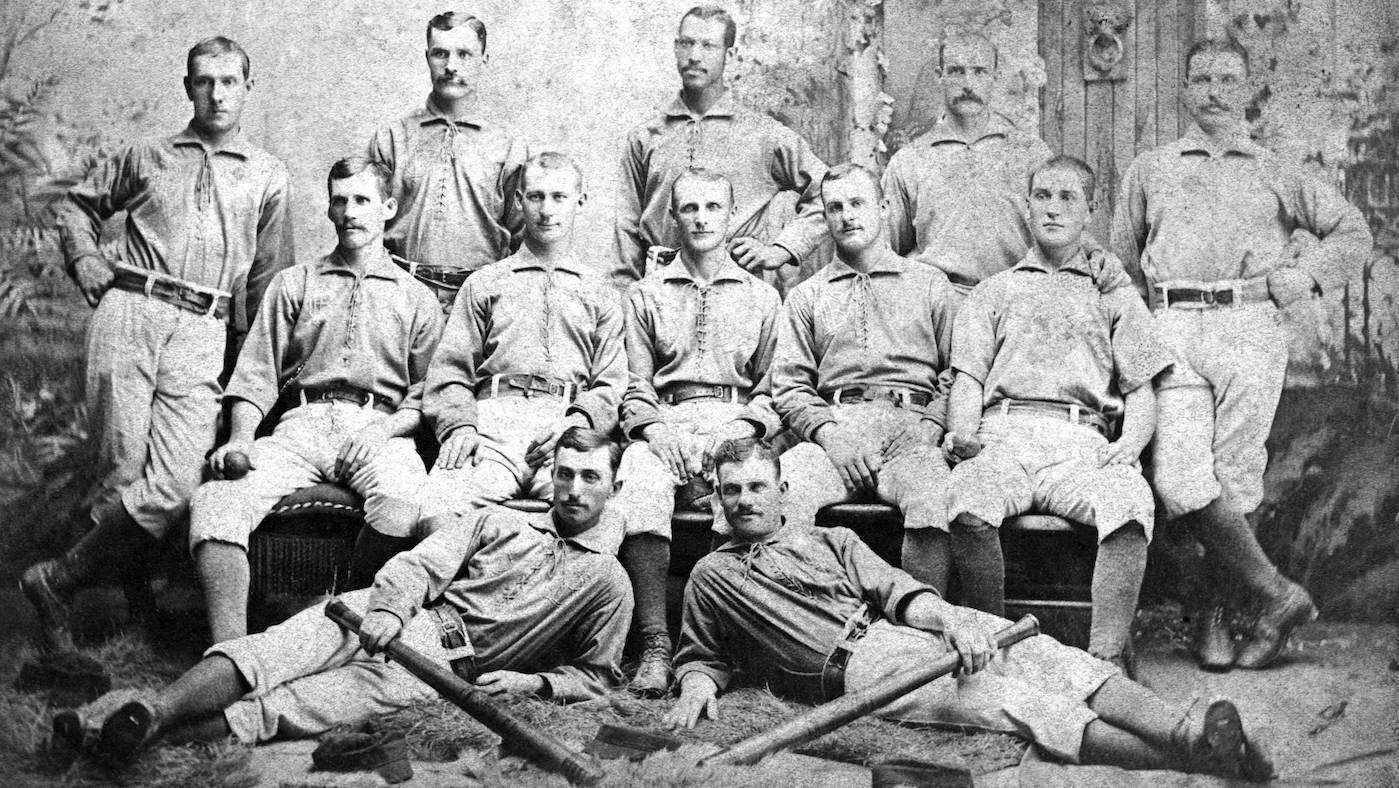

The 1884 Toledo Blue Stockings, with Moses Fleetwood Walker in the center top row. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The 1884 Toledo Blue Stockings, with Moses Fleetwood Walker in the center top row. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In August of 1883, Chicago’s White Stockings (later the Cubs) faced the Blue Stockings in Toledo for an exhibition game. Adrian “Cap” Anson, Chicago’s star player-manager, refused to play against a team fielding a Black player. While the game eventually went on so that the White Stockings wouldn’t lose their profit, the celebrity Anson’s vocal opposition to integration helped enact baseball’s color line. Walker managed to remain with Toledo through 1884, when the team became part of the majors, but he didn’t last the season. He was the last Black player in the major leagues until Jackie Robinson broke the color line six decades later, in 1947.

In the decades since the 1890s, Black ballplayers like Rube Foster had to play on barnstorming independent teams without formal organizations behind them. There were periodic attempts to create an African American professional league, “but they all failed for a variety of reasons,” says Leslie Heaphy, an associate professor of history at Kent State University at Stark whose research focuses on the Negro Leagues and women in baseball.

But the desire for a Negro League remained. “It lends legitimacy and credence,” explains Heaphy. “When you put an organization, professionalism, and contracts behind something and allow people to make a living and call this a job, you’ve changed the nature of what they’re doing.”

So in February of 1920, Foster—by then the owner and manager of the stellar Chicago American Giants, which he had formed in 1910—gathered the owners of seven other Midwestern Black teams at a Kansas City YMCA. “He was dedicated to putting a viable league on the field,” says Larry Lester. “He had articles of incorporation already drafted, he had an attorney, he had some sportswriters at that historic meeting to make sure the message got out to the public. The rosters were already formed—in fact, he sent his star player, Pete Hill, to the Detroit Stars so that the league would be somewhat balanced. He had a plan.”

And thus the Negro National League was born. The Negro Southern League was formed the same year—“considered by many as more like a minor league system even though officially it wasn’t seen that way,” says Heaphy. (1920 was also the year Kenesaw Mountain Landis became the first commissioner of major league baseball. According to many historians including Heaphy, Landis opposed the integration of baseball.) The Eastern Colored League came about in 1923, allowing for the Negro League World Series starting the following year. In 1933, the East-West classic—the equivalent of the major league all-star game—began, with the premier game played at Chicago’s Comiskey Park.

Negro League teams often played at major league ballparks, generating income for the major league owners through leasing, as Heaphy points out. “Some people argue that the Negro Leagues shouldn’t be considered different from the major leagues because they were playing the exact same rules, same equipment, sometimes the same stadiums,” she says. Negro League baseball does seem to have been faster-paced and flashier, she says, citing the commonality of stealing home plate, a tactic Jackie Robinson brought to the majors. Some teams eventually built their own stadiums, such as the Pittsburgh Crawfords’ Greenlee Field. (The American Giants played at the White Sox’s first field, South Side Park.)

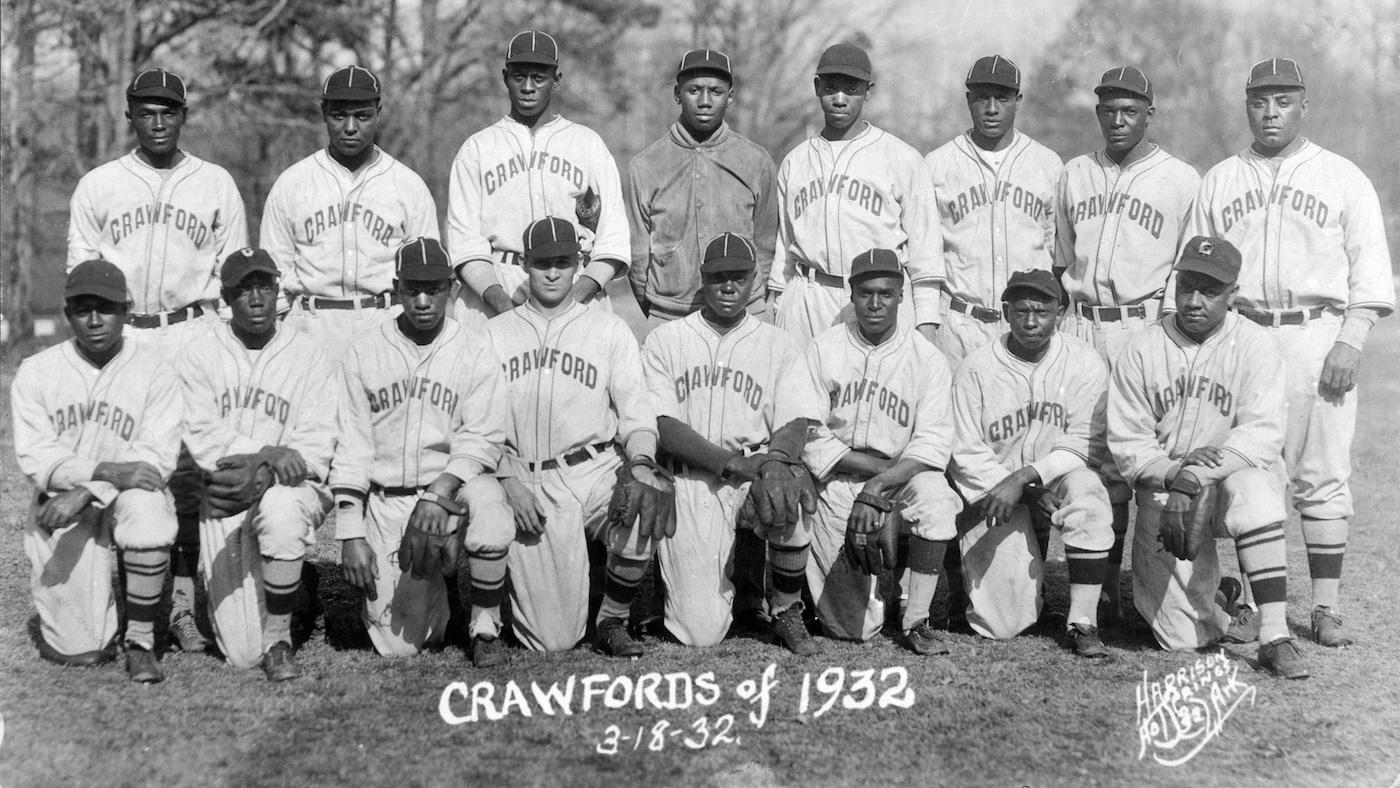

The 1932 Pittsburgh Crawfords, including Satchel Paige (top row, third from left) and Josh Gibson (to the right of Paige). Photo: Harrison Studio/Wikimedia Commons

The 1932 Pittsburgh Crawfords, including Satchel Paige (top row, third from left) and Josh Gibson (to the right of Paige). Photo: Harrison Studio/Wikimedia Commons

And yet the Negro League ballplayers still had to endure the racism of the country, as every African American did, being barred from various hotels, restaurants, transportation, and public accommodations while traveling for games. “They knew which boardinghouses they could stay in, what restaurants would accommodate them,” says Lester. “They would plan out their stops on the road, which gasoline stations they could stop at.”

But he says that the Negro Leagues also helped support other Black businesses—a goal of Foster, who was inspired to form the Negro National League in part by the violence of the Chicago race riots and Red Summer of 1919. “They had Black-owned hotels to stay at, they could eat at Black-owned restaurants, transportation was provided by Black-owned cab companies and bus companies. It had a rippling effect, creating other Black businesses along the way. This empowered African Americans to create jobs and reap the benefits,” says Lester.

“They had to figure out how to navigate around the racist, troubled waters,” he continues. "This is why the League’s motto was, ‘We are the ship; all else the sea.’ ”

Rube Foster didn’t get to see much of the Negro Leagues. He had a nervous breakdown in 1926 and was institutionalized in an asylum in Kankakee, where he remained until his death in 1930. Without his leadership—he sometimes even contributed the payroll for struggling teams out of his own pocket—the Negro National League collapsed.

Various other leagues followed, until the major league’s slow integration over twelve years starting in 1947 drew talent away, leading to the demise of the Negro Leagues by the early 1960s. In 1951, the Cuban ballplayer Minnie Miñoso joined the White Sox, becoming Chicago’s first Black major leaguer—he had started his American career with the Negro National League’s New York Cubans. Two years later, Ernie Banks left the Negro League’s Kansas City Monarchs for the Chicago Cubs to become that team’s first Black player.

In between the two players’ major league debuts, the Chicago American Giants folded, in 1952. They won five of the first seven championships in the Negro National League founded by their powerful owner and manager, Rube Foster, and yet they, along with Foster and the entirety of the Negro Leagues, are barely known today.