When Chicago Hosted Olympics-Style Games — And Why They Have Been Forgotten

Daniel Hautzinger

July 8, 2021

Chicago is so proud of the World’s Fairs it hosted—in 1893 and 1933—and their effect on the city that they are memorialized on the Chicago flag as two out of the flag’s four red stars. We’re less proud of, but still remember, the failed and contentious bid for the 2016 Olympic Games. Forgotten almost completely is the time Chicago did host an international, Olympic-style sports competition: the 1959 Pan-American Games.

The Pan-American Games haven’t left a mark in Chicago’s mythology in part because they didn’t leave much of a physical trace, unlike the World’s Fairs—the only structure built for the Games that remains today is Portage Park’s swimming pool. But there are other reasons as well, as University of Chicago scholar of the Olympics John MacAloon has argued: Chicago took charge of the Games relatively late; their planning was marred by official expressions of doubt about Chicago’s preparedness; and, perhaps most of all, the Games were not all that successful, and were tarnished by a sordid coda. Since the 1959 Pan-American Games weren’t something to be all that proud of, Chicago has chosen to forget them.

Cleveland was supposed host the Games, the third of their kind and the first in the United States. But the Ohio city’s bid relied on a pricy contribution from the federal government, despite Washington’s history of refusing to pay for international sporting events in order to avoid the appearance that the federal government was sponsoring the event. In 1904, Chicago had ceded the third Olympic Games to St. Louis in part because St. Louis was hosting a World’s Fair and could thus use federal money appropriated for that event to help with the Olympics.

As St. Louis had replaced Chicago, so half a century later did Chicago replace Cleveland. In August, 1957, after Cleveland backed out of hosting, Chicago won its bid to take over the 1959 Pan-American Games. Richard J. Daley, then only two years into his tenure as mayor, lobbied for the Games as a way to demonstrate Chicago’s stature, just as his son Richard M. Daley would decades later in the bid for the 2016 Olympics.

More than twenty nations took part in the third Pan-American Games, the first to take place in the United States. Photo: Chicago History Museum

More than twenty nations took part in the third Pan-American Games, the first to take place in the United States. Photo: Chicago History Museum

Pan-American officials quickly began to doubt that Chicago understood the magnitude of what it had taken on, or that it would be able to pull it off successfully. Col. Jack Reilly, Chicago’s Director of Special Events and Daley’s appointed head organizer of the Games, came in for special condemnation for his seemingly lackadaisical approach. Officials stated their concerns publicly in order to goad the city into action.

It worked, to an extent: the committees in charge of planning the Games were reorganized. Carl Stockholm, a dry-cleaning magnate and former Olympic cyclist, became chairman, heading up a committee that included two other former Olympians: swimmer Michael McDermott and sprinter and alderman (later congressman) Ralph Metcalfe.

And yet the change didn’t help. Stockholm soon resigned as chairman, citing conflict with Reilly. “You and your executive director [Reilly], to my best knowledge and belief, do not realize the importance of properly financing and arranging the multitudinous details necessary for events such as the Pan-American Games,” he told Daley. Six months before the Games were set to open, he found Chicago’s budget unrealistic, just as Cleveland’s had been.

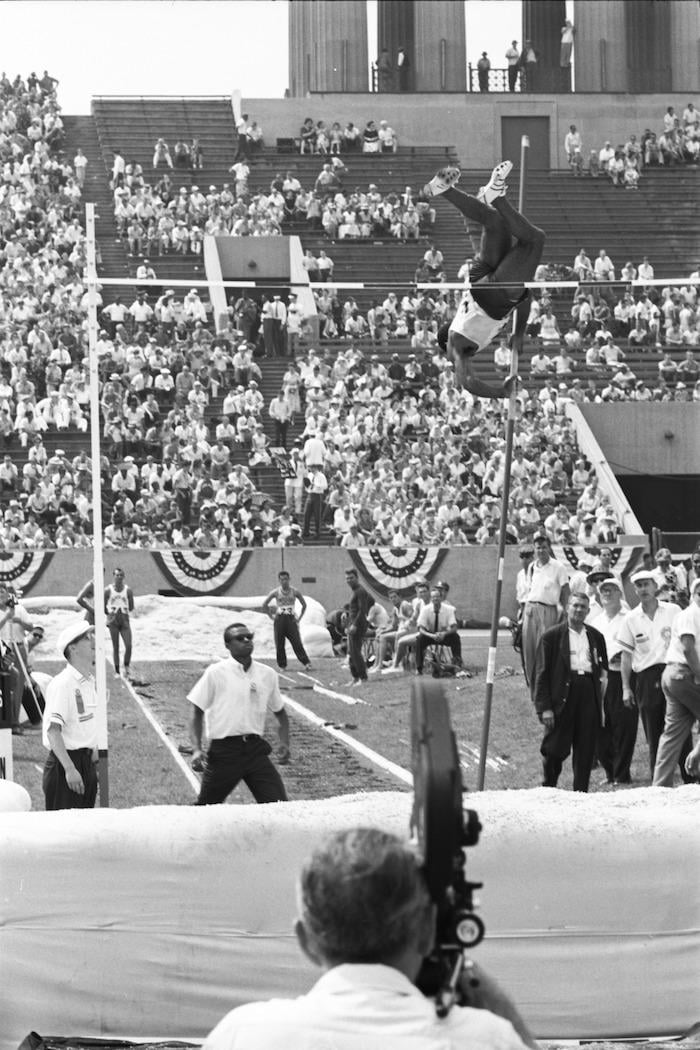

Competitions occurred in twenty sports at venues all across Chicagoland. Photo: Chicago History MuseumBut where Cleveland had failed in extracting federal money, Chicago succeeded—the only time the federal government has directly contributed to an international sports competition. (Modern federal grants have been for transportation and security.) The recent success of the Cuban Revolution may have helped secure the grant—as the Cold War neared the shores of the United States, the government wanted to inspire good will amongst other Latin American countries as a bulwark against Communism. The grant for $500,000 was a tenth of what Cleveland had requested, and was meant to pay only for the transportation, housing, and feeding of athletes from other countries. It, along with a desperate grant from Chicago’s City Council, helped keep the Games afloat.

Competitions occurred in twenty sports at venues all across Chicagoland. Photo: Chicago History MuseumBut where Cleveland had failed in extracting federal money, Chicago succeeded—the only time the federal government has directly contributed to an international sports competition. (Modern federal grants have been for transportation and security.) The recent success of the Cuban Revolution may have helped secure the grant—as the Cold War neared the shores of the United States, the government wanted to inspire good will amongst other Latin American countries as a bulwark against Communism. The grant for $500,000 was a tenth of what Cleveland had requested, and was meant to pay only for the transportation, housing, and feeding of athletes from other countries. It, along with a desperate grant from Chicago’s City Council, helped keep the Games afloat.

Ticket revenues never seemed to have been reported, and were probably low, according to MacAloon. (The lack of records about the Pan-American Games is another example of their erasure from Chicago’s civic memory.) After the Games opened on August 27, 1959, attendance was also sparse. Crowds never exceeded 11,000 people in a day at Soldier Field.

Competition occurred in 20 sports, at venues ranging from Waukegan and Libertyville to the Cal-Sag Channel and Oak Brook. For the most part, events were held in existing facilities—gymnastics was held at Navy Pier—given the short timeline and limited budget to construct new ones. Most athletes stayed in dorms at the University of Chicago and a nearby hotel, but some were housed at Lake Forest College and North Central College.

The United States won 122 gold medals, followed by Argentina with nine, Brazil with eight, Canada with seven, and Mexico with six. The extreme disparity in medals may have contributed to lack of interest in the Games, lopsided as they were. Foreign athletes and delegations also complained about the organization and execution of the events. “When you have an event with a lot of people and nothing working right, then the competition takes place, and that’s what saves you,” said the American basketball player Oscar Robertson.

The Games closed on September 7. The next day, a 26-year-old Brazilian rower was found shot dead on a lawn at North Central College, providing a shocking—and distracting—end to the Games. The murder was never solved.

In the end, Chicago’s 1959 Pan-American Games were mediocre at best. The things that distinguish them—the disbursal of federal money and a murder—were not positives. Thus Chicago has become “defensively indifferent” to the Games, in the words of MacAloon, and forgotten them. As Tokyo takes on the delayed Olympics this month in the midst of a global pandemic, rising infection rates in Japan, and homegrown opposition, Chicago’s experience with its own problem-plagued Games might provide a warning.