Why America Is the Only Country That Embraced the Lie Detector—and Chicago’s Role in Its Rise

Daniel Hautzinger

January 3, 2023

American Experience—The Lie Detector premieres Tuesday, January 3 at 9:00 pm and will be available to stream the same day.

The lie detector has been used in the United States to elicit confessions of crimes (even though it is banned from court except in very specific circumstances); to probe the veracity of government workers or potential employees at everything from banks to gas stations (but it is fallible and can cause people to fail simply because they are nervous about the test); and to test the popularity of films, razors, and more (despite one of its creators denouncing such efforts as hucksterism).

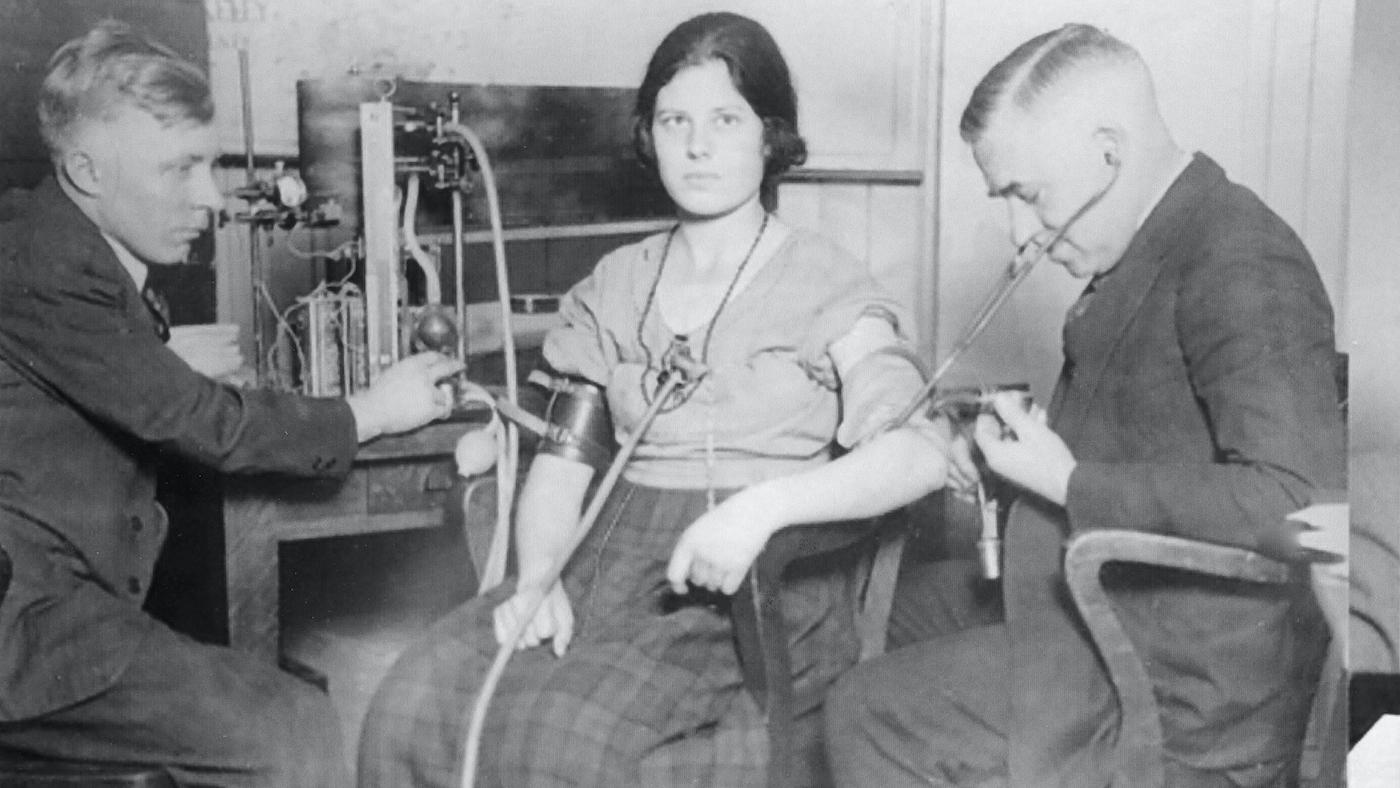

The technology—measuring heart rate, pulse, breathing, and sweat—is basic and available around the world, but only the United States uses it as a lie detector. Why?

“There are two answers, I think,” says Ken Alder, a professor of history at Northwestern University and author of the book The Lie Detectors: The History of an American Obsession. He also appears in the new American Experience documentary The Lie Detector. “One is what’s called the proximate answer, which explains why it gets started in the United States, and that’s because of police reform.”

The device that eventually became the lie detector was developed by John Larson, a policeman with a Ph.D. in physiology. Larson had been tasked with creating a machine that could determine if someone was lying by August Vollmer, the Chief of the Berkeley Police Department in California at the time, and the “father of police reform in the United States,” according to Alder.

“The idea for the lie detector was that it would be a way to constrain the police themselves,” Alder says. At the time, in the early 1920s, it was common for police in America to obtain confessions via what was known as the “third degree”: torturing or beating up suspects in interrogation. The lie detector “would be a more humane kind of third degree,” Alder explains.

“The United States police are unique in being so municipal and connected to local governments, and not—at least initially—subject to the same national standards or civil service requirements and not having the same sort of state-enforced disciplinary tools as the police in Britain or France or other countries,” Alder says. “So the police in the United States were notably corrupt.” The lie detector seemed like a tool of reform.

“The other, bigger answer to why [the lie detector became popular in] the United States is that the lie detector fits into a pattern that the United States is a particularly good example of,” Alder says. That is, “Using tools that are scientific and have this allure of objectivity to solve contentious social problems.” He points to another creation of the era, the IQ test and its successors such as the SAT, as a similar example.

Both the IQ test and the lie detector are “seemingly objective,” in that a machine can do the grading or lie detection, and “the machine seems fair,” as Alder puts it. But in both cases, “How you frame the questions matters a lot.” And with the lie detector, while the machine seems to be making the judgment, it is in fact the operator who does so, by asking the questions and interpreting the machine. “In fact, the operator often will accuse the suspect of having failed the test,” Alder says. “That way, the subject can be sort of tricked into confessing.”

John Larson, the original inventor of the instrument that became the lie detector, was wary of such an approach and became skeptical of the use of the lie detector in acquiring confessions. He came to Chicago in the early 1930s to work at the Institute for Juvenile Research, where he used the lie detector “as a way of probing the psyche of young people to try to get at their guilt complexes,” as Alder puts it. “It’s a very different, much less coercive use of the polygraph.”

It was Larson’s assistant from his days developing the lie detector who popularized it as a coercive tool. Leonarde Keeler worked with Larson as a high school student in Berkeley before eventually also ending up in Chicago to work at the Scientific Crime Detection Laboratory at Northwestern University.

The lab was set up to address Chicago’s notorious crime problem in the wake of the infamous Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre, in which seven gang members were gunned down in a garage in 1929. It was the first American scientific crime lab, and developed various forensic science techniques, including in lie detection after Keeler joined.

Keeler is largely responsible for the lie detector’s widespread adoption by police departments, as he trained policemen in its use at the Scientific Crime Detection Laboratory and convinced police departments that it was an effective tool for extracting confessions. He also consulted on cases outside the lab in a private capacity with his wife Kay, a specialist in handwriting analysis. Keeler even appeared as himself in the 1948 James Stewart film noir Call Northside 777, which was based on a real-life Chicago case in which Keeler had helped free a man wrongly convicted of murder. (The portrayal of lie detectors in popular culture as powerful tools explains much of their staying power as well as misperceptions of their actual efficacy and abilities.)

In addition to Larson and Keeler, there was another man integral to the story of the lie detector: the lawyer and psychologist William Moulton Marston. He touted a method of lie detection based simply on observing blood pressure. A penchant for salesmanship and outlandish claims led him to try to use lie detectors everywhere from Hollywood to Madison Avenue.

He needed to find new ways to make money so frequently in part because of his unconventional life: he lived in a polyamorous relationship with his wife and a former female student. Despite his involvement with the lie detector, Marston is most famous for a different creation: Wonder Woman, with her Lasso of Truth.

“These three different guys, they do represent different ways that we have looked to science to solve social problems,” Alder says.

“These machines operate differently in very different social contexts,” he says. “Tools are not neutral. They do have properties that encourage one kind of use maybe over another, but they’re flexible tools, and they can be used in lots of different ways.”

“One way to think of the lie detector is as a kind of placebo test,” he continues. “In itself, it doesn’t do much, but it’s what we think it does that allows it to have its power. In a way, it’s a measure of our belief in science itself.”

Not that the lie detector is an example of how specialized science actually works in discovering facts—but that’s beside the point in this popular desire to believe in the objectivity of science and machines.

As Alder says, “What exactly is meant by science is in some sense less important than this desire to believe in the thing, that there is an answer out there, and that this mysterious thing called science can supply it.”