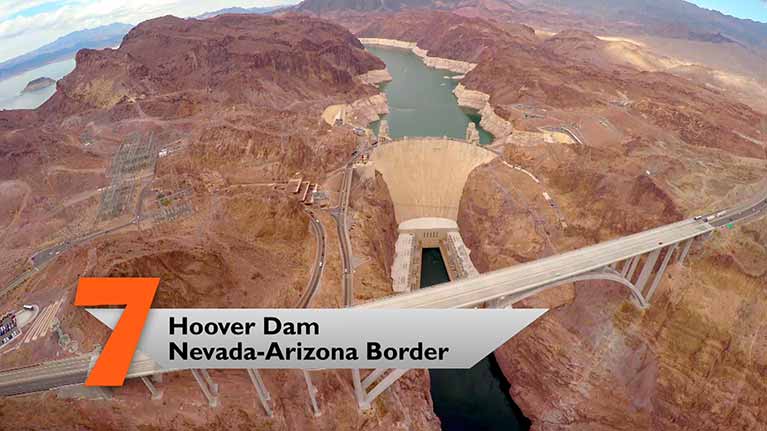

Hoover Dam

Hoover Dam

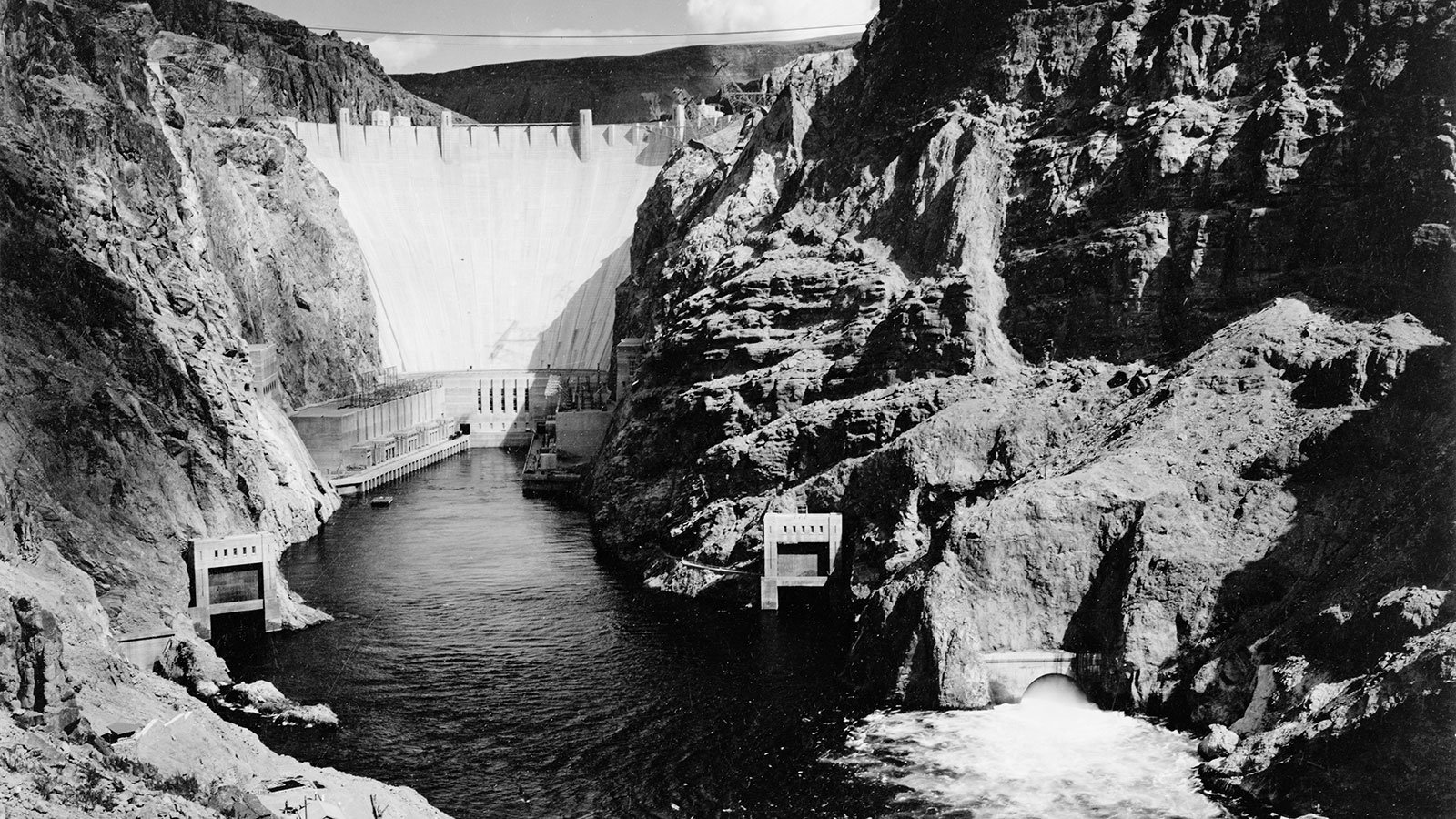

It was designed to do the impossible: stop the mighty Colorado River dead in its tracks and provide water and power for the growing cities of Southern California. The dam also employed thousands in the midst of the Great Depression.

The Hoover Dam was designed to do something that appeared impossible at the time: stop the mighty Colorado River dead in its tracks.

Architectural historian Reed Kroloff calls it “one of the most remarkable feats of human engineering and hubris anywhere ever.”

“This isn’t any river. This is the river that made the Grand Canyon,” he said.

The mighty Colorado was an extremely valuable resource in America’s bone-dry western states. A dam running across it could create a massive reservoir and a consistent water supply. It would also help tame the river, which had broken through an irrigation canal in 1905, creating an entire inland sea. And of course, it had the potential to generate enough power for nearby Las Vegas, which was experiencing a population boom in the 1920s.

But damming the powerful Colorado River was easier said than done. It would take a 70-story dam, taller than any the world had yet seen. And it would take six companies to pull it off.

“It’s so big that when the bidding was done, there was not one company that could build it,” explained Michael Green, an associate professor of history at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “It took six companies, which incorporate themselves with the highly creative name of ‘Six Companies.’”

Congress approved the project and appropriated funds in 1928, just before the country descended into the Great Depression. By the time construction began, thousands of men, many with their families, had already flocked to the desert surrounding the jobsite, desperate for work. The federal government had plans for a model city that would house the workers and their families – Boulder City, Nevada. But it wasn’t ready in time for their arrival. So when potential workers arrived from all over the country, they landed in Las Vegas, then just a town of approximately 5,000 people, as well as a series of squatters’ camps closer to the site.

“First they have barracks,” said Green. Then, after Boulder City was completed in 1931 and workers began moving there, living conditions improved.

“They have houses that tend all to look the same,” said Green, “to the point that there were workers who came home late at night who might walk into the wrong house – which caused a bit of an uproar now and then.”

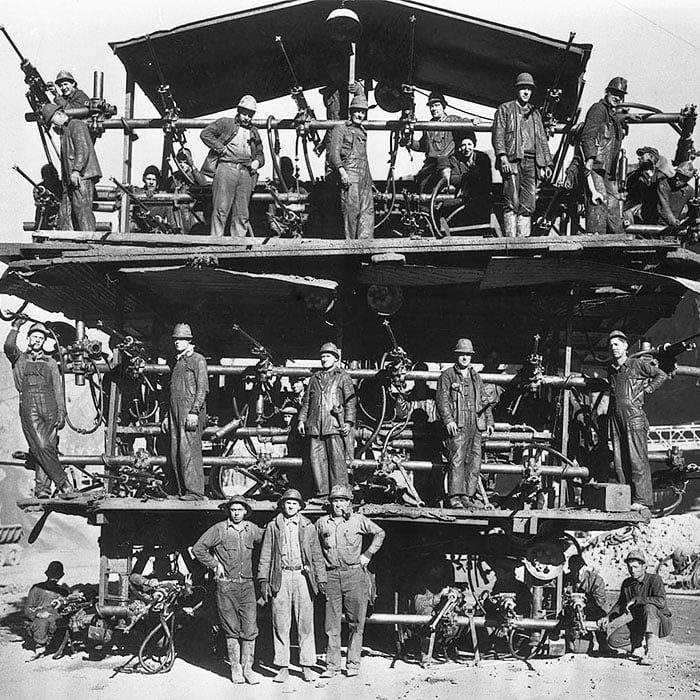

More than 5,000 men worked on the project at peak employment in the summer of 1932, and more than 20,000 worked there over the life of the project, most of them in jobs that paid modestly well for the time. Almost all of the workers were white, with the exception of a small, segregated black crew and a number of Native Americans who did specialized work.

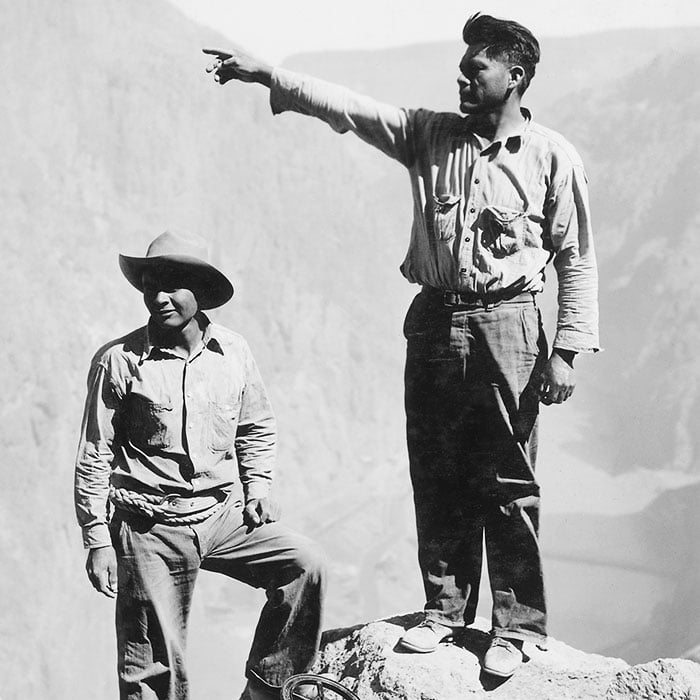

Their boss was a taskmaster named Frank Crowe. He pushed workers around the clock, at times through 120-degree heat.

“Crowe is always around here making them work faster,” said Green. “Their nickname for him is ‘Hurry-up Crowe.’ That’s not a nickname for somebody they love.”

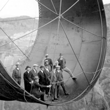

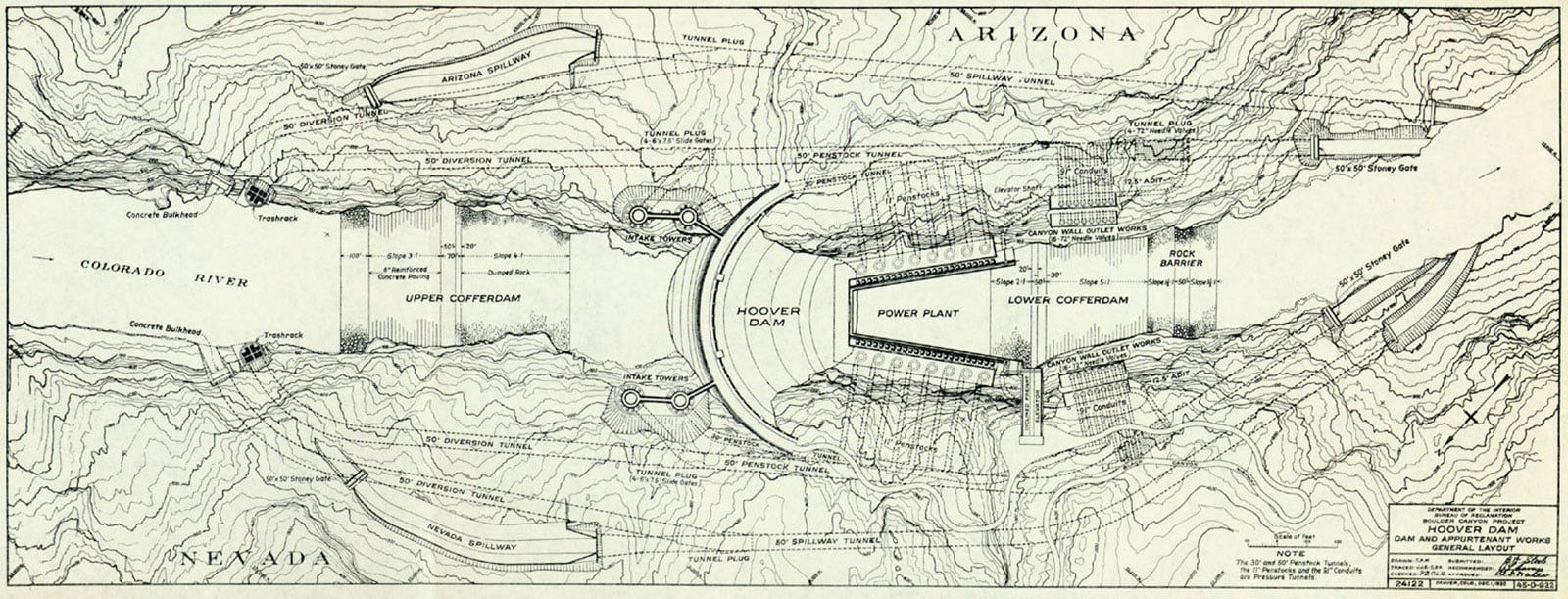

The first order of business was to move the river to make way for construction. This required four 50-foot diversion tunnels on either side of the canyon. Since the Colorado River forms the border at the site between Nevada and Arizona, there were two tunnels constructed in each state.

Inside the tunnels, the desert heat often mingled with the exhaust from trucks and machines, creating a lethal stew. During one particularly brutal summer, one worker died as often as every other day.

By 1932, the two tunnels were complete, cofferdams were built to facilitate the diversion, and the Colorado River changed course.

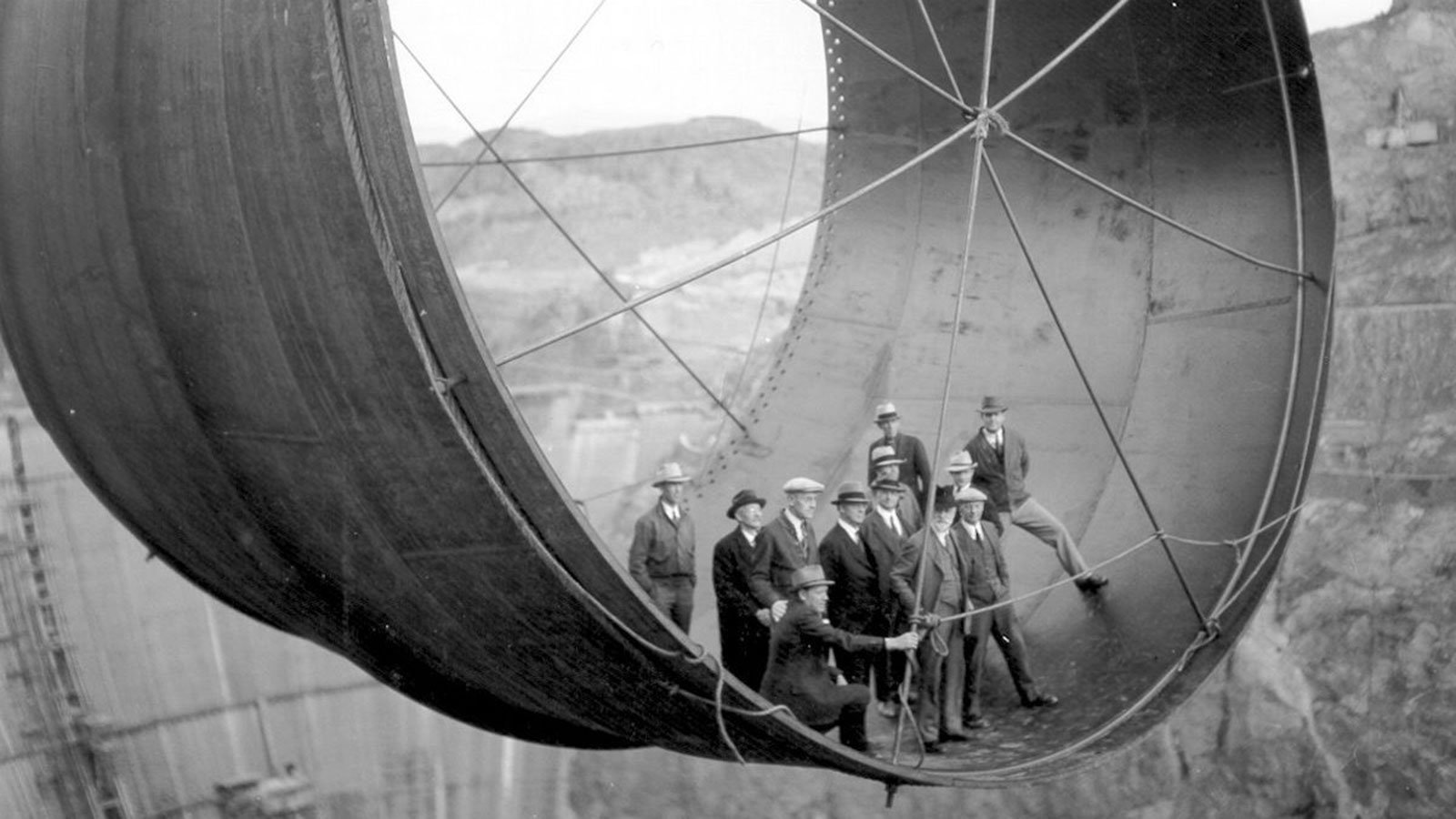

Next, workers needed to make sure that the canyon walls were sound enough to anchor a massive dam. Workers called “high scalers” were lowered over the canyon rim in safety belts or boatswain chairs. Suspended as much as 800 feet in the air, they chipped away at loose rock with 44-pound jackhammers, metal poles, and dynamite.

“They are coming down on cables and planting dynamite and swinging back, ideally, so that they don’t get blown up,” said Green. “I wouldn’t call them necessarily the elite, but they’re sort of the spidermen. These are the acrobats, these are the people who have the superhuman power, if you will, to come down, plant [dynamite]… and get out of the way and make room for that dam.”

But not all of them did manage to get out of the way. Many of the jobs on the site were deadly. The official number of “industrial fatalities,” meaning on-site deaths that were directly attributable to the work being done, is 96. That number includes deaths from falling off canyon walls, being crushed by falling rocks or heavy equipment, and being run over by trucks, among other things. At least another 16 died from the heat, and more than 40 died from pneumonia, deaths that some workers’ families claimed were actually caused by carbon monoxide poisoning. The misclassification, they say, was a tactic used to avoid paying compensation.

The official death toll also does not include the very first fatalities connected to the dam: those of Bureau of Reclamation surveyors J. G. Tierney and Harold Connelly, who fell into the Colorado River and drowned in 1922 while surveying the site. In an eerie coincidence, the last official “industrial fatality” on the site was Tierney’s son, Patrick W. Tierney, who fell from an intake tower and died on December 20, 1935.

Contrary to popular myth, no workers’ bodies were trapped in the concrete.

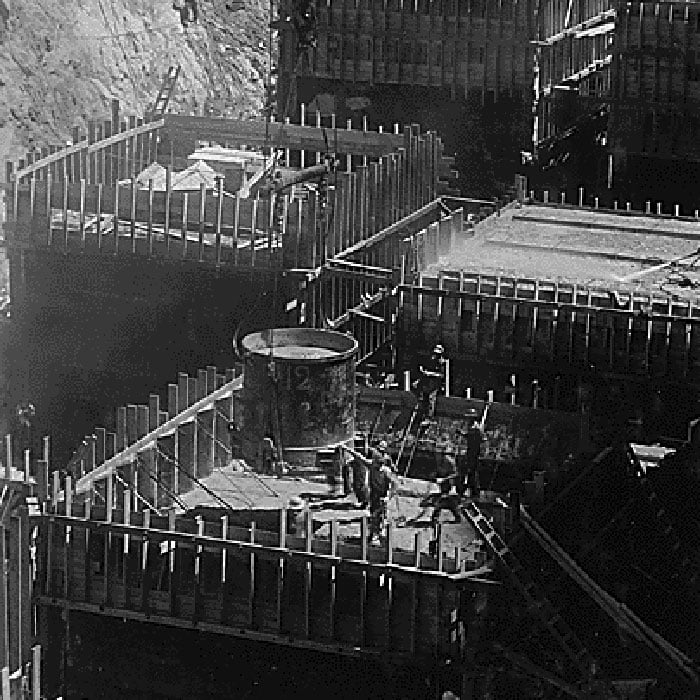

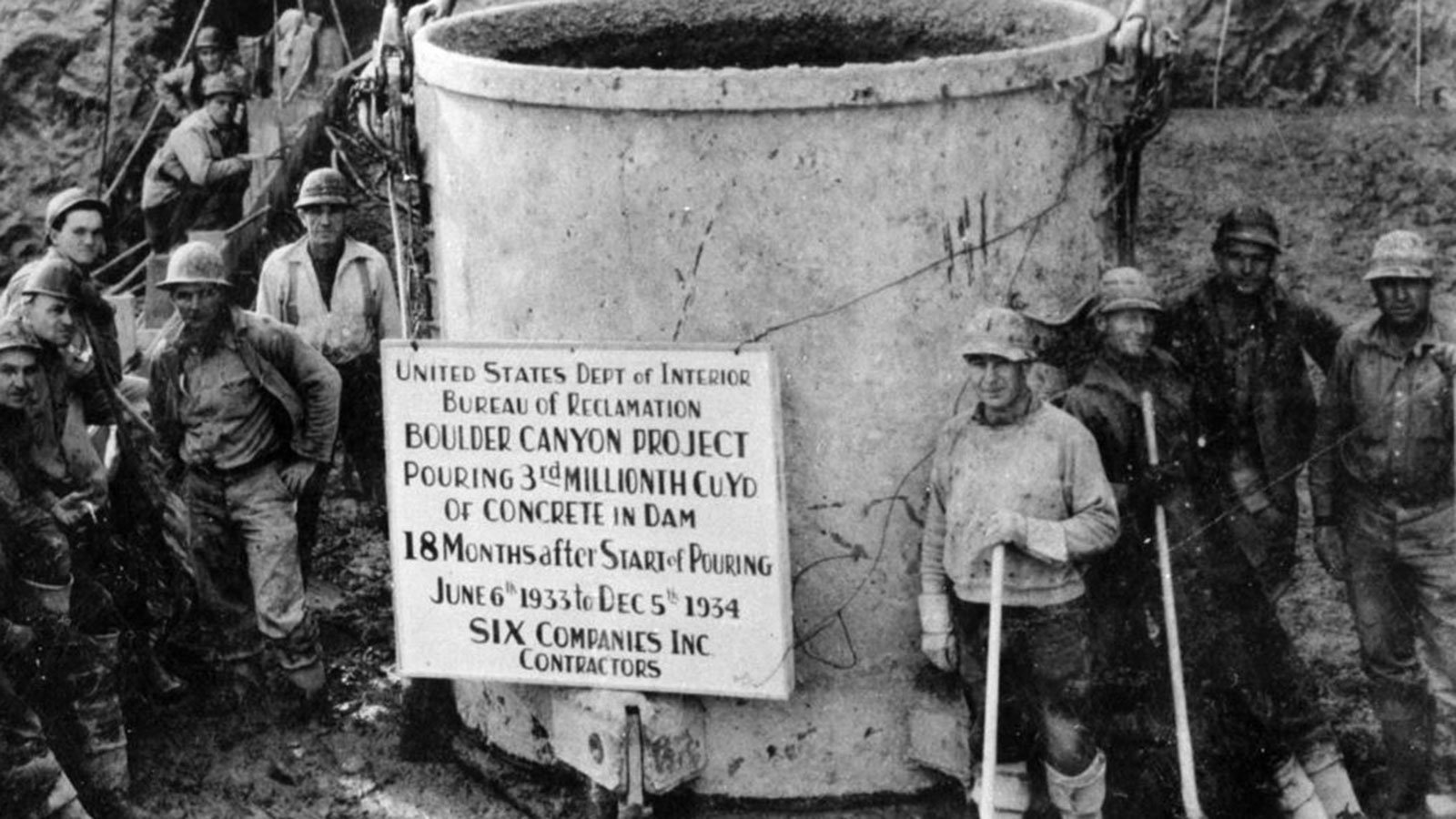

But a tremendous amount of concrete was poured to build the Hoover Dam: enough to build a sidewalk around the Earth. They poured it into a series of individual trapezoidal blocks so that the blocks could cool more quickly. According to calculations done by Bureau of Reclamation engineers, if the dam had been built in one, single, continuous pour, it would have taken a full 125 years for the concrete to cool and harden.

It took nearly two years, working around the clock, to lay the concrete blocks.

After the dam was assembled, workers filled the diversion tunnels with concrete plugs, and what is now Lake Mead began to fill behind the dam, held back by the weight of the dam’s concrete and the strength of its arch. At the time, the Hoover Dam was the largest hydroelectric installation in the world.

Today, it holds seventeen turbines, all of which are powered by Lake Mead’s waters.

The Hoover Dam made it possible for a city like Las Vegas, with all of its neon lights, to be created in the middle of a desert. And not just Vegas – the entire region, reaching from the shores of San Diego, California, to the hills of Tucson, Arizona, has been able to grow and thrive.

Today, the dam generates electricity for an estimated 1.3 million customers in Nevada, California, and Arizona. And although recent droughts and water consumption trends have caused its levels to drop to record lows, Lake Mead still provides water to an estimated 25 million people.

Green calls the Hoover Dam a “precedent-setting dam.” It inspired the construction of more dams – especially in the Tennessee Valley. And it proved to the world that even the mightiest river can be tamed.

![[Native Americans] employed on the construction of Hoover Dam as high scalers](http://interactive.wttw.com/sites/default/files/Marvels_7-HovDam_Workers01_1932_BoR.jpg)