Located on Chicago’s South Side, the Bridgeport neighborhood was once an enclave of Irish immigrants and, later, Germans, Poles, and Lithuanians. It also was once a political pipeline for Chicago’s powerful Democratic machine: Five of the city’s 57 mayors, serving terms that spanned from 1933 to 2011, came from Bridgeport.

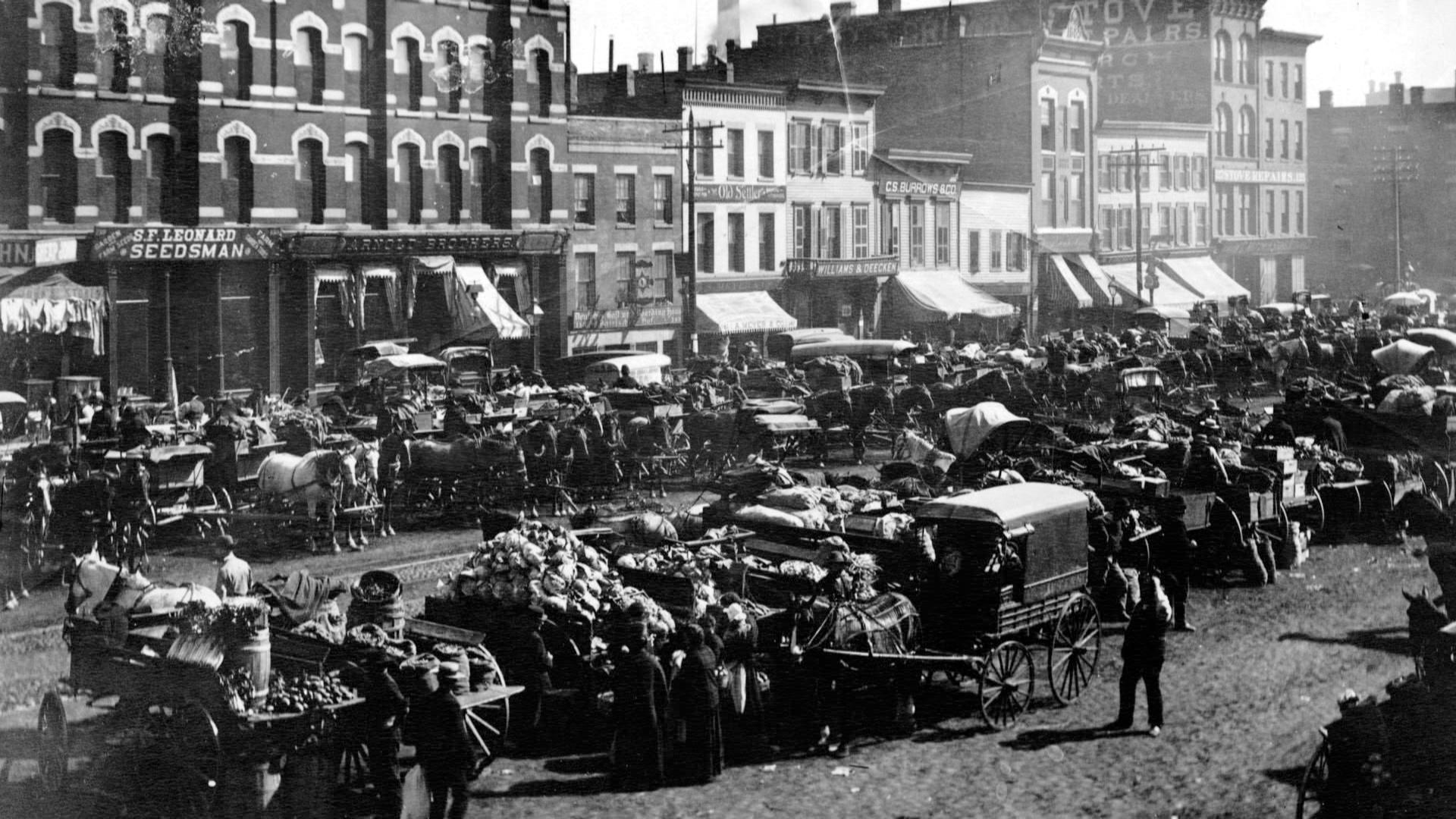

Chicago Stories: The Union Stockyards

At the end of the 19th century, Chicago completely transformed the way Americans eat, and the Union Stockyards on the South Side were the center of that revolution. Experience the sights, sounds, and awful smells of the Union Stockyards and the complex of meat factories next to it, known as Packingtown.

Go deeperA mostly blue-collar community, Bridgeport sat near the edge of the Union Stockyards. Its political history began with the Irish immigrants who settled in Chicago in the mid-19th century after fleeing famine and political conflict in England.

“Coming out of Ireland, which is the first colony of the United Kingdom, they know how democracy works, and they know how it doesn’t work for them because they’re kept out of the British system. And they want to make sure that they’re kept in the system here,” Chicago historian Dominic Pacyga said.

Many Irish Chicagoans got involved in local politics, and other immigrant groups followed suit. Ethnic tension and conflict was common in the neighborhood.

“It was a hard neighborhood, but it was also one of those neighborhoods where the important things were God, family, and work,” Chicago journalist and author Rick Kogan told Chicago Stories. “Bridgeport you could consider the birthplace of mayors.”

Meet those mayors below.

Edward J. Kelley

Born to an Irish and German family in 1876, Edward Joseph Kelly was the first in a series of mayors that hailed from Bridgeport. Before serving as mayor, he was the chief engineer at the Chicago Sanitary District. He was also the head of the South Park Commission, which was originally created to shepherd the development of some parks on the South Side. As head of that group, he oversaw the opening of Soldier Field (which was first, although briefly, called Municipal Grant Park Stadium).

Kelly became mayor in 1933, following the assassination of his predecessor, Anton Cermak, who was killed by a bullet meant for President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Kelly was backed by then-chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party and big political boss Patrick Nash. Kelly is credited with keeping the city above water during the Great Depression. But according to one examination by the University of Illinois Chicago, Kelly also garnered a similar reputation as Mayor “Big Bill” Thompson – in other words, playing fast and loose with ethics. Kelly also had more progressive views regarding race than the other leaders in his own Democratic machine, which hurried him out the door, per Paul Green in the Encyclopedia of Chicago. Kelly served four terms until 1947, when the machine handpicked the next mayor.

Martin Kennelly

Martin Kennelly was the machine’s next choice for Chicago mayor. Kennelly was another Irish Catholic born in Bridgeport in 1887. He grew up in a family of modest means, served in World War I, led the Chicago Red Cross, and later became a successful businessman.

Kennelly assumed office in 1947, serving two terms in the post-war era and into the 1950s. He also kick-started the slum-clearance process that Richard J. Daley would accelerate. Kennelly was not a loyal cog in the Democratic machine, however, and enjoyed some popularity among Republican voters. That would cost him. Because Chicago still had partisan municipal elections at the time, some of his supporters couldn’t vote for him in the Democratic primary, according to UIC’s Kennelly papers. In 1953, Daley had become chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party. Daley had the party’s support when he ran against Kennelly in the 1955 primary and defeated him.

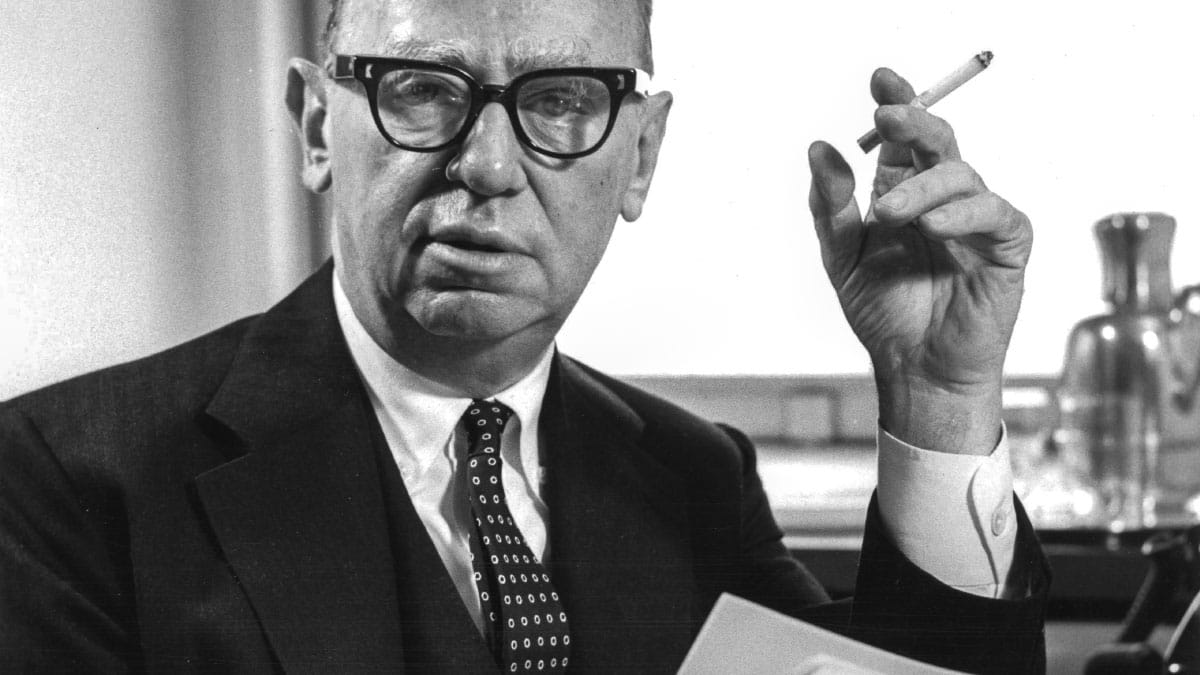

Richard J. Daley

Daley may not have created the Chicago Democratic machine, but he certainly fine-tuned it. Born in 1902 and raised in Bridgeport, Daley was an only child born to Irish Catholic parents. His father was a sheet metal worker, and his mother was a homemaker. Growing up, he was part of, then later president of the Hamburg Athletic Club, a social, athletic, and political organization where a young Daley began to make his mark. Though there was no evidence he was ever involved, some members of the club were associated with the violence against Black Chicagoans amid the 1919 race riots.

When the Democratic Party Was Torn Apart

The Democratic National Convention of August, 1968, held in Chicago, was a defining moment of the Vietnam era and a watershed in American politics. What actually happened during that devastating event that pitted police against protesters and ripped apart the Democratic Party?

Go deeperDaley worked his way up through state and local politics, becoming mayor in 1955. As both mayor and leader of the party, Daley had a strong grip on Chicago politics, crafting a well-oiled system of patronage in which wards were given an allotment of jobs in exchange for loyalty to the city’s Democratic organization. In his nearly six terms as mayor, Daley pushed projects that reshaped Chicago and created a more modern city, but in the process exacerbated the segregation of neighborhoods along racial boundaries. His administration went on a years-long building spree that expanded the city’s skyline, with such buildings as Marina City, Hancock Tower, Sears Tower (now Willis), IBM Plaza (now AMA Plaza), and Lake Point Towers.

Daley also grew the city’s public works projects to clean up the city and expanded the Chicago Police Department force. But with the expanded police force came more controversy. He ordered officers to “shoot to kill any arsonist or anyone with a Molotov cocktail in his hand” during the 1968 riots following the death of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. That same year, Daley’s police force was once again criticized for its excessive violence against protestors at the Democratic National Convention.

In 1976, Daley died while still in office, partway through his sixth term.

Michael Bilandic

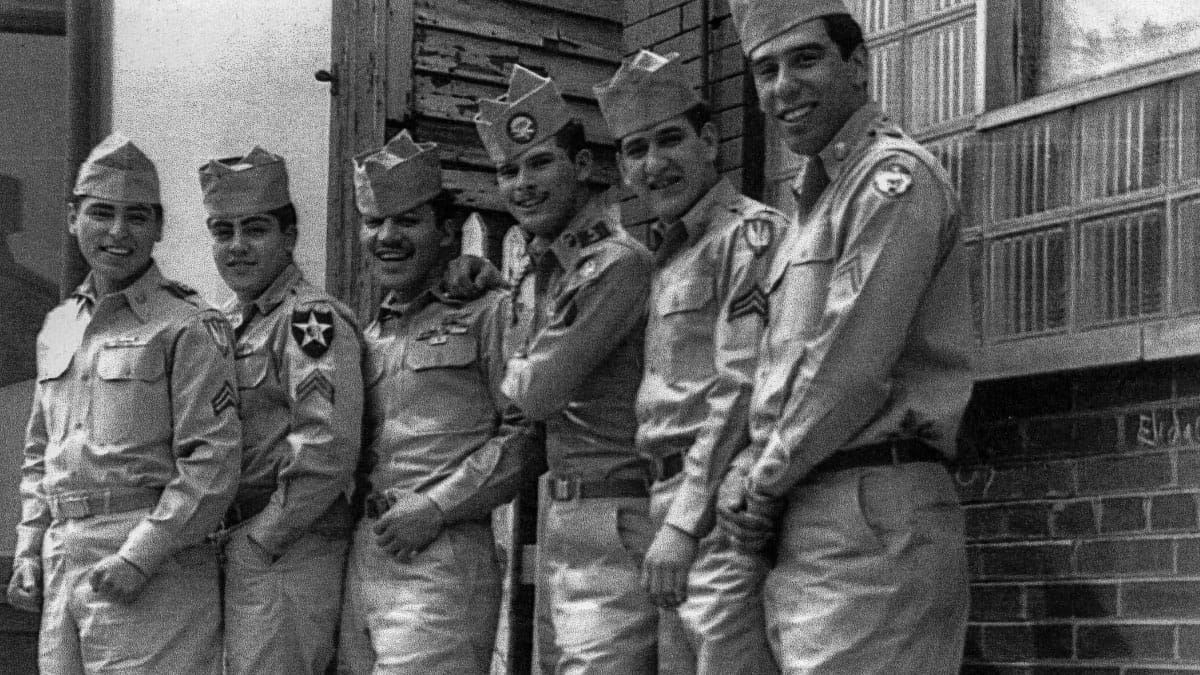

Following Mayor Daley’s unexpected death, Michael A. Bilandic was appointed mayor. Bilandic was born to Croatian immigrant parents in Chicago, served in World War II, and was a graduate of DePaul University’s law school. Before he was mayor, he was alderman of the 11th Ward, which includes Bridgeport.

Bilandic’s appointment as mayor was not without controversy. According to the city’s line of succession, the president pro-tem of the City Council – a Black alderman named Wilson Frost – should have been the person to take over as mayor. But Daley’s aides locked Frost out of the mayor’s office. After some behind-closed-doors dealmaking, the City Council did not approve him, instead naming Bilandic mayor.

Chicago Stories: Jane Byrne

Jane Byrne's unexpected entry into politics led her to rise through the ranks under the mentorship of Richard J. Daley. Despite her loyalty to the political machine, she later exposed corruption, suffered job loss, and embraced an anti-machine stance in her 1979 mayoral campaign. Her journey culminated in her historic achievement as Chicago's first female mayor.

Go deeperPart of the deal with the machine was that Bilandic’s time as mayor would be temporary and that he would not run in the 1977 special election. He did anyway, and he won. He was not seen as quite the strongman that his predecessor was, with Chicago columnist Mike Royko nicknaming him “Mayor Bland,” according to Bilandic’s New York Times obituary.

Bilandic got into political trouble with the person who would later unseat him: Jane Byrne. Bilandic and the Democrats removed Byrne, a Daley protégée, from her job as co-chair of the Cook County Democratic Central Committee. Then, in 1977, Bilandic fired her from her position with the city’s consumer affairs department after she publicly accused him and other city officials of approving an illegal 12% taxi-fare increase in a backroom deal. Byrne challenged Bilandic in the primary and stunned the city with her victory. Her victory was also aided, in part, by Bilandic’s botched handling of the 1979 snowstorm, during which he had CTA trains run express to supposedly keep things moving, bypassing Black neighborhoods in the process.

The end of his mayoralty was not the end of his career. Bilandic went on to serve as a justice on the Illinois Supreme Court, eventually serving as chief justice.

Richard M. Daley

Richard M. Daley, the son of Richard J., served 22 years as mayor — beating his father’s record by one year. Born in Bridgeport, the younger Daley was the fourth of seven children and the oldest boy. He followed a trajectory similar to that of his father, working his way up through state and local government positions, as well as in roles within the Democratic Party.

A Comedy of Errors: How a Small Leak Became the Great Loop Flood of 1992

In April 1992, an unusual underground flood in Chicago's Loop went unnoticed by commuters, but it turned into a costly two-week saga, costing nearly $2 billion. It submerged building basements, disrupted lives, and created unexpected heroes, ultimately serving as a reminder to pay attention to forgotten things, even the obscure tunnels beneath our daily commute.

Go deeperDaley first became mayor in 1989 in what was a special election for the remaining two years of Harold Washington’s term after Washington died while in office. But that wasn’t the first time he had run for mayor. In 1982, Daley ran in the Democratic primary against incumbent Jane Byrne and Washington, who ultimately won to become the city’s first Black mayor.

As mayor, Daley tore down some of the failed housing projects built during his father’s administration. He was the first mayor to appear in the Chicago Pride Parade while serving in that office and later expressed support for same-sex marriage. He also pursued policies that would turn Chicago into a tourist destination, as he oversaw the revamping of Navy Pier and the construction of Millennium Park. He also had to contend with the 1992 Loop flood, which saw some downtown buildings flooded after a breach in a forgotten tunnel system.

Daley certainly had his headaches, too. Some AIDS activists believed Daley didn’t act quickly enough when the epidemic hit Chicago hard. He controversially had Meigs Field secretly destroyed overnight without consulting officials. He also committed the city to long-term leases that essentially privatized certain public services for a cash influx, such as the much-maligned 2008 parking meter deal in which the city got $1.15 billion in the short term, but ceded 75 years’ worth of parking meter revenue to privately run Chicago Parking Meters, LLC.

Daley left office in 2011 after serving his sixth and final term.