Fourteen Remarkable Libraries in the Chicago Area

Geoffrey Baer

February 7, 2024

Last year, I featured the dazzling Tiffany mosaic-encrusted and stained glass-domed Cultural Center for my The Most Beautiful Places in Chicago. The building was originally the Central Library of the Chicago Public Library, which celebrated its 150th anniversary last year. Designed by the architects behind the nearby Art Institute of Chicago, it was a big step up from the CPL’s first home in a decommissioned water tank.

Over the more than a century since that Central Library opened in 1897, plenty of other remarkable libraries have been constructed in the Chicago area, their engaging architecture reflecting the wonder of the books and other media contained within. The newest, the Obama Presidential Center, is currently – controversially – rising in Jackson Park and scheduled to open in 2025.

Here’s a whirlwind tour from across the Chicago area.

Newberry Library

The Newberry Library on the Near North Side actually predates the Central Library/Cultural Center, although not the CPL itself. Established by a provision in the will of the businessman Walter L. Newberry, its collection now spans 27.5 miles of shelving, according to the institution. Henry Ives Cobb – who designed many buildings at the University of Chicago – was the architect of its ornate building, which was finished in 1893. Chicago architect Harry Weese contributed an addition in 1981.

A notable feature of the Newberry is actually outside it: Washington Square Park, which it faces, was once known as “bughouse square” because of the speakers who would congregate there to debate radical ideas.

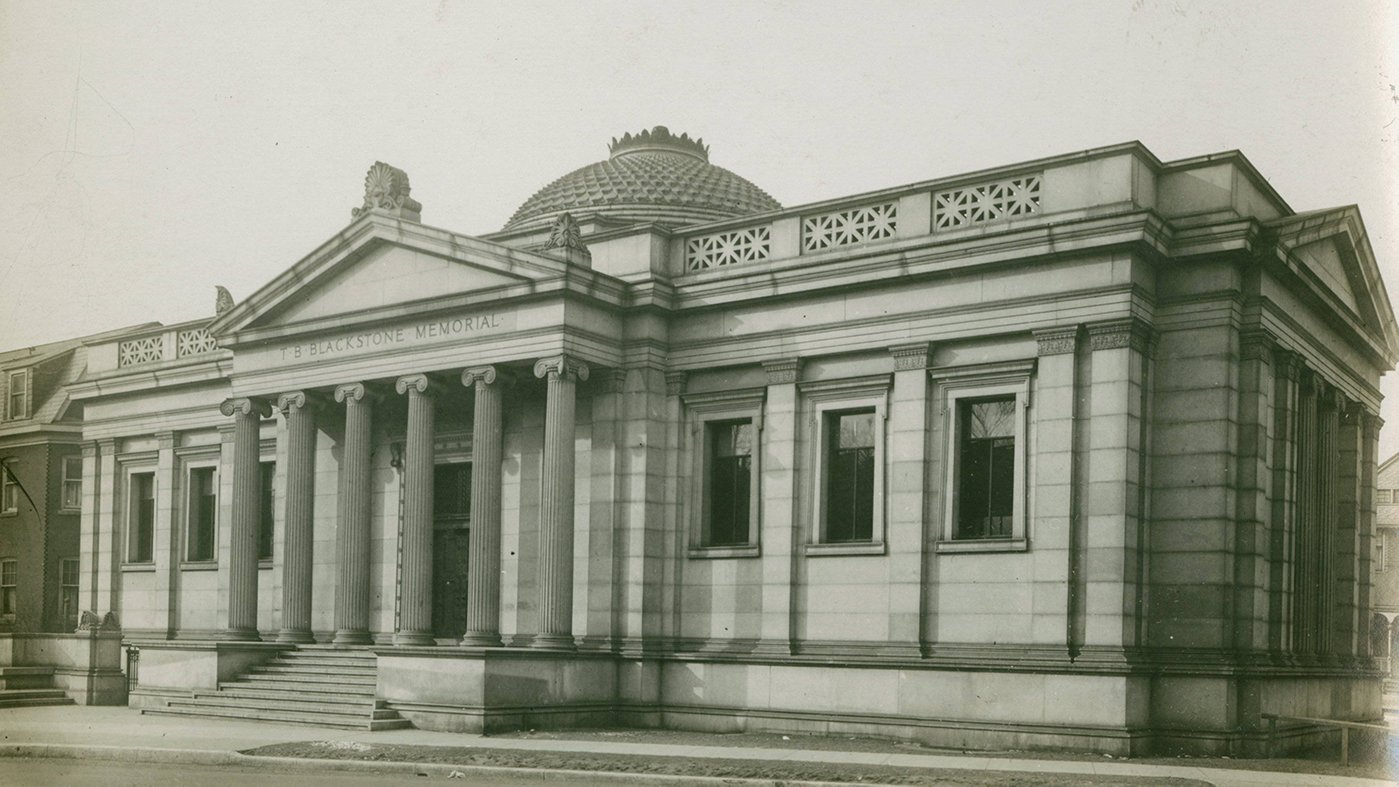

Blackstone Branch of the Chicago Public Library

Before this first branch of the Chicago Public Library opened in Kenwood in 1904, library books reached the neighborhoods via horse-drawn carriage deliveries, or a patron had to go downtown to the Central Library. The Neo-Classical building, resplendent with stained glass, mosaic tile, and mahogany, was by Solon Beman, who modeled it after a building he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. (Beman was also the architect behind Pullman.)

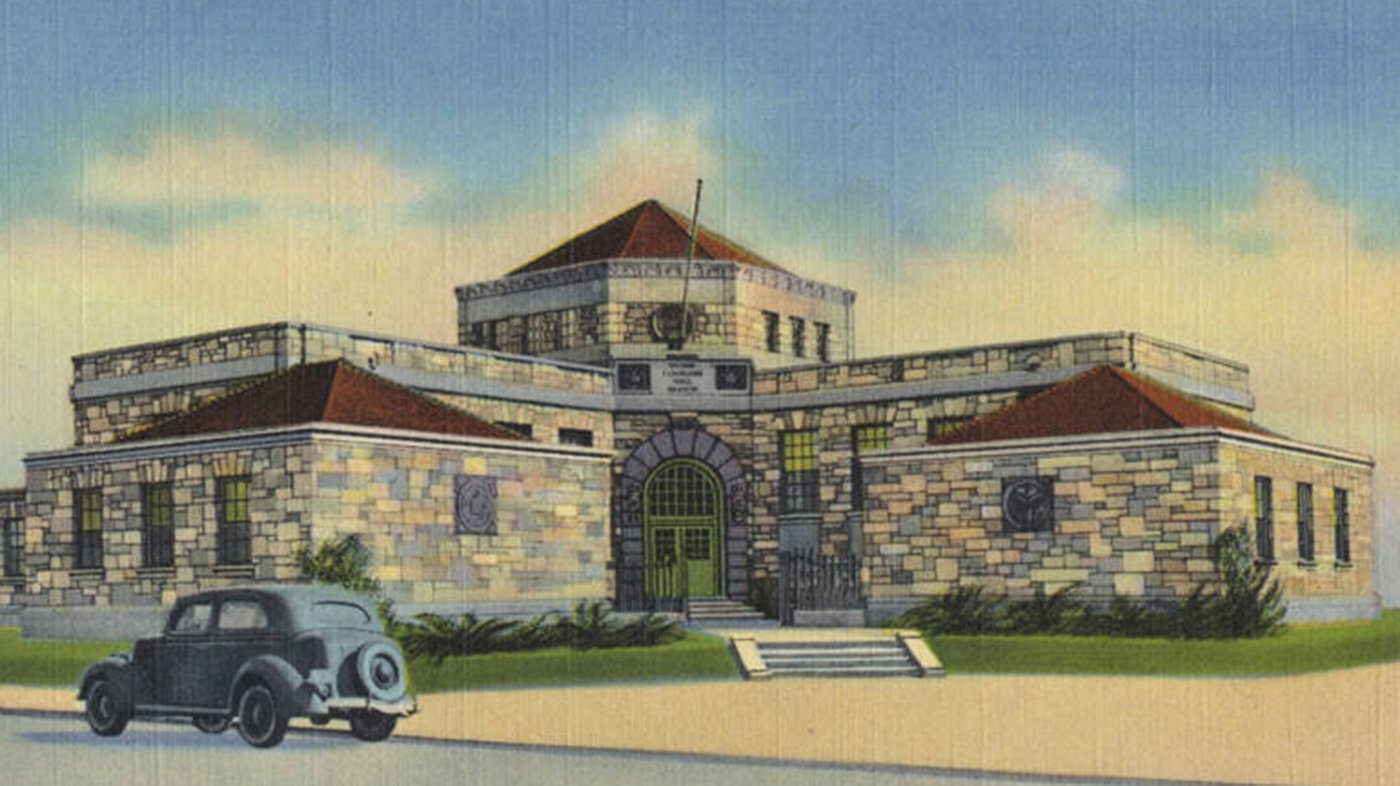

Carnegie Libraries

Around the turn of the 20th century the steel baron Andrew Carnegie began donating funds to towns across the world to finance the construction of libraries – 2,509 of them in all. Local governments were required to maintain the libraries, but otherwise there were few strings attached. The libraries were built in a variety of architectural styles, but many reflect a sense of grandeur – some are like little classical temples.

One hundred and six libraries funded by Carnegie were built in Illinois, including in the suburbs of Aurora, Chicago Heights, Evanston, Harvey, Wilmette, and more. While many are no longer standing, you can still find some that continue to operate as libraries, such as in Maywood or in northwest Indiana’s East Chicago.

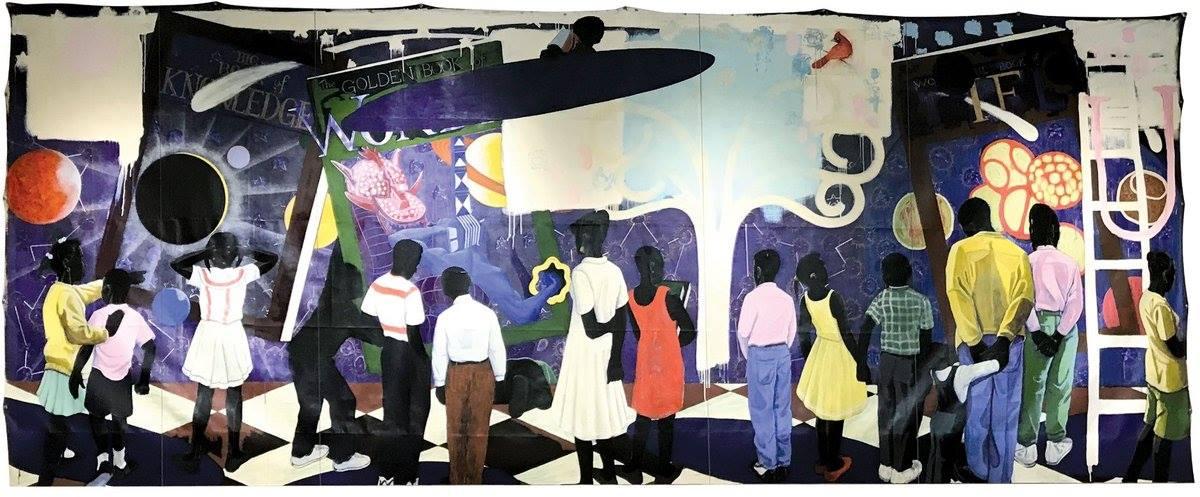

Legler Regional Branch of the Chicago Public Library

The contents of a library are typically priceless, but Legler in Garfield Park contains one thing worth a whole lot of money. The mural “Knowledge and Wonder” was painted by the now-world-famous Chicago artist Kerry James Marshall in 1995 for $10,000. When then-mayor Rahm Emanuel devised a plan to sell it in 2018 to fund an expansion of the library, it was expected to bring in more than $10 million before the sale was dropped in the face of opposition, including from Marshall himself.

Now the artist Alexandra Antoine is in residence at the elegant library, which opened in 1920 as the city’s first regional branch.

Chicago Bee Branch of the Chicago Public Library

Words were once written and published in this Bronzeville building; now they’re housed and read there. The Art Deco building was originally the headquarters of the Chicago Bee, a newspaper that primarily focused on Chicago’s Black community and at one point employed Ida B. Wells as editor. Anthony Overton, the founder of the Bee, later moved his cosmetics firm in, and eventually the CPL renovated and took over the jazzy green and white building in 1996.

Hall Branch of the Chicago Public Library

Before this branch opened in 1932, none of Chicago’s Black neighborhoods had a library. So the surgeon and community leader George Cleveland Hall persuaded the philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, a leader of Sears, Roebuck and Co. to buy and donate land to the city for a library in Bronzeville. With Vivian G. Harsh appointed as its head librarian, it also became the first library to have a Black person at the helm.

Harsh turned the branch into a gathering place for Black writers and intellectuals, hosting speakers such as Gwendolyn Brooks, Zora Neale Hurston, Alain Locke, and Richard Wright. She also built up a “Special Negro Collection” that is now housed at Woodson Regional Library in Washington Heights as the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection. With manuscripts by Langston Hughes, the archives of important Black churches, and the papers of prominent Black Chicagoans, and more, it is the largest African American history and literature collection in the Midwest, according to CPL.

Hall branch was also the home of the pioneering Black librarian Charlemae Hill Rollins, who pushed for better representation of Black people in children’s books.

Skokie Public Library

Gertrude Lempp Kerbis founded her own architecture firm in Chicago in 1967, an impressive achievement in the male-dominated world of architecture, but when she designed the modernist Skokie Public Library in the late 1950s, she was still at the heavyweight firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. She’s part of the underappreciated generation of female architects during the Mad Men era who found success and commissions despite intense bias and discrimination. Her design for the Skokie library brought in light via interior courtyards and lots of glass; it has since been added to and modernized over the decades.

You can find other distinctive libraries throughout Chicago’s suburbs, like in Harvey, where the Black-owned firm Moody Nolan designed the building. The firm Sheehan Nagle Hartray has specialized in libraries, with examples found in St. Charles, Oak Park, De Kalb, Lisle, and Bolingbrook.

Walter Netsch’s University Libraries

If you visit both the University of Chicago and Northwestern University, you might experience a bit of deja vu: both have imposing Brutalist libraries that look like futuristic temples, are attached to buildings in a vastly different style, and were even completed in the same year, 1970. That’s because both were designed by Walter Netsch of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, who had recently designed the controversial new University of Illinois at Chicago campus on the near west side.

His University Library at Northwestern connects to the Gothic Deering Library and is meant to evoke some of the older building’s details with its column-like vertical bump-outs. Its three towers are sited around a courtyard, whereas the Joseph Regenstein Library at the University of Chicago is crowded together and more conventionally shaped. Regenstein is also supposed to allude to the surrounding Gothic buildings, but its library pair is newer rather than old: Helmut Jahn’s Joe and Rika Mansueto Library, which consists of an oval glass dome suspended over several floors. It looks a bit like a blue tortoise shell resting on the lawn next to Netsch’s concrete, and is space-agey enough to have appeared in the dystopian film Divergent.

Harold Washington Library

The library that took over from what is now the Cultural Center as the main building of the Chicago Public Library generated controversy for not being more modern in its design. Architect Thomas Beeby, whom I profiled in a documentary, had already designed the Sulzer Regional Branch of CPL in Lincoln Square when he won a design competition for the Harold Washington Library in 1987 with the most traditional of the entries. The massive red brick downtown building – it was the largest circulating library in America when it was completed in 1991 – features playful exaggerations of classical features in a grand example of postmodernism. The skylit Winter Garden is like a beautiful courtyard – except it’s unexpectedly located on the top floor of the building.

Poetry Foundation

While it’s not just a library – this 2011 River North building by John Ronan also houses the Poetry Foundation’s offices – the 30,000-volume library it contains is gorgeous. You enter past a dark, perforated screen into a calming garden before reaching a light-filled, gracious interior that includes the poetry library, which is open to the public.

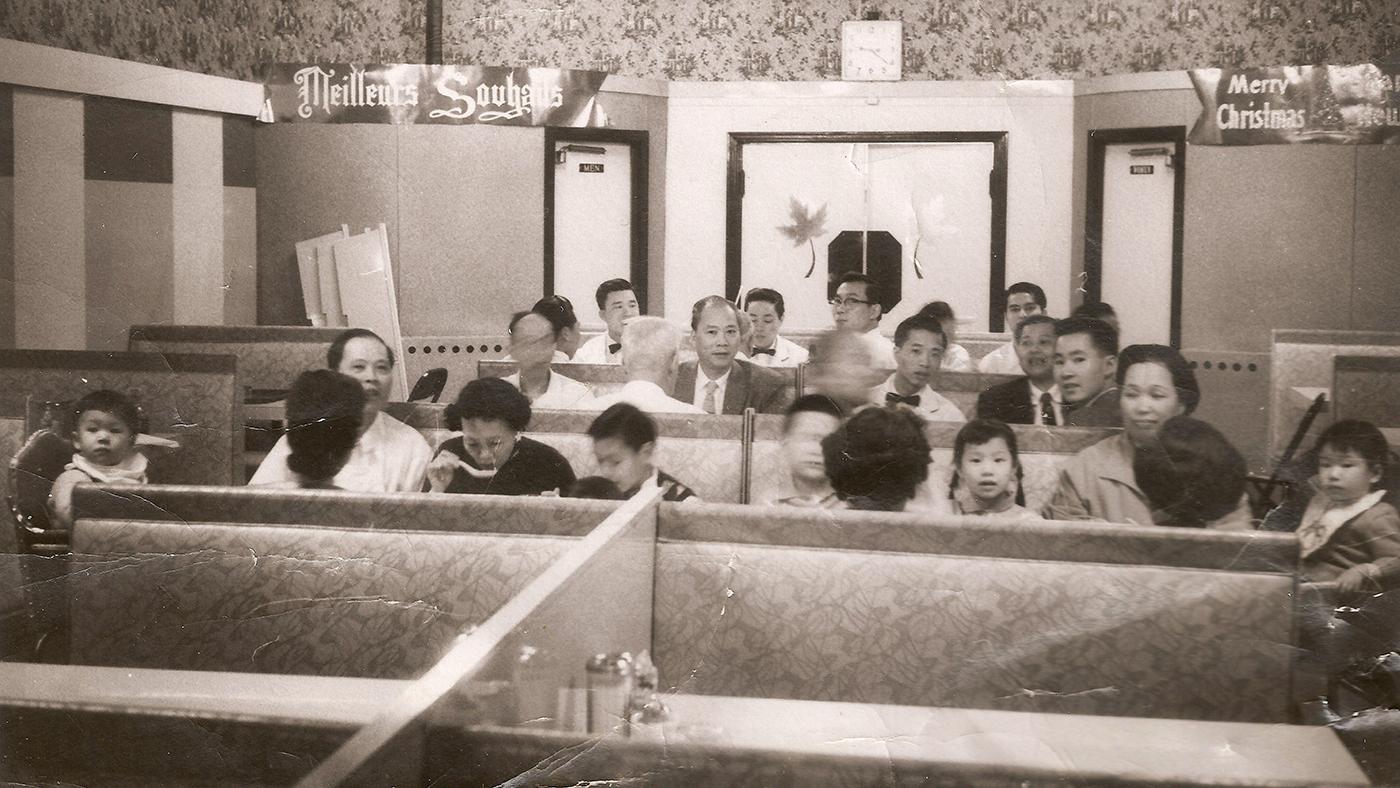

Chinatown Branch of the Chicago Public Library

Architect Brian Lee of renowned Chicago firm SOM (formerly Skidmore, Owings & Merrill) was more familiar with building skyscrapers than small, relatively low-budget public buildings when he took on the project of designing a new library for Chinatown. But his unusual creation, full of natural light and combining SOM’s modernism with traditional Chinese influences and values, has become both admired and loved in the community and the architectural world. The Chinatown library, completed in 2015, has become a defining icon of an already distinctive neighborhood. After a period when Chicago used copy-and-paste prototype plans for public buildings like libraries, it inaugurated an era of outside-the-box designs, including more by Lee himself, like the West Loop branch, which repurposed two buildings that were part of Oprah’s Harpo Studios.

Chicago Public Libraries plus public housing

Chicago has always been a wellspring of architectural innovation, and in 2019 the city opened three buildings that sought a new approach to a lack of low-income housing by combining public housing and a public library in a single building. The approach, backed by former mayor Rahm Emanuel, is called “co-location.” It allows for reduced construction costs by accessing funding for public housing to build new libraries and increasing their use in the process.

All three are exceptional buildings designed by exceptional architects. SOM’s Brian Lee echoes the neighborhood’s brick architecture in his Taylor Street Apartments and Little Italy Branch Library. John Ronan’s Independence Apartments and Branch Library in Irving Park announces itself more boldly by standing above its surrounding high-density intersection and decorating balconies and interior doors with bright colors that provide individuality to each unit. Perkins and Will’s Northtown Apartments and Branch Library in West Ridge suspends a glass-fronted box over an open entrance and also embraces color. The location of the buildings in north and near west side neighborhoods is also meant to try to integrate public housing residents into more communities.

Despite their admirable purpose, however, these three buildings only include 161 apartments, barely a drop in the bucket of the amount of housing needed – and only 97 of those are specifically public housing, as former Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin points out. “The buildings are bright, optimistic, and city enhancing,” he writes. But the headline of his piece notes, “Now we need more of these creative combinations.”

Whitney Young Branch of the Chicago Public Library

Jay Carow’s midcentury modern design for Chatham’s branch library from 1973 was opened up and integrated with the street via a redesign by bKL Architecture that opened in 2019. The welcoming glass addition increases the size of a courtyard and upgrades a lineage of black steel and glass construction in Chicago that dates back to Mies van der Rohe.

Altgeld Branch of the Chicago Public Library

I’m an admirer of Jackie Koo’s work, and this multipurpose building encompassing a library, daycare, and community space at the center of the far south side Altgeld Gardens public housing development is a good example of why. Rather than plop down a monumental building into the middle of a community, Koo’s firm designed a sinuous, amoeba-shaped brick building with numerous entrances and no obvious front or back. It welcomes everyone in, from any direction, as a library should. It opened in 2021.