Before the Blaze

In 1871, Chicago was a town on the rise.

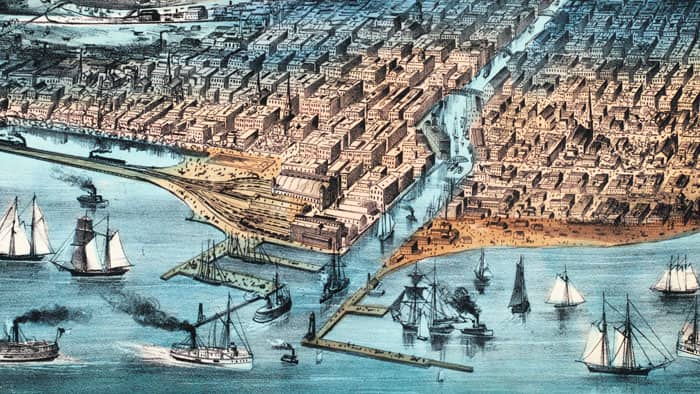

Founded in 1833 after a treaty that removed the Potawatomi people from their land, Chicago began as a modest trading post of 200 people. By 1850, the city had grown to 30,000 inhabitants. Just two decades later, before the fire that would transform the city, Chicago was a bustling hub of transportation and industry that was home to nearly 300,000 people.

The city was a perfect link between the East and West coasts; more railroads met in Chicago in the mid-nineteenth century than at any other place in the world, according to Donald L. Miller’s City of the Century, thanks in part to the rapid expansion of railroad companies owned by the city’s first mayor, William Ogden. Immigrants and East Coast elites alike flocked to the city, in search of work and fortune.

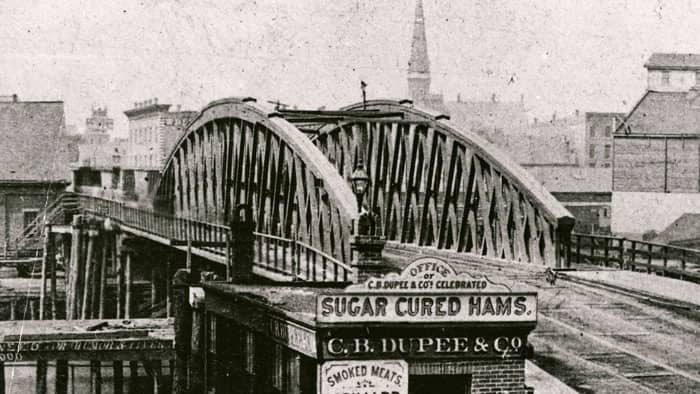

The invention of the balloon frame (a type of simple, inexpensive building framing) also aided Chicago in its rapid growth. Houses and other structures sprung up quickly, most made of wood – the perfect kindling for the fires that frequently started in the nearby dry prairielands.

As Miller writes, the city’s “hastily constructed wooden buildings, sidewalks, and bridges gave it a rough, impermanent-looking appearance, like so many other western towns of its kind.”

William Bross, a teacher from Pennsylvania who made his way to Chicago in 1848, made note of Chicago’s grimy appearance, calling it a “slab city.” Though he would go on to become a major promoter of the city and co-owner of the Chicago Tribune, Bross wasn’t impressed with what he saw when he first arrived. Pigs and vermin freely roamed the muddy, garbage-strewn streets, which lacked paved sidewalks and property drainage systems. Bross witnessed how “green and black slime would gush up between the cracks” of the wooden sidewalks. He also lamented the state of the water supply, often finding minnows “sporting in one’s wash-bowl, or dead and stuck in the faucets.”

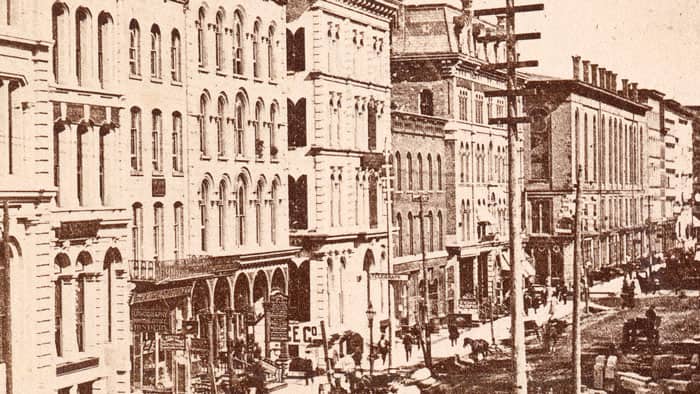

But in an attempt to keep up with other major American cities such as New York, Philadelphia, and Boston, Chicago also had ornate civic buildings such as the supposedly fireproof courthouse with its large bell tower, the Crosby Opera House, and the Palmer House hotel.

Gallery: Chicago Before the Fire

Both rich and poor walked Chicago’s less-than-idyllic streets. According to Miller, more than half of Chicago’s population in 1870 was foreign-born. The largest immigrant group was German, followed by Irish, Bohemian, and Scandinavian. In addition, approximately 3,500 Black Americans lived in what was called the South Division, south of the central business district.

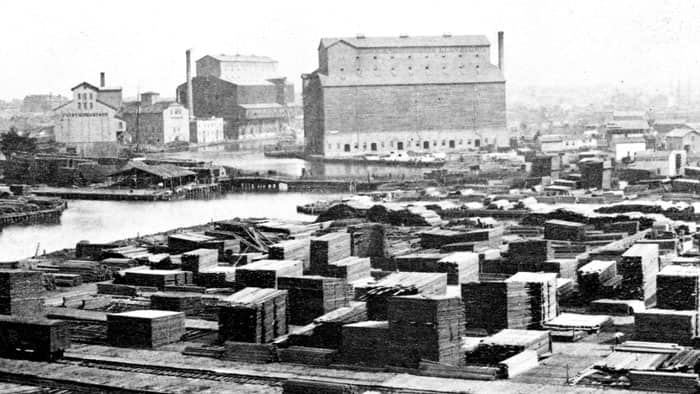

Chicago’s Irish immigrants, many of whom were working class or poor, were particularly maligned by the press and by the wealthy. By 1860, Chicago was the fourth largest Irish city in the United States, according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago. They worked in the stockyards, lumber yards, railroads, and steel mills.

Many of the city’s poor lived in densely packed wooden cottages, with the poorest settling on bleak Maxwell Street. Vice districts, with their boisterous saloons, gambling houses, and prostitution, popped up in various places around the city, including just south of the central business district and at “The Sands,” a lakefront vice district.

Meanwhile, on the other end of the economic spectrum was the so-called “Prairie Aristocracy” – East Coast Protestants who moved to Chicago to amass their wealth. In addition to Bross and Ogden, names such as Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard, Cyrus McCormick, and Potter Palmer and his wife – the philanthropist, socialite, and cultural connoisseur Bertha Palmer – all dominated the political, business, and cultural life of the city. They lived in opulent mansions full of art and fine furniture on South Michigan Avenue, State Street, and Terrace Row.

But rich and poor alike would be displaced come October 1871.

The Spark and the Kindling

Bross’s own Chicago Tribune made this eerie warning mere hours before the fire began. The city had gone months without significant rainfall. It was unseasonably warm on Sunday, October 8 – close to 80 degrees, according to The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow by Richard Bales. The wood that made up most of the city’s structures was completely dry.

As Miller points out, even the roof of the beloved Water Works building – a source of civic pride for Chicagoans – was made of wood. Leaves had begun to fall from the trees, adding to the kindling. Only an inch of rain had fallen since July 4.

The day before the fire, the 185-man fire department battled another terrible fire for 17 hours. That fire, which wiped out four blocks south of downtown, depleted the firefighters, many of whom were injured and had to take time to recover.

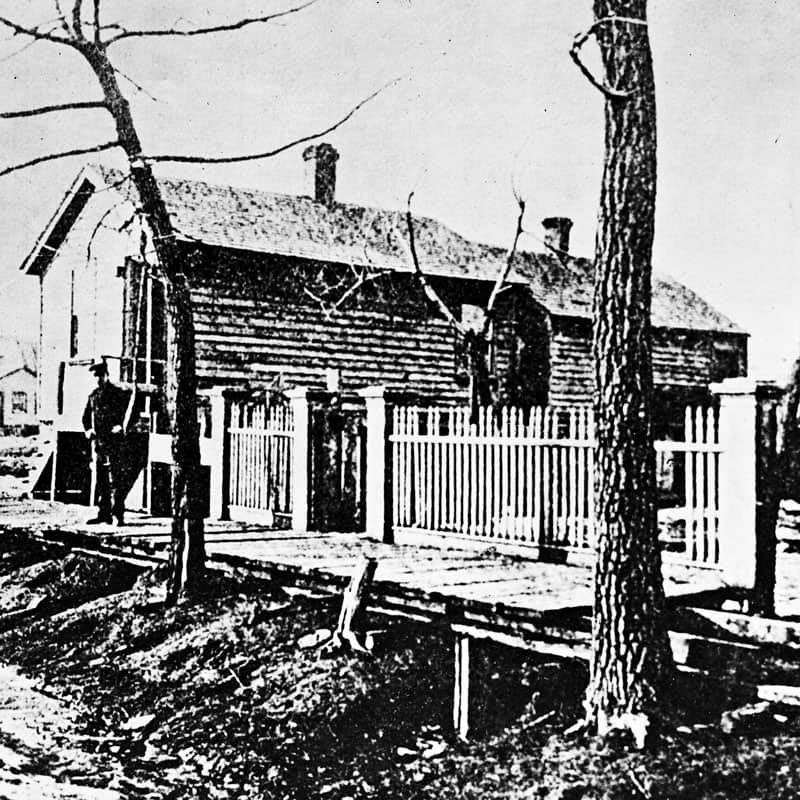

Just southwest of the central business district on DeKoven Street, Catherine O’Leary was getting ready for bed. O’Leary was an Irish immigrant from Kerry, Ireland and ran a successful dairy operation from her modest cottage and barn. She had six cows, a horse, and a wagon. Her husband, Patrick, was a Civil War veteran. They had five children, two of whom attended Catholic school at Holy Family, a nearby parish.

According to O’Leary’s testimony, recounted in Bales’s book, Catherine went to bed sometime around 8 p.m. The O’Learys’ tenants and neighbors, the McLaughlins, were having a party to celebrate a relative’s visit from Ireland. After drifting off to sleep, Catherine’s husband woke her to alert her that a fire had started in the barn.

The Fire

Not long after Patrick O’Leary woke up Catherine, the fire quickly grew out of control, as a strong, hot wind dispersed the flames throughout the densely packed immigrant community.

In the nineteenth century, fear of fire was acute in large cities. Cities established watchmen and fire alarm systems that would, in theory, alert the fire department. But these protections, when combined with human error, weren’t foolproof.

A watchman named Mattias Schaffer spotted the fire on DeKoven Street, but he incorrectly identified the location. When he tried to fix his errors, the operator at the fire alarm telegram department wouldn’t allow him to fix it, saying the firefighters would pass right by the real location, anyway. A nearby shopkeeper who was in charge of an alarm system also sent an alert, but it didn’t work. So the fire department went to the wrong location.

Some passersby gathered to watch the fire as a kind of entertainment, unaware of the danger it posed. People in other parts of the city saw the flames from a distance, but they weren’t worried.

Mrs. Alfred Hebard, a cousin of wealthy Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard, was staying at the Palmer House.

“We immediately took the elevator to the upper story of the Palmer, saw the fire, but, deciding that it would not cross the river, descended to our rooms in the second story to prepare for sleep,” she wrote. Hebard’s account was compiled along with several others in The Great Chicago Fire, by David Lowe.

The fire spread north and then east. The spectators grew increasingly wary, but assumed that the river would stop the flames. But the lumber yards, grain, and wooden bridges that lined the river offered more fuel to the fire, as did the waste and oil atop the water’s surface, thus enabling the fire to cross the river itself. By midnight, a few hours after the blaze began in Mrs. O’Leary’s barn, the fire had reached the present-day Loop.

Mayor Roswell B. Mason was awakened and told the city was burning. The mayor left his home south of downtown and rode his horse toward the courthouse. He sent a desperate telegraph to Milwaukee and Detroit.

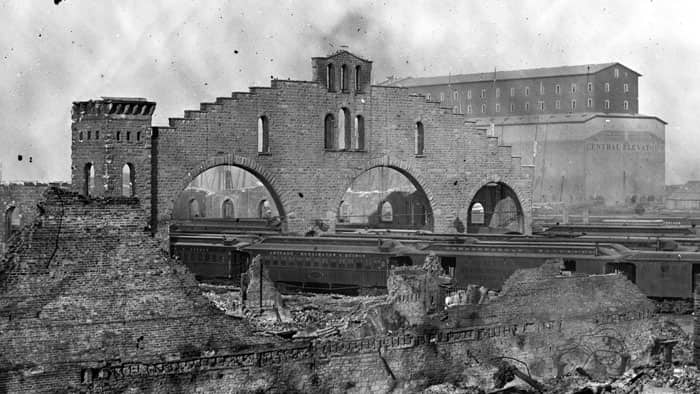

By 1:30 a.m., the fire was raging through downtown. The courthouse, which was supposedly fireproof, caught fire. In a short note, Mason ordered the release of the prisoners as smoke filled the cells in the building’s basement: “Release all prisoners from jail at once, keeping them in custody if possible” – though some prisoners escaped amid the escalating panic. The bell from the courthouse collapsed into the building as the fire overtook churches, theaters, residences, hotels, and banks.

According to Miller’s research, the flames could be seen from 40 miles away. Some witnesses describe seeing what were called “fire devils.”

The intense heat from the fire created its own wind, with gusts so strong it nearly knocked one witness– off his feet. Alexander Frear, a member of New York State Assembly, visiting from New York, described the scene:

The “fire tornadoes” – or “fire devils” – were in fact columns of extremely hot, rising air that rotated as the cooler air descended.

Joseph Edgar Chamberlain, a young reporter from the Chicago Evening Post, noted in his account of the fire the “terrific” noise of the fire as it roared through the streets, “magnified here to so grand an extent, was added the crash of falling buildings and the constant explosions of stores of oil and other like material…The noise of the crowd was nothing compared with this chaos of sound. All these things – the great, dazzling, mounting light, the crash and roar of the conflagration, and the desperate flight of the crowd – combined to make a scene of which no intelligent idea can be conveyed in words.”

By 2 a.m. on October 9, the city had been ablaze for hours. But the flames weren’t finished. Tribune co-owner William Bross had guests in his house when one of them awakened him to warn about the approaching flames. Bross rushed downtown to the newspaper office.

Bross describes a scene in which “all the adjectives in the language would fail to convey the intensity of its wonders.”

When Bross arrived at the office, his co-owner Joseph Medill and the paper’s reporters were already at work. When the building caught fire, Bross knew the Tribune offices would be reduced to ash.

In his account, republished in Lowe’s compilation of witness reports, Bross observed the chaos as the fire lit up the Palmer House and theaters downtown. Almost everyone was carrying something, he said, regardless of its value.

“One woman carrying an empty bird cage; another, an old workbox; another, some dirty, empty baskets. Old, useless bedding, anything that could be hurriedly snatched up, seemed to have been carried away without judgment or forethought.”

While many fled, a man named Joseph Hudlin headed straight for the flames. A Black man who was formerly enslaved in Virginia and moved to Chicago in 1854, Hudlin was head custodian at the Board of Trade. When he heard that the Board of Trade had caught fire, he ran into the burning building to get important documents out of the vault. Hudlin and his wife, Anna Elizabeth, would become heroes of the fire.

Another city landmark went up in flames around 2:30 a.m. The Water Works had been built just two years prior in order to pump clean water into the city from Lake Michigan – an engineering feat at the time. While the structure would survive, the roof caught fire and collapsed, damaging the pumps and engines. The flow of water to the city’s fire hydrants came to a halt.

Many people like Mrs. Hebard, who had fled the Palmer House, went to other parts of the city in search of refuge. But not long after arriving at her cousin’s mansion, it became clear to Mrs. Hebard that they still weren’t safe. Men began covering the roof with carpets that had been soaked in water.

By the morning of October 9, Chicago was unrecognizable. Some on the North Side were beginning to flee to the lake, standing in the water to protect themselves from the flames. Some, as emeritus professor of history at Columbia College Chicago Dominic Pacyga told WTTW, jumped into open graves in the cemetery in Lincoln Park in search of protection, but ultimately suffocated from the smoke.

On the night of Monday, October 9, rain began to fall, helping to extinguish the flames.

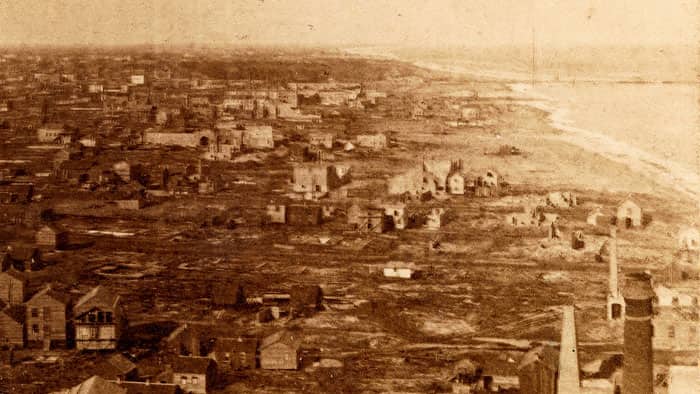

The Aftermath and the Rebuilding

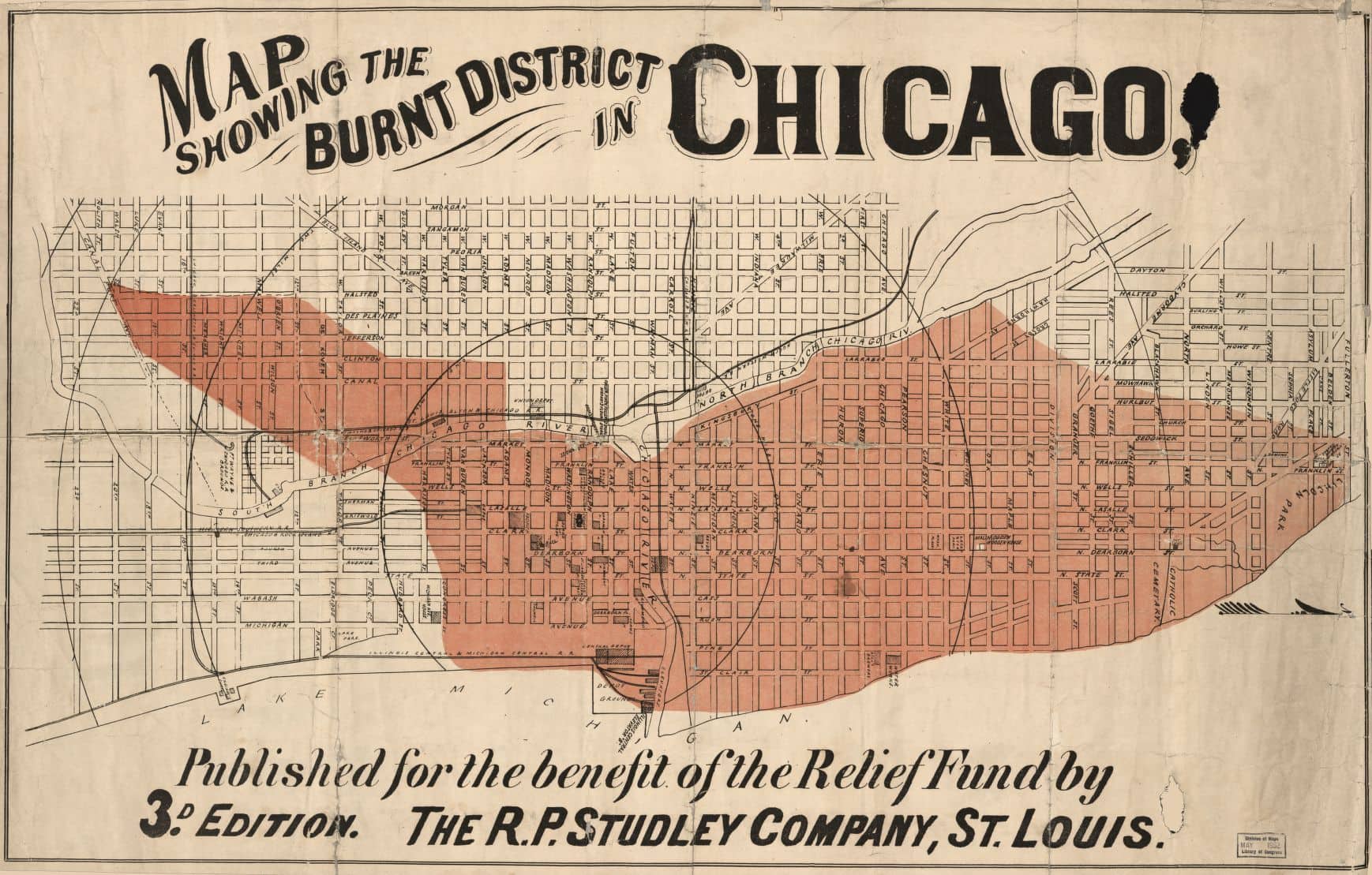

By the time it was over, the fire burned a stretch of the city that was nearly a mile wide and four miles long. According to the Chicago History Museum, 18,000 buildings were destroyed and damage was estimated at $200 million. The Crosby Opera House, the Palmer House hotel, the courthouse, and the Board of Trade were all lost. The damage on the North Side was particularly bad.

Though many people believe the Water Tower was the only structure in the burn zone to survive, a handful of others also made it. Holy Family Church, where the O’Learys worshipped, avoided the burn zone. Lore said that the church’s priest, Father Arnold Damen, prayed when he heard the news about the fire and that the winds miraculously shifted to spare the church.

Though not in the burn zone, the stockyards and most of the railroads – key to the city’s economic success – also survived.

And then there was the human toll. Some 120 bodies were recovered, but an estimated 300 died in the blaze. The destruction left 100,000 people homeless. Joseph Hudlin’s wife, Anna Elizabeth, took in 5 other families – Black and white – in their cottage. The Tribune called her an “angel of the fire.”

On Tuesday, October 10, with the fire completely out, Mayor Roswell B. Mason issued a series of executive orders to prevent the city from falling into further chaos. His orders established the price of bread, banned smoking, and forbade wagon drivers from increasing their pricing. Mason also enacted martial law and brought in troops in an effort to keep the peace. The city remained peaceful as the rebuilding efforts began that same week while, as is often said, the ground was still hot.

While some eyewitness accounts reported looting during the fire, some newspaper reports set out to sensationalize an event that did not need further fabricated drama. According to Miller, some reporters made up stories of looting and drunken criminals. Some reporters expressed anti-immigrant and racist sentiments.

“One reporter described ‘dirty,’ ‘villainous’ Negroes moving through the streets ‘like vultures in search of prey’ and ‘hollow-eyed’ Irish women in bedroom slippers and torn dresses moving ‘here and there, stealing,’” Miller wrote.

Gallery: The Aftermath

No one bore the brunt of the anti-immigrant sentiment more than Catherine O’Leary and her family. The myth that persisted for decades was that Mrs. O’Leary had been milking her cow in her barn in the evening when the cow kicked over a lantern. But Chicago’s police and fire departments conducted an investigation not long after the fire and found no evidence that anyone was in the barn that night.

As historian Sarah Marcus told WTTW, another theory suggests that one of the O’Learys’ tenants snuck into the barn to get milk and knocked a lantern over. Others say neighborhood kids playing poker knocked over a lantern, or that a neighborhood man was smoking a pipe.

Still, the reporters harassed Mrs. O’Leary, knocking on her door on the anniversary of the fire each year. Though her cottage survived the fire, most of her cows perished and her business was destroyed. The family eventually moved to avoid harassment from the press. She wouldn’t be formally vindicated until 1997. The cottage was torn down, and today, the Chicago Fire Academy stands in its place.

Like the O’Leary family, other immigrants and poor Chicagoans moved further away from the city center as Chicago was rebuilt, in part because new fire codes required more expensive building materials, which led to higher priced housing.

Not long after the fire, William Bross traveled to New York. As he talked to the press there, he used the fire as a selling point – a chance to move to a city on the verge of being rebuilt into something great.

The city recovered and grew. A few years after the initial rebuilding efforts, Chicago got another facelift – one that reached new heights. Chicago claims to be the city that invented the skyscraper. Some architecture experts say that the 10-story Home Insurance Building at LaSalle and Adams streets was the world’s first skyscraper, built in 1885. (It was torn down in 1931). Just over two decades after the fire, Chicago was home to the 1893 World’s Fair, where its displays of art, architecture, and the first Ferris wheel showed that not only had the city recovered, but it had become a center of innovation.