How World War I Transformed Chicago

Daniel Hautzinger

April 10, 2017

“It might seem surprising today, but a hundred years ago U.S. public officials wanted more Mexicans to enter the United States,” Joseph Gustaitis writes in his book Chicago Transformed: World War I and the Windy City. Not that  Joseph Gustaitis, author of 'Chicago Transformed.' Image courtesy Joseph Gustaitisthe reason was benevolent. In 1917, two months before the U.S. officially entered World War I, Congress passed a law limiting immigration to literate foreigners, increased the immigrant tax required to enter the country, and outright banned migrants from many parts of Asia. Along with the ongoing war in Europe, this drastically reduced the number of immigrants to the U.S, especially from Europe. But as millions of Americans left to join the war, industries needed to find new sources of labor to work on railroads, farms, and in factories.

Joseph Gustaitis, author of 'Chicago Transformed.' Image courtesy Joseph Gustaitisthe reason was benevolent. In 1917, two months before the U.S. officially entered World War I, Congress passed a law limiting immigration to literate foreigners, increased the immigrant tax required to enter the country, and outright banned migrants from many parts of Asia. Along with the ongoing war in Europe, this drastically reduced the number of immigrants to the U.S, especially from Europe. But as millions of Americans left to join the war, industries needed to find new sources of labor to work on railroads, farms, and in factories.

Hence the waiving of the literacy provision for Mexican workers, which led to a continually growing influx of Mexicans into America, including to Chicago. From 1910 to 1920, the Mexican population in Chicago skyrocketed from 102 to 1,224, according to the U.S. Census, and those figures are probably low. Thus began a large-scale Mexican migration to Chicago that is evident in the many Mexican neighborhoods of the city today.

But that was nothing compared to the explosion of Chicago’s African American population during the war years. From 1916 to 1918, the black population doubled, from 58,056 to 109,594. The Great Migration had begun.

“The main point I try to make about Chicago during World War I is that the changes that occurred were first demographic,” Gustaitis said in a phone conversation. “Four million men went into the military, which made for a serious labor shortage, especially in Chicago, where you had a need for a lot of unskilled labor in places like steel mills and meatpacking houses.”

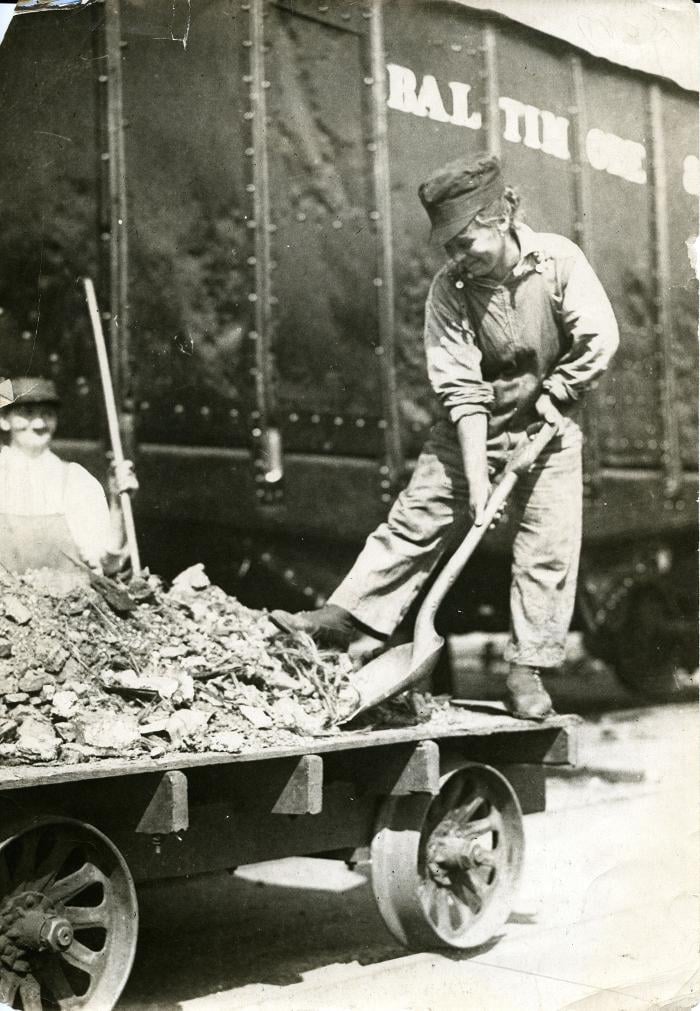

Between enlistment and immigration restrictions, new jobs opened up to women, African Americans, and Mexicans during the war. Image courtesy Joseph GustaitisSouthern African Americans were drawn north in part by editorials and want ads in the Chicago Defender, the largest black newspaper in the country, which was distributed throughout the South by black Pullman Porters. Once in Chicago, black migrants found work in the stockyards, on railroads, in lumberyards, and other industries, and began settling primarily on the South Side in the neighborhood now known as Bronzeville. With the Great Migration came the growth of a bustling jazz scene in the city – including such legendary musicians as King Oliver, Sidney Bechet, and Louis Armstrong – as well as the emergence of the distinctive Chicago blues.

Between enlistment and immigration restrictions, new jobs opened up to women, African Americans, and Mexicans during the war. Image courtesy Joseph GustaitisSouthern African Americans were drawn north in part by editorials and want ads in the Chicago Defender, the largest black newspaper in the country, which was distributed throughout the South by black Pullman Porters. Once in Chicago, black migrants found work in the stockyards, on railroads, in lumberyards, and other industries, and began settling primarily on the South Side in the neighborhood now known as Bronzeville. With the Great Migration came the growth of a bustling jazz scene in the city – including such legendary musicians as King Oliver, Sidney Bechet, and Louis Armstrong – as well as the emergence of the distinctive Chicago blues.

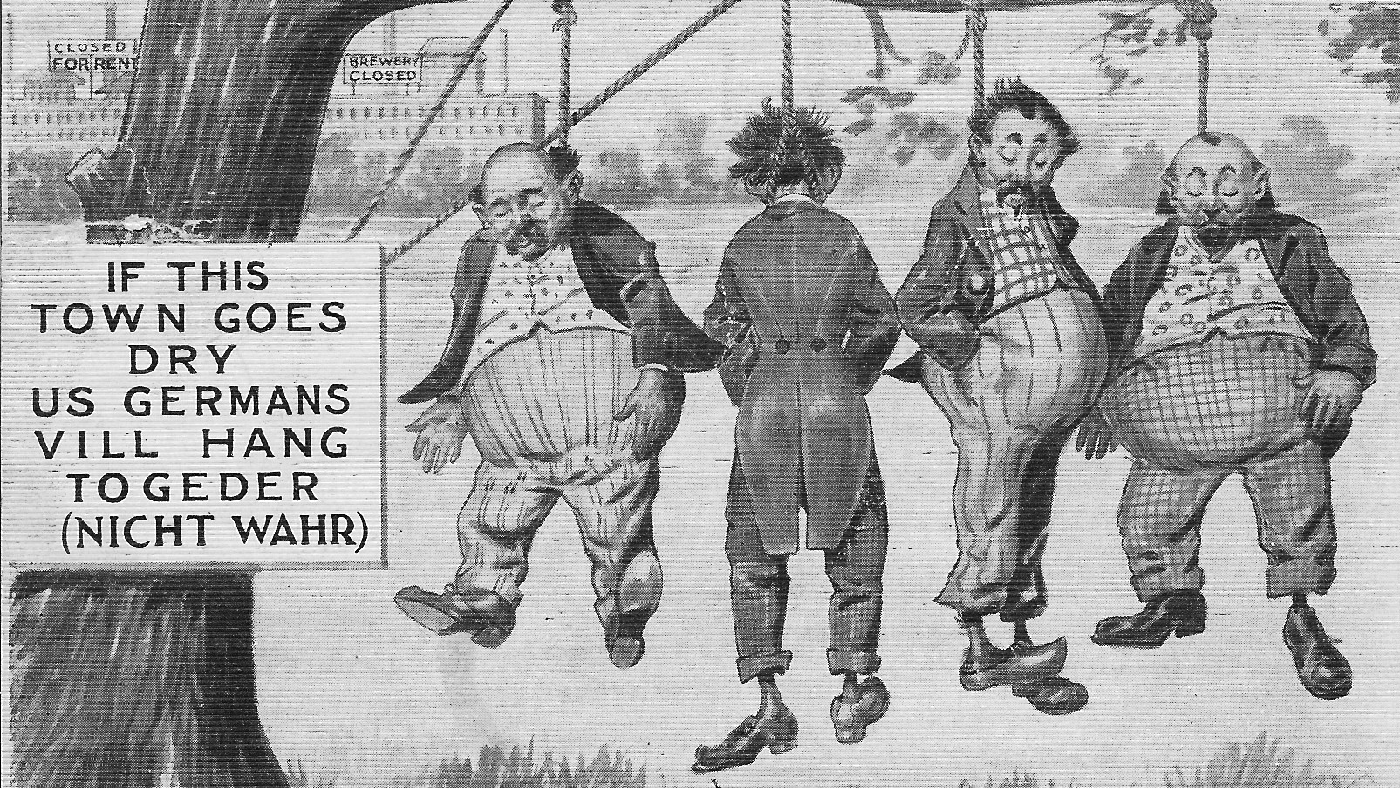

Along with the migration of African Americans and Mexicans to Chicago, another demographic change occurred during World War I, but in a downward direction. As America went to war against Germany, anti-German sentiment flared up back home. “Chicago was a very German city, with more than twice as many Germans as the next largest group, which was the Irish,” Gustaitis said.

Yet between 1910 and 1920, the number of Germans in Chicago decreased by nearly 80,000 people, according to the Census. “It wasn’t that these Germans got up and left, they just didn’t identify themselves as German anymore, and they changed their names from Schmidt to Smith, for example,” Gustaitis explained.

Anti-German sentiment also contributed to the arrival of Prohibition, which was officially signed into law two months after the end of the war with the Eighteenth Amendment. “All the great brewers in the Midwest, like Schlitz, Pabst, Blatz, Anheuser, and Busch, were born in Germany and spoke German,” Gustaitis said. “So the Prohibition forces were able to paint beer as anti-American.”

Efforts to conserve food during the war also led to restrictions on alcohol: the use of food products in distilling liquor was banned by Congress in 1917, while in 1918 an act prohibited the manufacture of wine and beer. “This might have been what persuaded enough people to actually pass the Eighteenth Amendment,” Gustaitis said.

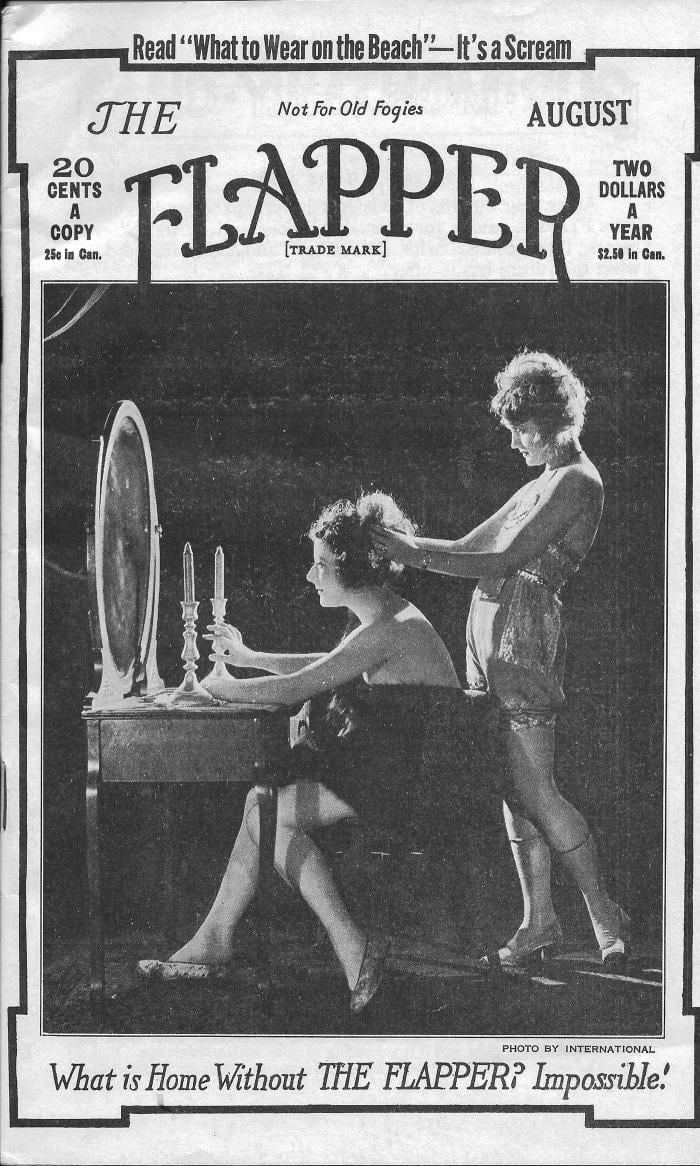

'Flapper' magazine was based in Chicago and was a sign of the first sexual revolution. Image courtesy Joseph GustaitisWith Prohibition came that icon of the Roaring Twenties, the flapper – or so most people think. In fact, the word “flapper” was already in use in America as early as 1913, when a Chicago Tribune article mentioned it in a discussion of English slang. With the labor shortage during the war, many single women began moving to cities to take over jobs previously closed to them, and enjoyed a flapper lifestyle in boardinghouse neighborhoods and entertainment districts. Chicago itself was home to Flapper magazine, and the city’s newfangled jazz provided the soundtrack for what has been called the first sexual revolution, which began during the war years and continued into the Twenties.

'Flapper' magazine was based in Chicago and was a sign of the first sexual revolution. Image courtesy Joseph GustaitisWith Prohibition came that icon of the Roaring Twenties, the flapper – or so most people think. In fact, the word “flapper” was already in use in America as early as 1913, when a Chicago Tribune article mentioned it in a discussion of English slang. With the labor shortage during the war, many single women began moving to cities to take over jobs previously closed to them, and enjoyed a flapper lifestyle in boardinghouse neighborhoods and entertainment districts. Chicago itself was home to Flapper magazine, and the city’s newfangled jazz provided the soundtrack for what has been called the first sexual revolution, which began during the war years and continued into the Twenties.

A corollary to that revolution was the movement of women into the labor force during the war, with some 12 million gainfully employed at the end of 1918. While many of them either lost or left their jobs once the war ended and the soldiers returned home, the prospect of jobs brought rural women to the city, enabled an independent lifestyle, and helped contribute to a growing American feminist movement that would bear fruit in 1920 with the passage of women’s suffrage.

Nor were women the only ones who made strides during the war years. Chicago itself experienced an economic boom from exporting steel and food to European countries, leading to a prosperous following decade. By the 1920s, due in part to World War I, Chicago was a bustling metropolis flooded with new music genres and ethnic groups as well as thriving industries. The city had solidified itself as the booming capital of America’s “inland empire.”