'Home from School' Tells One Story of Indian Boarding Schools in Order to Heal

Daniel Hautzinger

November 19, 2021

Independent Lens – Home from School: The Children of Carlisle will be available to stream.

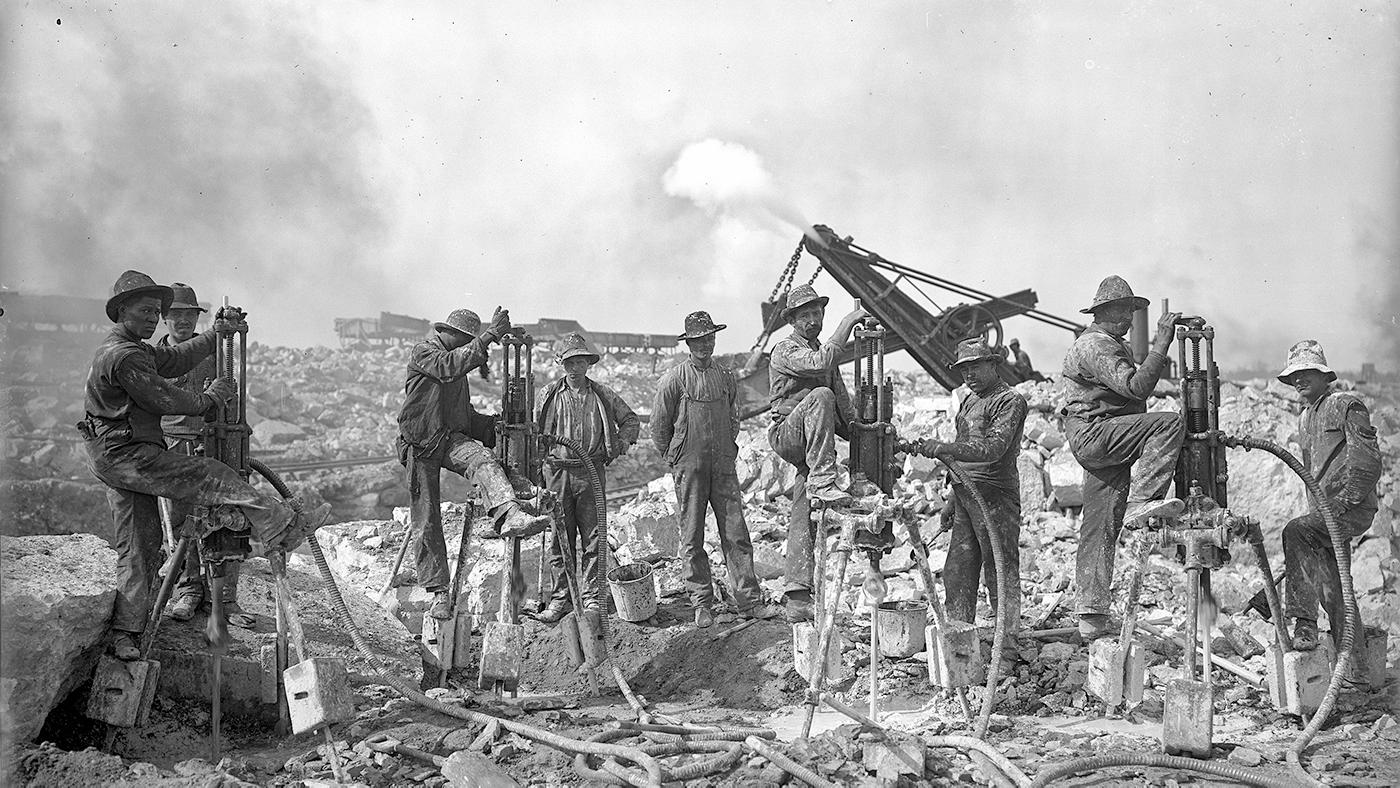

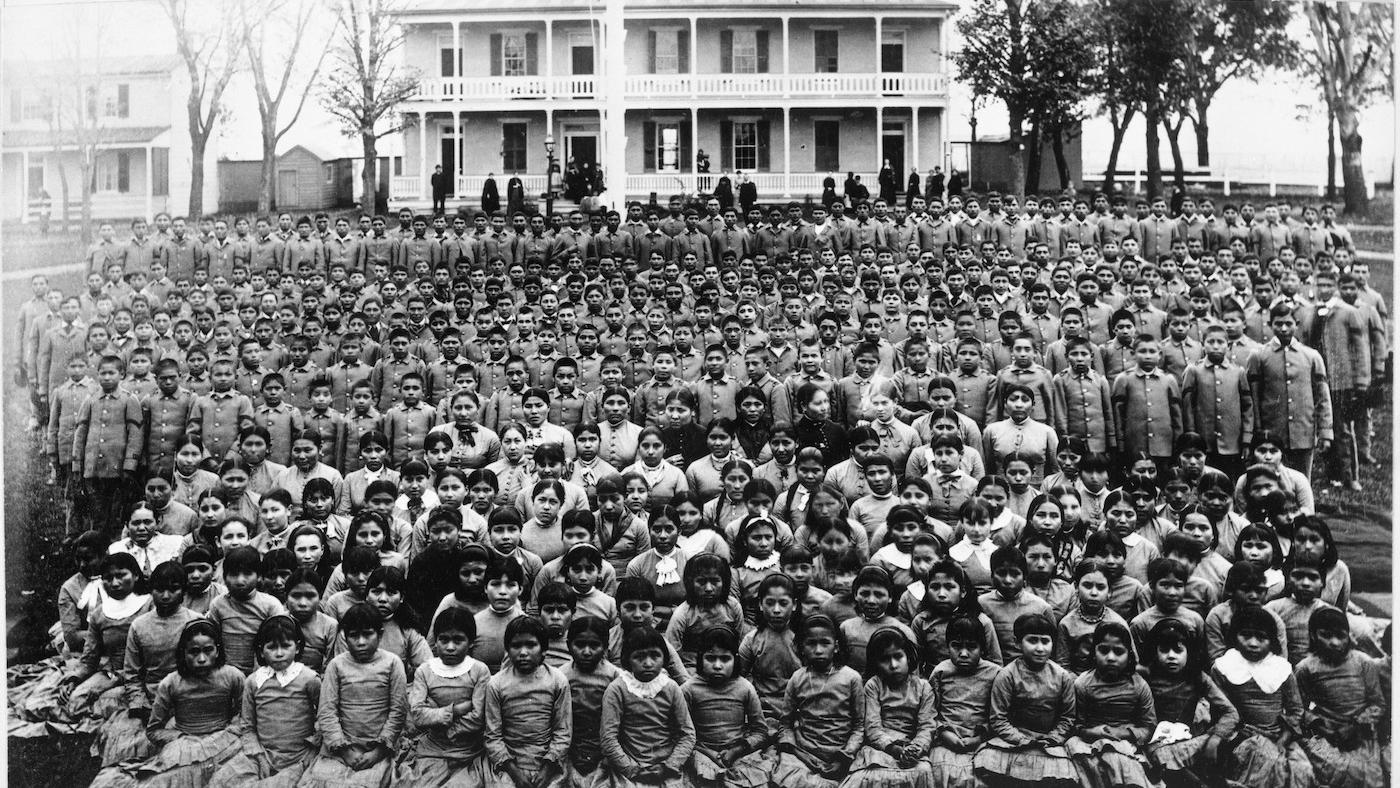

Three children are sent away from their homes in Wyoming to a boarding school in Pennsylvania. There, they were put into uniforms, their long hair was shorn, their names—Little Chief, Horse, and Little Plume—were replaced, and they were forced to learn English and forget their native language, in an attempt at forced assimilation. All three died within a year of each other there—three of a total 238 Native Americans who died, mainly of disease, at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in its several decades of existence.

Chief Sharp Nose of the Northern Arapaho learned of his son’s fate while guiding President Chester Arthur to Yellowstone, and the president informed him that Little Chief had died, half a world away.

More than a century later, the Northern Arapaho of Wyoming’s Wind River Reservation brought Little Chief, Horse, and Little Plume back to the home they had left forever, repatriating their remains from Carlisle. The story of that journey is told in the new Independent Lens documentary Home From School: The Children of Carlisle.

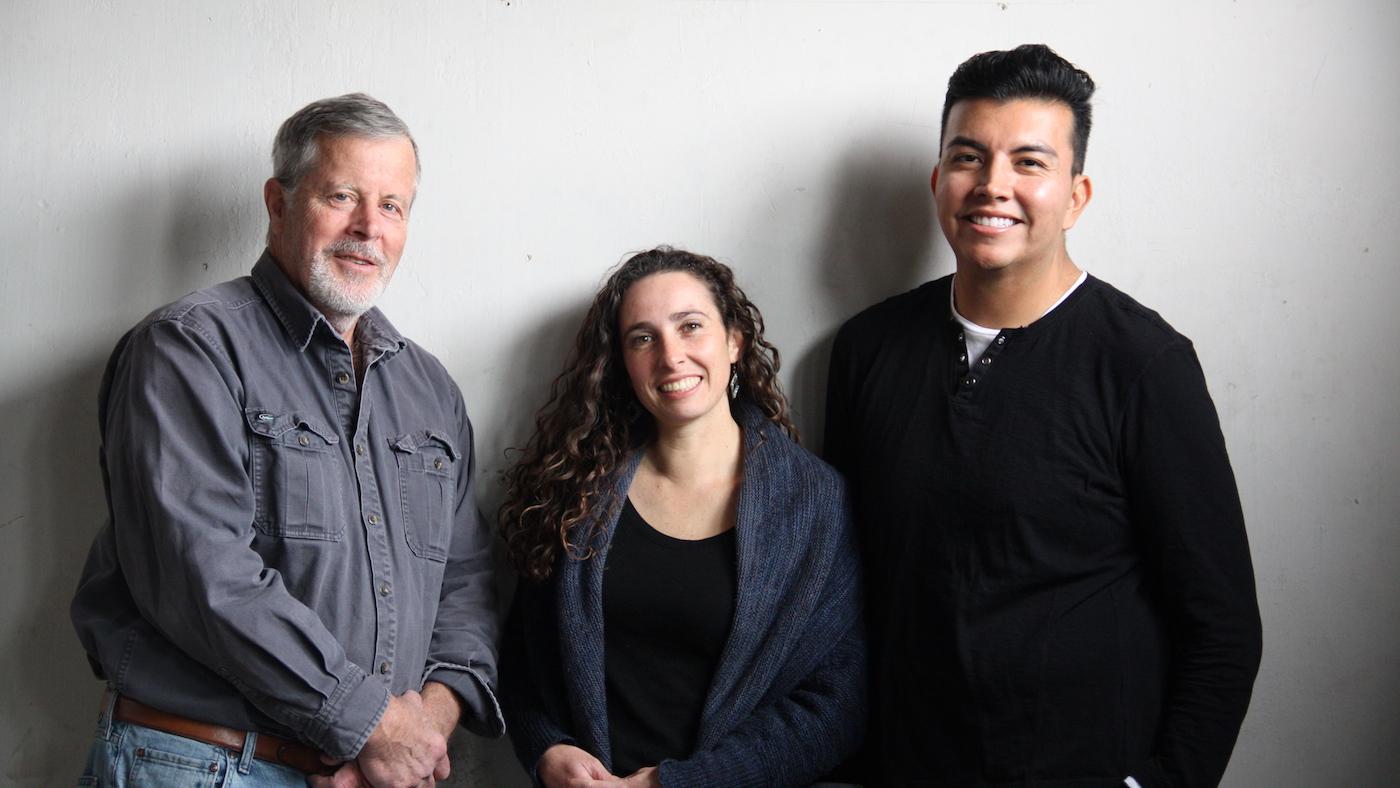

“One of my favorite things about this film is that it is the Arapaho story and it is the tribe reclaiming their history. It’s the tribe reclaiming the narrative, and it’s them taking ownership of that and telling it how they want to tell it,” says Sophie Barksdale, a co-producer of the film. “You’re hearing the story from the people who are in it, and you’re hearing the context. And you’re seeing the pain, but then you’re also seeing the hope and the healing—and that’s the piece that I really love, that thread of hope throughout the film. It is that pride of identity and that ‘we’re going to do it for ourselves’ piece.”

“Native people, we’re in this cycle of generational trauma from everything that we’ve been through, and that’s really a key part of why we are the way we are,” says Jordan Dresser, an associate producer of Home from School and a member of the Northern Arapaho Tribe who also serves as chairman of the Northern Arapaho Business Council. “This film talks about closing those cycles so that we can step into who we’re meant to be, which is basically anything.”

Yufna Soldier Wolf led the repatriation effort. Photo: Caldera Productions

Yufna Soldier Wolf led the repatriation effort. Photo: Caldera Productions

That idea of finding closure in order to look to the future is articulated in the documentary by Yufna Soldier Wolf, who leads the repatriation effort. “Yufna’s pitch, if you will, was: ‘We need to deal with this. We need to do it so that we can move on to a real future where a kid can dream of being a doctor or a lawyer or an engineer and not be burdened with some vague memory of a great-grandpa who never came back from some far-away school,’ ” says Geoffrey O’Gara, the director, writer, and producer of Home from School.

“I remember having a conversation with Loveeda White [a young member of the Northern Arapaho who appears in Home from School] and saying to her, ‘Gosh, it’s really hard when you get all this pressure from your parents and your relatives: what are you going to be? What are you going to do when you get to university?’” recalls Barksdale. “And she said, ‘We don’t get that. No one expects us to go to university. We’re lucky if we finish high school. No one has any expectations.’ That really gave me pause and made me realize that the narrative we tell ourselves, the narratives that we tell children, really matter.”

“I think that it’s changing and it’s exciting,” says Dresser. “At a screening we had, the students were a wide range: people were in American Indian Studies, one was in pharmacy school, one was in law school. It made me think: this is what it was meant for. For us to open up these doors, for us to step into our power.”

O’Gara says, “You hear Yufna and others say it: ‘We’re tired of being viewed as like artifacts, like we’re this sort of romantic thing from the past.’ What is it like to be Native American in the here and now?”

The here and now is a time when the troubled history of Indigenous boarding schools is becoming increasingly publicized. Earlier this year, United States Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland—an enrolled member of the Laguna Pueblo—announced a federal initiative that will “uncover the truth and lasting consequences of these schools,” in the wake of the discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves at Indian residential schools in Canada.

“It was a good time 120 years ago to tell this story,” says O’Gara. “It’s not in the history books.”

“I think Canada has been slightly more progressive than us,” says Dresser. “They at least acknowledged it, because individuals who were able to prove that they suffered abuse in those schools were able to get a monetary settlement.” (Canada, where state-funded schools operated until the 1970s, offered billions of dollars in compensation as part of a settlement in 2008.) “Here in America, it’s just never been discussed.”

Home from School at least makes people aware of that history. “I think it’s meaningful to be able to bring this story to families so that there’s that feeling of compassion: ‘Gosh, what if that was my child being sent across the country?’” says Barksdale, who is currently working on a documentary with Dresser about missing and murdered Indigenous women that also aims to spark such empathy. “There’s this lack of compassion for Native women, because they’re very much seen as, ‘That’s not me, and that’s not anyone I know’—it’s a statistic. With this film that we’re working on, we really want to show who these women are.”

It’s a similar goal to that of Home from School: to tell the individual, human side of a dark tale. “I think this film is meaningful because it’s telling a story that, one, needs to be told—but also, it’s not being told just to tell it,” says Dresser. “It’s telling it with a purpose, which is ultimately about healing. I think it just shows that there are so many possibilities of finding healing and closure despite what you may go through.”