Exploring the Diversity of American Music Through Its Influences—and Food

Daniel Hautzinger

April 7, 2022

Now Hear This airs Fridays at 9:00 pm on WTTW and is available to stream at the same time.

Scott Yoo was discussing the third season of his PBS series Now Hear This when he brought up a restaurant in Columbia, Missouri, where he lives. “Columbia is a relatively small, Midwestern college town, but smack dab in the middle of it there is a very, very credible Burmese restaurant,” he said. “In the middle of Missouri. And I feel like [its presence] is so much more important even than the actual cuisine that they create. When you have that type of cuisine with a completely different flavor profile and completely different ingredients, you understand, ‘Ah, the world is bigger than our little town in Missouri.’”

Why was Yoo extolling the virtues of having diverse restaurants in the middle of an interview about a show exploring the life, work, and influences of composers of classical music?

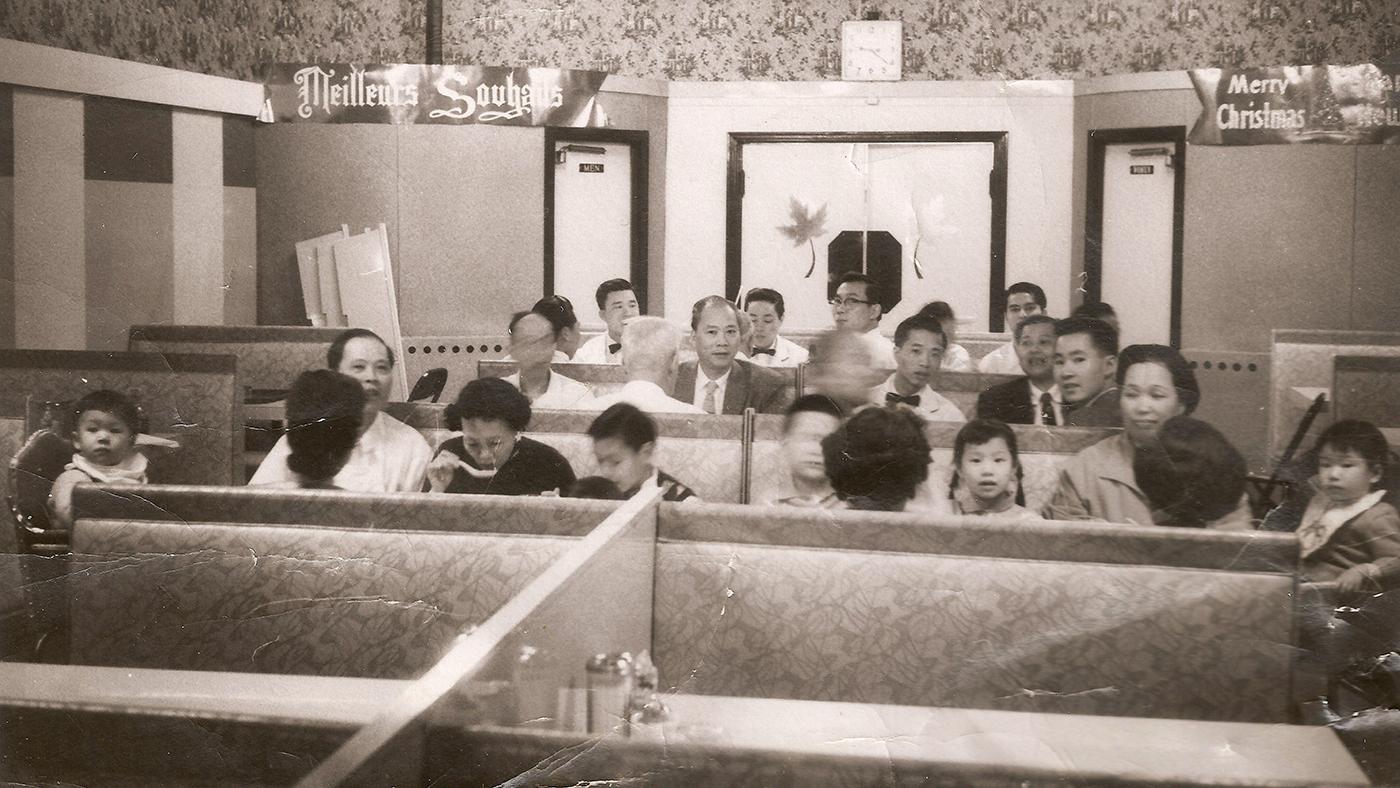

For one thing, Now Hear This frequently incorporates creative endeavors beyond music to help illustrate cultural contexts and connections, including food: in the new season, Yoo eats soul food at Bronzeville’s Pearl’s Place Restaurant in order to understand the Great Migration of Black Southerners such as the composer Florence Price north to cities like Chicago; he also helps the composer Reena Esmail’s parents prepare a South Asian meal at their home in California while learning about Esmail’s background and the Hindustani music she draws upon.

But the existence of a Burmese restaurant in Columbia also exemplifies, in a way, what Yoo is trying to do in Now Hear This. He explained: “It’s not that we’re going to show everyone the complete breadth of the Hindustani music canon”—or blues, or gospel, or samba, or other musical traditions that are elucidated in the new season. “But if we can point a camera at the deepest lake in the world and say, ‘That’s two miles deep, and you’re seeing the first three inches of it,’ then I think we’ve done a service to America.”

This season of Now Hear This explores the idea of American classical music by focusing on several composers: Amy Beach, Price, Aaron Copland, and Esmail and the Chicago-based Brazilian guitarist Sergio Assad.

“In the first two seasons, I would go travel around Europe and I was inhabiting the classical space,” Yoo said. “So even though I was in Europe, I felt very at home and very comfortable. The irony is that, in season three, listening to essentially the Itzhak Perlman of Indian classical music and being taught how to try to play in that style—even though we were shooting that in the United States, I felt much more out of place, and it felt much more foreign to me to shoot season three—even though we were home!”

While Kala Ramnath, the violinist who demonstrates some Hindustani music for Yoo, plays the same instrument as him, “it’s almost like playing a different instrument because she’s holding the instrument in front of her shoulder…and she’s using degrees of freedom that I just don’t understand,” he said with amazement. Watching a talented musician trained in the Western classical tradition try to emulate an Indian classical musician gives a sense of how complex and refined the Hindustani tradition is.

“Classical musicians, we kind of think we’re the best,” Yoo said with a sense of humor. “But we’re wrong. The people that I interacted with and that I got to hear from four feet away were just stunning, stunning virtuosos of their craft.” That includes not just Ramnath but, among others, the blues guitarist John Primer, Sergio Assad and his daughter Clarice Assad, and the gospel musicians Vernon Oliver Price and Dr. Lou Della Evans Reid—both of whom are in their 90s. They all provide a glimpse of the vast and varied influences and styles that go into American music, both popular and classical.

“America is an idea,” Yoo said. “And really anyone can fit in there. I—with Korean and Japanese ancestry—fit in. Somebody who’s Black fits in. Somebody who’s Indian fits in. Somebody from Brazil fits in. The American experience is such an impossibly wide one.”

And yet America hasn’t always accommodated everyone, including people like Florence Price. Born in Arkansas, she was the first woman of color to have a piece performed by a major American orchestra, when the Chicago Symphony Orchestra premiered her first symphony in 1933. She wrote in the classical tradition but incorporated the influence of African American musics and her experience as an organist for silent films—Yoo hears gospel in Chicago at the First Church of Deliverance, Chicago blues and jazz in a converted church, and silent film accompaniment at the Music Box Theatre.

But despite the success of her symphony—one reviewer called it a “faultless work…worthy of a place in the symphonic repertoire”—she remained stymied by what she once called her “two handicaps—those of sex and race.” A number of her manuscripts sat ignored in a dilapidated, abandoned house in a small town south of Chicago and were only discovered more than fifty years after her death.

“For me, Florence Price is the classic underdog story,” Yoo said. “The sad thing is that the arc of her life wasn’t complete in her lifetime. The arc of her life is being completed now, now that her music has become popular.”

In Now Hear This, Yoo says that, “Florence Price gave us the first truly American classical music, based in the Romantic tradition but influenced by the music of Black America.” Like Esmail’s Hindustani-influenced pieces, or Assad’s Brazilian-infused works, it’s as American as a Burmese restaurant in the middle of a small town in Missouri.