Roebling Bridge

Roebling Bridge

John Roebling may be famous for the Brooklyn Bridge, but his first creation came 16 years earlier with this suspension bridge that connected Ohio and Kentucky — a free state and a union state in the midst of the Civil War.

When it was proposed in 1846 that a massive bridge be constructed across the Ohio River, it met widespread opposition from diverse corners.

Cincinnati merchants didn’t want the competition from their Kentucky neighbors, where the cost of living was lower. Steamboat industry leaders didn’t want river traffic impeded and shipments slowed.

And then there was the issue of slavery: the bridge would connect a slave state to a free state.

Slaveholders in Kentucky feared that it would provide enslaved people with an easier escape route. And so, when the State of Kentucky gave the project its stamp of approval, it required the Covington & Cincinnati Bridge Company to reimburse slaveholders for any escapes facilitated by the bridge.

Abolitionists in Cincinnati had their own concerns. The board of the Kentucky company behind the project had several slave owners among its members – all of whom stood to benefit financially from the bridge.

“People in the Ohio General Assembly said…‘We don’t want to implicate Cincinnati in any way,’” said Paul Tenkotte, history professor at Northern Kentucky University and author of several books on the region. “They felt that they should put up as many possible hurdles against the bridge as they could.”

And so they did.

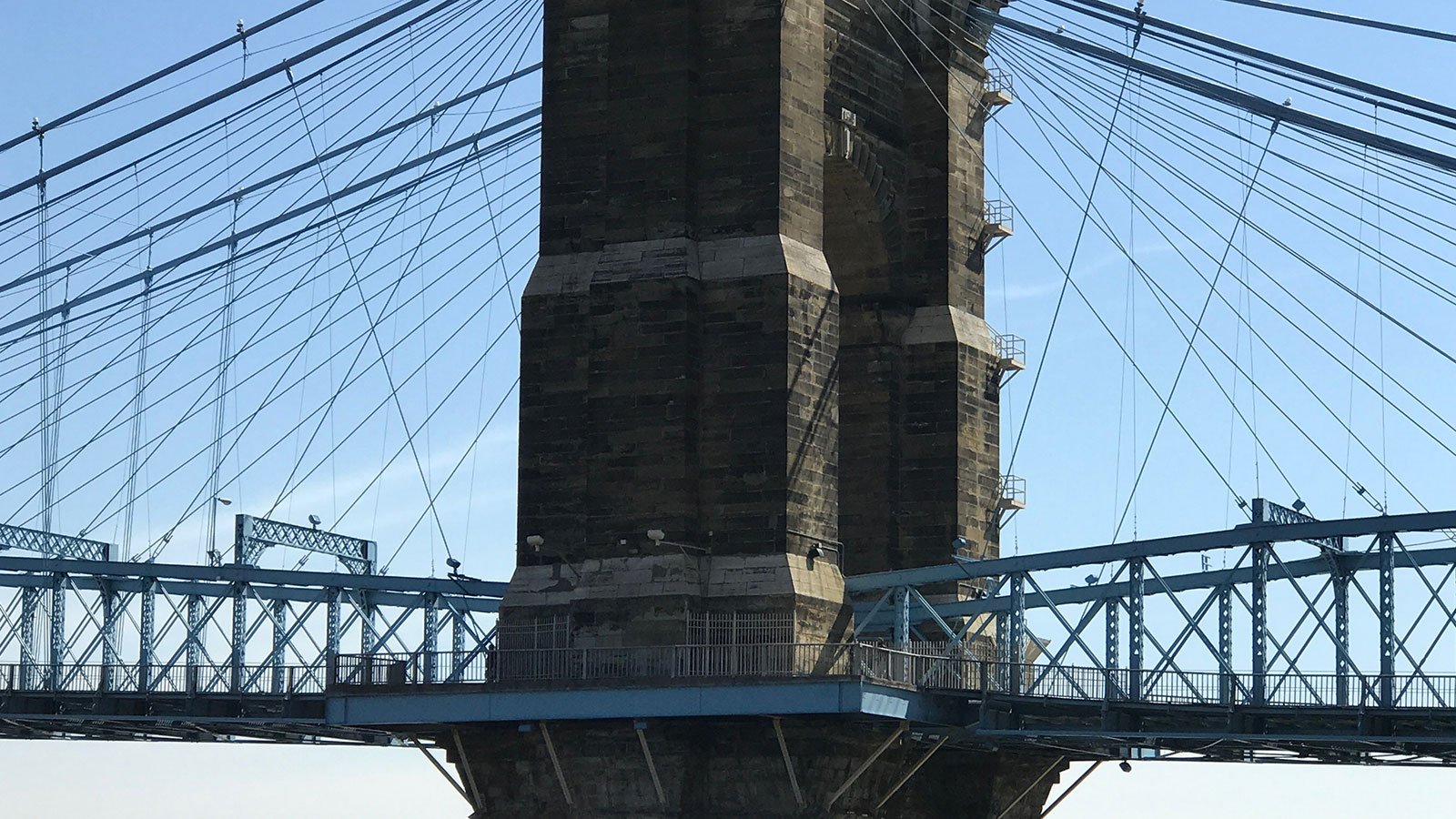

When the Ohio legislature finally approved the project, the bridge’s fate was still an open question. The stipulations called for a longer bridge than the world had ever seen – high and wide enough for steamboats to pass underneath, or at least 122 feet above the water with a span of at least 1,000 feet.

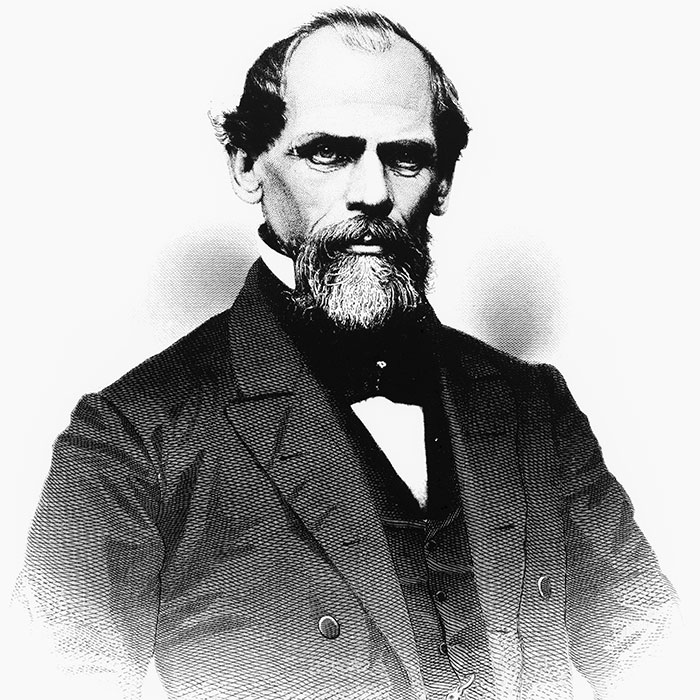

To design this ambitious project, the Covington and Cincinnati Bridge Company hired Prussian-born engineer John Roebling.

“They figure he is the one man who can meet all of the stipulations,” said Tenkotte.

Roebling had made a name for himself as an ambitious and meticulous pioneer in bridge technology, revolutionizing bridge building with his wire cable-spinning technologies and iron rope.

Legend has it that Roebling was inspired by a previous catastrophe on one of his job sites after hemp rope ripped, causing a fatal accident. “He said to himself, ‘I am going to design and patent a kind of iron rope that will have such a high tensile strength that these kinds of accidents won’t ever happen again,’” said Tenkotte.

To do that, Roebling developed a method for stranding and weaving wire rope and spinning wire cables on site. These technologies allowed Roebling to design and support bridges with longer spans than ever before – including the Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge, which Roebling himself designed. That bridge stretches across the Niagara River and has a span of 821 feet.

That was still smaller than the bridge required by Ohio leaders.

But Roebling had a plan. He would build two massive towers on opposite banks and string his iron cables across. He would then suspend the deck of the bridge from the cables and strengthen it with a system of diagonal stays and iron trusses.

Work on the bridge began in 1856. But after the Panic of 1857, funds dried up and work ground to a halt. The start of the Civil War four years later worsened matters and made a project that connected Ohio and Kentucky seem insurmountable.

But in 1862, Confederate forces began advancing north toward Cincinnati, and the Union army needed to send troops across the Ohio River. In an effort to defend the city, a temporary pontoon bridge was hastily constructed. Thousands of troops rushed across the bridge into Kentucky to build fortifications. The mission was a success and Confederate troops retreated.

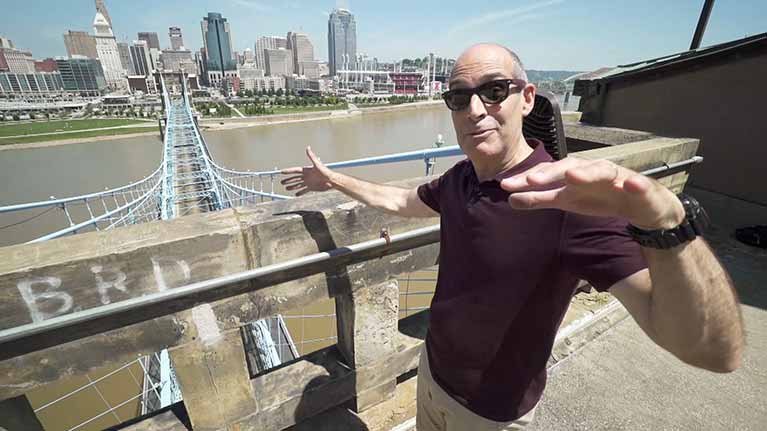

Geoffrey takes viewers to the top of the Roebling Bridge to learn about the engineering feats that made it possible.

The incident transformed the bridge project into a matter of national defense. Money poured in, and construction resumed – this time with ample funding and minimal, if any, opposition.

The Civil War came to an end in the summer of 1865, and Roebling’s bridge was completed the following year.

By that time, Roebling had already moved onto his next project: the Brooklyn Bridge, an even larger suspension bridge spanning the East River. Sadly, an accident at that project led to an infection that took Roebling’s life.

But his legacy lives on in his many discoveries and accomplishments. Roebling proved that a suspension bridge could span remarkable distances, laying the foundation for the design of many more around the world and across the country, from the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge to the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in New York.

Many of them, in addition to being engineering achievements, are stunning works of art that enhance the local landscapes.

“Roebling had this sense that he wanted things to be beautiful. He adored beauty. He adored freedom,” said Tencotte. “But he also was a man of his time and a man of his age who certainly wanted to see civil engineering help people.”

Long after his lifetime, Roebling’s wire cables continued to make possible other great feats of engineering, including the elevator and, with it, the skyscraper.

“He had a mammoth influence on the nineteenth century and industrialization as we know it,” said Tencotte.