History of Pilsen

Pilsen’s story is one of struggle and triumph: recently arrived immigrants struggling to navigate a foreign, often unwelcoming new land; factory workers struggling for a livable wage and an eight-hour day, even in the face of violent suppression; neighbors struggling to make their streets safe, their schools respectable, their air clean enough to breathe, and their homes secure.

It is only in recent years that many of those struggles have borne fruit and given way to a new struggle: one to maintain the identity and affordability of what is now a profitable location for developers and investors.

The first immigrants to make a home on Pilsen’s long-standing prairie grass were from Ireland. Although they would eventually become the most powerful political constituency in Chicago, in the early days they were treated as less than dirt. They arrived by the hundreds in the 1840s, promised ample work for anyone with a strong back and willing hands.

First, they built the Illinois and Michigan Canal, connecting the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River. Then they built the Southwestern Plank Road, which became today’s Ogden Avenue. Soon after, they built the Burlington Railroad tracks.

Their backbreaking labor fueled historic growth. When these immigrants arrived, Chicago was on the cusp of becoming a great metropolis. As the canal, road, and rail lines became operational between 1840 and 1855, Chicago’s population grew exponentially – from 4,470 to more than 75,000 in just 15 years.

The infrastructure wasn’t just good for Chicago business owners; it was good for the region. Corn, wheat, pork, and cattle traveled via train, ship, or horse-drawn cart from far-flung Illinois farms. Small towns emerged from the dirt along the canal to the west. Lumber traveled across Lake Michigan from the Northwoods, boosting the economies of Wisconsin and Michigan. Factories, stockyards, breweries, and lumberyards sprang into existence in what would become Pilsen, where workers transformed raw materials into manufactured products to be shipped east or sold inside the booming city.

Pilsen quickly became densely populated. But with frequent floods along the waterways and most residents too poor to afford indoor plumbing, illnesses spread quickly and took a fierce toll. Cholera outbreaks in the 1850s and ’60s claimed hundreds of lives. Anyone who could afford to move fled to higher ground and more sanitary conditions.

But new waves of immigrants were always ready to take their place. They came from Germany, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Italy, among other places. The Czech population dominated, as thousands fled the Austrian Empire seeking political and religious freedom. A popular, nostalgic Czech Bohemian hangout, a restaurant named At the City of Plzeň, gave the neighborhood its name.

Although the Czech arrivals constructed their own church, St. Procopius, not all of the Czechs were churchgoers. Many more were Bohemian Freethinkers, agnostics who valued reason and logic over tradition and church doctrine. In 1870, they formed a secular institution, The Congregation of Bohemian Freethinkers of Chicago, or Svobodna obec Chicagu. It served many of the same social functions as a church, conducting weddings and secular baptisms and becoming a social nexus for Pilsen’s Freethinker community, eventually creating an extensive network of schools, athletic clubs (or sokols), benevolent societies, organized discussion groups, and forums for political debate. When a Pilsen church refused to hold a mass for one of their members, they established their own cemetery on Chicago’s North Side.

Downtown banks at the time refused to loan money to blue-collar workers, so the Freethinkers formed their own credit unions and savings and loan associations, providing the means for much of Pilsen’s earliest and grandest development projects. To this day, the favored neo-Bohemian baroque architecture, marked by heavily-corniced, mixed-use structures, defines the neighborhood’s unique aesthetic.

Malleable Iron Works from 24th Street and Western Avenue. Courtesy of Roosevelt University’s Archives

In 1871, the Great Fire of Chicago largely spared Pilsen but devastated much of the rest of the city. Cyrus McCormick, whose reaper invention had already begun to revolutionize agriculture, was one of many who lost his business in the blaze. But he and other industrialists soon rebuilt in Pilsen, along the river. His factory, at what is now 22nd Street and Western, soon employed 800 men. Meanwhile, rapid reconstruction throughout Chicago accelerated the growth of several industries, including lumber. The Pilsen Yards, at today’s 22nd Street and Blue Island, became the largest lumber distribution center in the world.

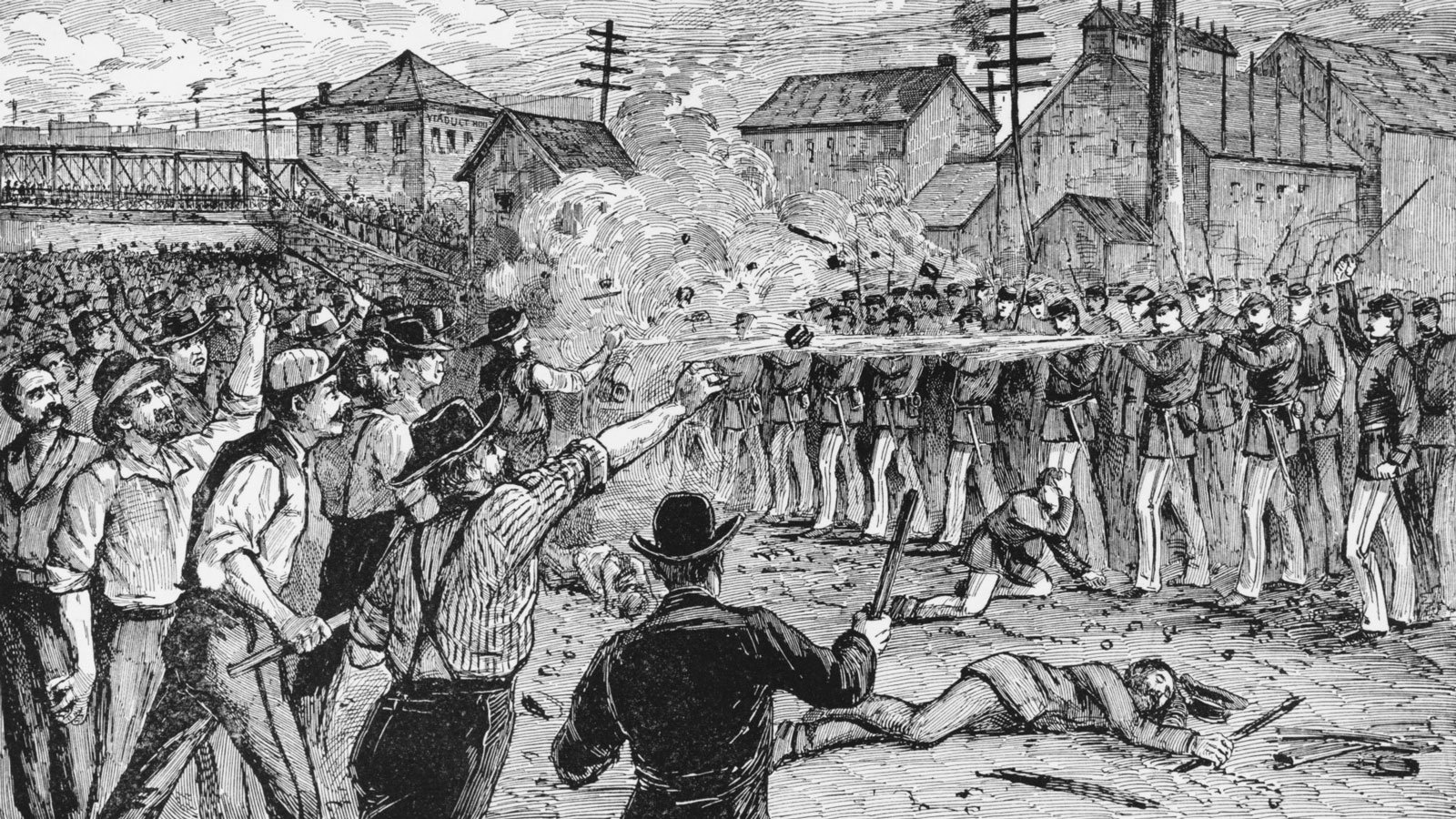

Pilsen’s growing industrial labor force was underpaid and overworked, with even children made to work ten-hour days, six days a week. Socialism, anarchism, and workers’ unions flourished. In 1877, national railroad strikes inspired a massive labor uprising. Demonstrators marched down Halsted, calling upon all workers to leave their posts and join the revolt. The lumber yards, meat processing plants, iron works, and furniture factories all ground to a halt. The demonstrations lasted for days. Mayor Monroe Heath ordered all saloons to close. Eventually, he called in federal troops and the state militia to help the Chicago police suppress the demonstrations. On July 25, violence erupted near the Halsted Street viaduct. Authorities killed at least thirty strikers and wounded dozens more.

The Labor Troubles of 1877, riots at the Halsted Street viaduct in Chicago. Courtesy of Roosevelt University’s Archives

But the seed of rebellion had been planted. Labor unions continued growing in size and strength. During a McCormick workers’ strike a decade later for an eight-hour day, police, who were providing security for the strikebreakers, fired into the crowd, killing between two and six people (accounts vary) and setting off a chain of events that culminated in the Haymarket Affair.

As awareness grew among Chicago’s elite about the plight of the immigrant workers, sympathizers started seeking ways to align themselves with the struggle to alleviate poverty. Inspired by the settlement movement in England, the middle class and well-educated established homes where they could live among the poor, teach literacy and job skills, and offer childcare and other services.

In 1889, just north of Pilsen, Jane Addams co-founded the first settlement house in the U.S. Soon thereafter, churches and civic-minded people opened several other settlements in predominantly low-income neighborhoods. In 1898, Gads Hill Center opened in a former Pilsen saloon. It moved to its current home at 1919 W. Cullerton in 1916, where it continues to provide educational opportunities and social services for local residents.

Women collect scrap wood from the Yards. Courtesy of Roosevelt University’s Archives

Pilsen continued to be home to a mainly blue-collar Bohemian population for decades. However, after Czechoslovakia gained independence in 1918, there were far fewer new arrivals. The immigrant population aged and continued working in the factories, while many of their children grew older and sought to more fully assimilate into American life.

In time, the Great Depression and World War II began to strain community and individual resources, and Chicago’s industrial boom began to sputter. The blue-collar jobs that created Pilsen began moving to the suburbs. Many workers went with them, leaving the shells of abandoned factories in their wake. Pilsen’s population declined from approximately 66,200 in 1930 to 48,400 in 1960. The neighborhoods that circle the Loop, including Pilsen, slowly became synonymous with crime, urban decay, and poverty.

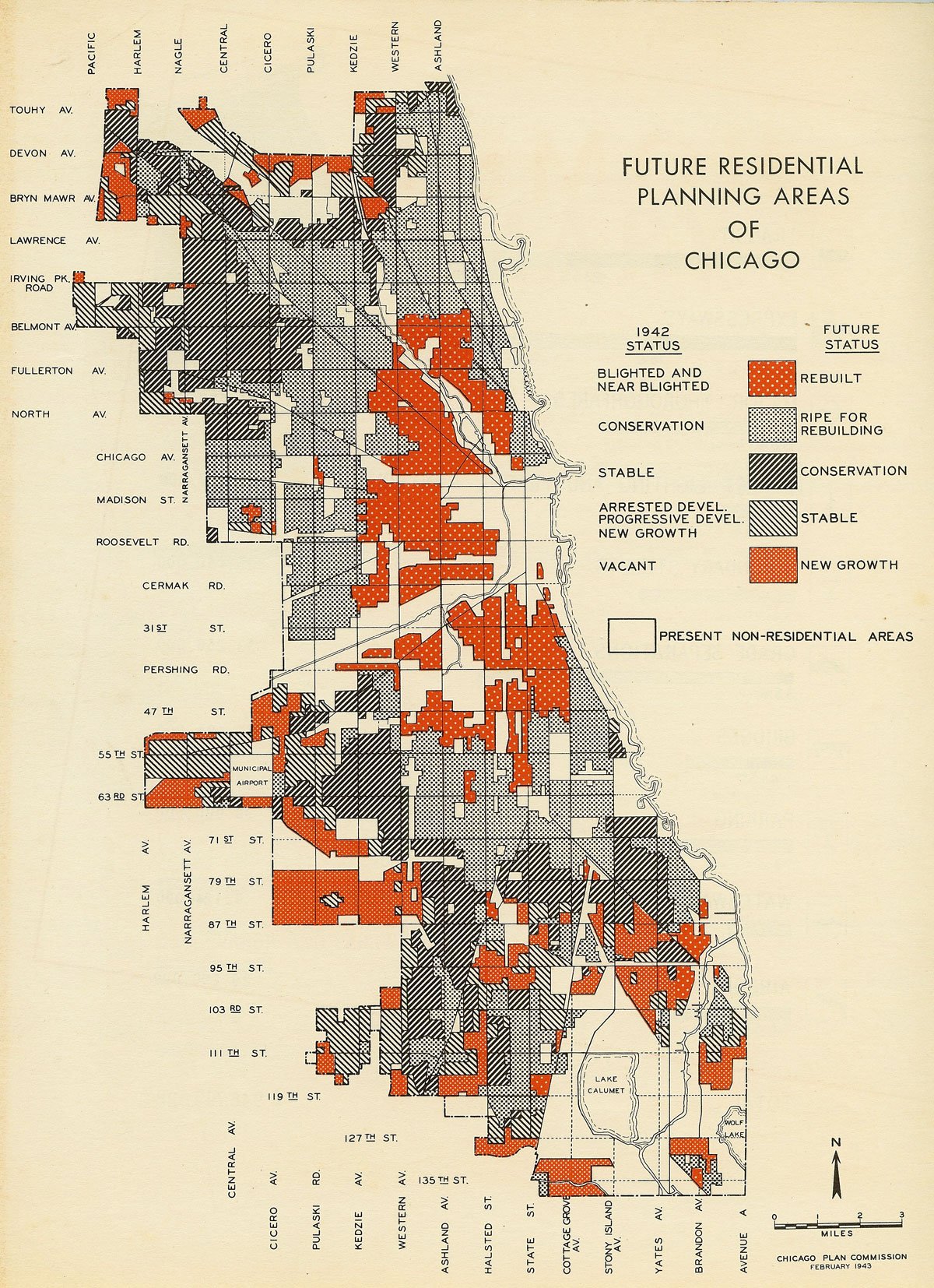

Meanwhile, across the country, urban renewal programs gained widespread popularity among city planners and developers. A spate of local, state, and federal laws in the 1940s and ’50s created multiple funding streams to incentivize projects that would displace low-income residents, demolish dilapidated structures, and rebuild in the most blighted urban areas. In Chicago, business and civic leaders began devising a series of projects that would essentially create suburbs, or “residential planning areas,” within city limits. Nearly all of the areas they targeted for redevelopment were occupied by predominantly poor and non-white people.

With the election of Mayor Richard J. Daley in 1955, the proponents of urban renewal gained their greatest ally.

Future Residential Planning Areas of Chicago, 1954. As part of the Chicago Plan Commission, Chicago Looks Ahead. Courtesy of the Chicago Plan Commission

It began with the construction of the Stevenson Expressway in the mid-1950s. That project displaced many lower-income Chicagoans from the Near West Side, including several Mexican families. They moved just south to the area surrounding Hull House. There, they joined an ongoing grassroots movement of black, Latino, and Italian-American residents hoping to leverage urban renewal policies to secure safer, more dignified affordable housing units in their existing neighborhoods. They had already secured “blighted” status for the area surrounding Harrison and Halsted, unlocking government-backed loans and other funding streams and triggering eminent domain laws that could force the removal of residents. They were in discussions with city officials and drafting plans for a new, mixed-use affordable housing project on the site. The Chicago Land Clearance Commission began appraising and purchasing lots, and residents began moving out.

Meanwhile, in separate meetings, the mayor, the city’s planning commissioner, and a member of the Hull House Board of Trustees were simultaneously developing other plans for the site. In September 1960, Mayor Daley proposed that the University of Illinois (UIC) build its new downtown campus at the precise location of the proposed affordable housing units, as well as several adjacent acres. The neighborhood coalition fought fiercely – with demonstrations and a lawsuit – but ultimately lost.

In the end, an estimated 5,000 people were displaced to make way for UIC. Several Mexican families moved south to nearby and affordable Pilsen, kicking off a wave of migration that would change the face, character, and trajectory of the neighborhood.

In 1960, approximately 14 percent of Pilsen’s population was Mexican or of Mexican descent. Within a decade, they comprised the majority of Pilsen residents.

Many of the predominantly blue-collar Polish residents who had called Pilsen home for generations and were, like much of Chicago at that time, struggling financially met the newcomers with bare-faced fear and loathing. Within a generation, most of the Polish residents fled westward – first to Little Village and later to the suburbs.

Local Catholic churches were the first established institutions to open their doors to the Latino newcomers. In 1963, St. Pius V became the first parish to offer mass in Spanish – though it was held in the basement.

But soon the Mexicans in Pilsen began claiming space for themselves – not only in the main sanctuary, but also in the local organizations, shops, and other institutions. First, Mexican activists assumed leadership roles in the Pilsen Neighbors Community Council, a civic organization founded just a decade earlier to defend Pilsen from a separate urban renewal scheme.

They began marking their territory with vibrant and often confrontational murals, beginning with Mario Castillo’s Peace (also known as Metafisica), an anti-war mural he painted along Halsted and Cullerton Streets in 1968. Soon, other artists began painting their history and the revolutionary history of the Mexican people, on the sides of the buildings and along the viaducts.

Peace (Metafisica) by muralist Mario Castillo. Courtesy of Mario Castillo

And they began challenging more established institutions. In 1969, several emerging Latino leaders in Pilsen began criticizing Howell House, a local settlement house that opened in 1905, for failing to meet the needs of the changing community. In 1970, they succeeded in renaming the building Casa Aztlán, in reference to the Chicano power movement, which was gaining strength across the country. Soon after, the church-based funders pulled out and Mexican and Mexican-American activists took over the building wholesale. The Brown Berets, an organization allied with the Black Panther Party, took the lead, turning it into a completely independent hub of community and political organizing. They ran it with an all-volunteer staff and provided affordable housing for artists and activists, a free clinic for local residents, and a meeting space for throngs of young radicals.

In 1971, a group of women felt that the movement was too male-dominated, so they created their own space, Centro de la Causa, with the support of the Catholic Church. According to a Chicago Tribune article, for decades it provided “a refuge for Pilsen's needy, a place where a teenager could duck in for basketball or where single mothers could go for baby formula, Thanksgiving meals or advice on how to keep their lives in gear.” In 1973, they hosted a regional Latina women’s conference at Centro de la Causa.

They and others monitored the stated goals of area foundations and city leaders, quickly applying for funds and exerting political pressure to secure them. Their movement grew.

In those days, Spanish-speaking students were placed in special education classes in lieu of bilingual education, and the local schools didn’t employ Latino teachers or support staff. In 1969, several local high school students at the Froebel extension of overcrowded Harrison High, working in collaboration with their African-American classmates, organized massive walkouts to demand better conditions.

Soon, parents were also rallying. They sent busloads of supporters to demonstrate at Chicago Public Schools headquarters and held sit-ins. In 1973, the school board approved the construction of a new high school in the Pilsen neighborhood. But it took time and continued pressure to bring their vision to fruition. Benito Juarez Community Academy finally opened its doors on September 16, 1977.

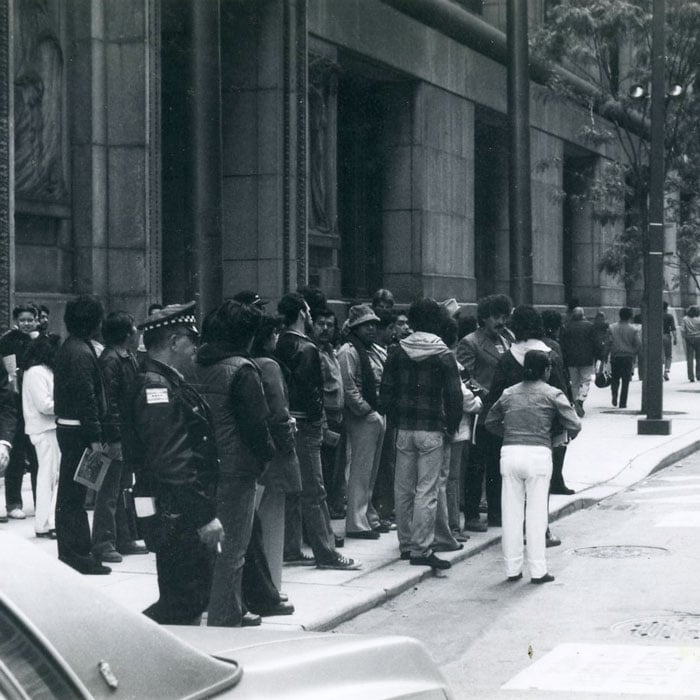

Benito Juarez High School planning meeting, circa 1973-1977. Courtesy of Teresa Fraga and Special Collections and Archives at DePaul University Library, Chicago, IL

Around the same time that the movement for a community high school was reaching a climax, activists at Casa Aztlán were tipped off to another major urban renewal plan in the works for East Pilsen and other communities near the Loop. The Chicago 21 Plan, developed by the Chicago Central Area Committee (CCAC), a coalition of downtown business leaders, aimed to replace the old industrial areas to the south and east of Pilsen with middle-class communities, replete with commercial centers, schools, churches, and an estimated 68,000 new residents. With the memory of the UIC displacements fresh in their minds, the Mexican community mobilized. They forged unprecedented alliances with leaders in other predominantly African-American and Latino communities slated for redevelopment as part of Plan 21 – including Cabrini and East Humboldt Park – none of whom had been consulted in the plan’s creation.

The fight against Plan 21 was in many ways a defining moment in Pilsen’s history. Leaders at the Pilsen Neighbors Community Council and Casa Aztlán were joined by 18th Street business owners and local church leaders in a movement to oppose development imposed upon them from the outside and to develop strategic plans for what community-led revitalization efforts might look like.

They formed Pilsen Community Planning Council and demanded a meeting with the city’s commissioner of development and planning. They showed up uninvited to a CCAC luncheon where the plan was to be unveiled, making sure their faces were seen and their voices were heard.

Members of the community arrive on buses and spill into the streets to protest Plan 21. Courtesy of Teresa Fraga and Special Collections and Archives at DePaul University Library, Chicago, IL

The actions made it known among city power brokers that the activists of Pilsen were organized, aware, and ready to defend what they had built.

In a press release dated April 8, 1974, the alliance of community activists, organized as the Coalition of Central Area Communities, stated: “We want to revitalize our neighborhoods, and we too want a strong central area. But we recognize that the buildings sketched in the plan are not for us….We know the history of what development means in the city of Chicago. For us, urban renewal has meant urban removal. But we intend to stay where we are living now.”

The community eventually convinced the CCAC to go back to the drawing board, and Plan 21 was never realized as it was originally crafted.

Fresh victories in creating a new high school and halting outside development galvanized and solidified Pilsen’s activist community and, for a time, created an electrifying momentum. Everything seemed possible.

In 1973, a group of Pilsen mothers, frustrated that their children with special needs weren’t being served in the public school system, began an ad-hoc school and social service agency. It later became El Valor, an agency that today employs more than 300 people to empower, educate, and provide opportunities to people with disabilities and their families.

In 1974, a group of feminist women allied with Centro de la Causa opened a drop-in center for teenaged runaways. For years, they paid rent on a small storefront by hosting regular parties. Mujeres Latinas En Acción would go on to create a domestic violence shelter, self-defense classes, and a range of social services and advocacy around women’s health and female empowerment that continue to this day.

It took many years and many more setbacks, struggles, and campaigns before Pilsen’s transformation became measurable. Poverty, gang violence, and a lack of education – particularly in a community with a large undocumented population – are not problems that are solved overnight. Indeed, many of these battles are still being fought today.

And so are new battles. As the neighborhood’s amenities, opportunities, and safety have improved, Pilsen has gentrified, becoming increasingly attractive not only to a growing Latino middle-class, but also to non-Latino populations, real estate developers, and businesspeople. Many long-time residents say Pilsen, as they have long known it, is under assault.

But Pilsen has a long history of fighting back.

What follows are the stories of just some of the people who continue that fight: environmentalists struggling to clean the legacy of polluting industries; organizers working to preserve the affordability and character of the neighborhood; immigrant advocates fighting for security and opportunity for all, regardless of their legal status; and educators working daily to give the younger generation the tools they need to fight the battles they are inheriting.

– Jessica Pupovac