Jobs | My Neighborhood: Pilsen

Jobs

A panel of Increíbles Las Cosas Que Se Ven, a mural by Mark Zimmerman depicting different working class citizens. Photo by Kaitlynn Scannell

Magda Ramirez-Castañeda still knows how to rally a crowd. At a recent anti-gentrification event at Rudy Lozano Library in Pilsen, the longtime rabble-rouser reminded young activists of the victories won by their predecessors.

“You see Latinos driving the CTA busses?” she asked them. “That wasn’t happening before. That changed because people like us did something about it.”

She didn’t elaborate, but many there smiled and nodded knowingly. Ramirez-Castañeda, co-author of Chicanas of 18th Street, is a living legend in Pilsen.

In 1972, she and other activists, along with the Asociación Pro Derechos Obreros, or the Association for Workers’ Rights, orchestrated a series of demonstrations against the Chicago Transit Authority, demanding the agency hire more Latino drivers. They blockaded busses along 18th Street and, on more than one occasion, boarded them, told riders to leave, and occupied them.

One of their demonstrations grew particularly confrontational, leaving several people injured, including police officers.

It wasn’t the first time things got violent during a labor struggle in Pilsen. Workers’ demonstrations turned deadly during both the 1877 Battle of the Viaduct and later, during a strike at the McCormick Reaper Works, where workers were fighting for an eight-hour day. But those dramatic struggles claimed historic victories. According to the late labor historian William Adelman, it was in Pilsen that collective bargaining and arbitration were first used, back in the 19th century, “but only after the shedding of a great deal of blood.”

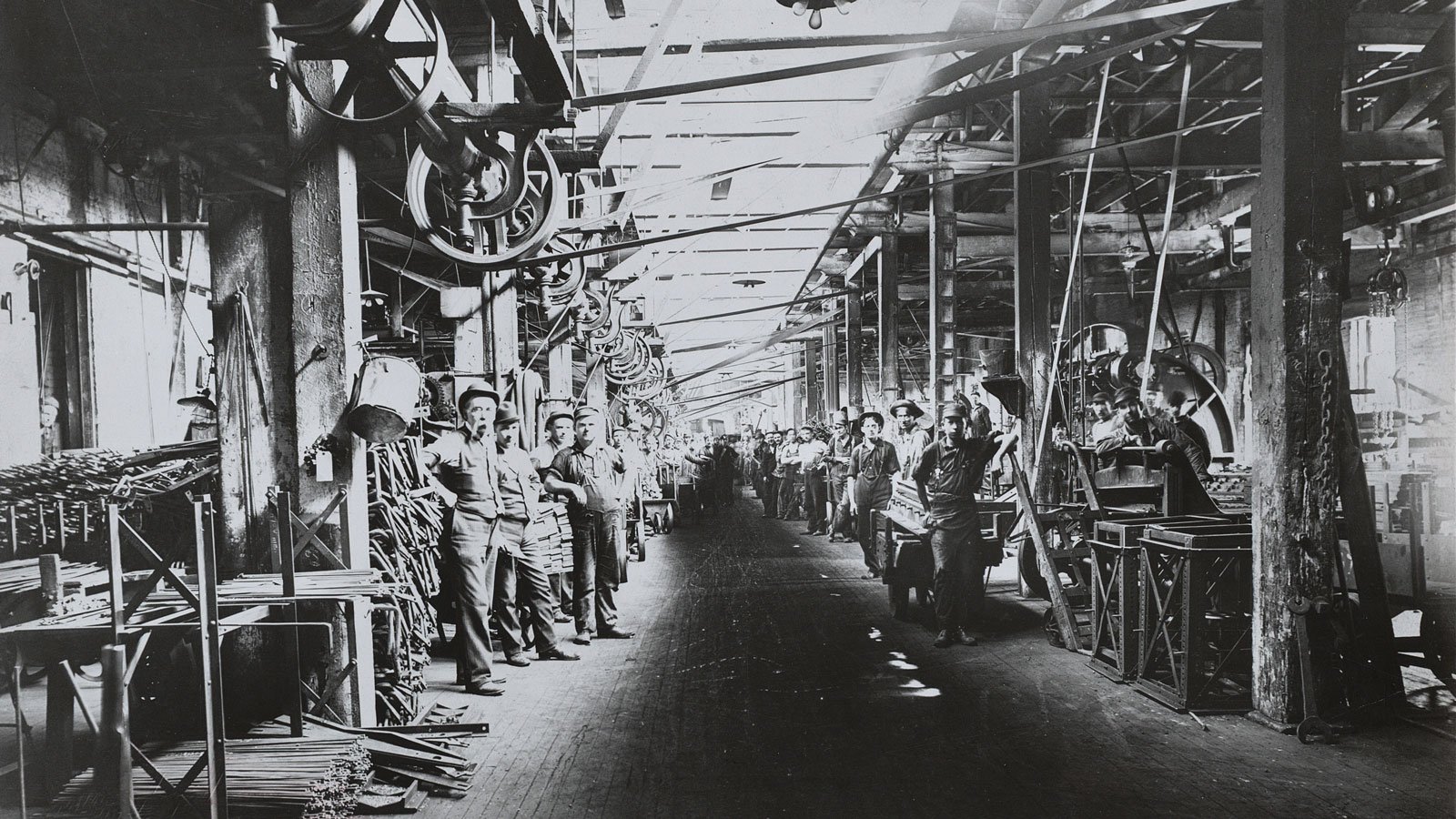

Workers at McCormick Factory. Courtesy of Roosevelt University’s Archives

The Mexican population that has dominated Pilsen since the 1970s has continued to fight for labor justice. Demonstrations like the ones against the CTA continued throughout the ’70s, directed at several agencies and companies that, at that time, hired few Latinos, if any. They included the Chicago Fire Department, the U.S. Post Office, Greyhound, and Jewel, among others.

Other Pilsen activists have taken different approaches, training residents in trades that might crack open job opportunities. The Pilsen Neighbors Community Council launched its Rehab Project in the mid-1970s with the joint goal of training community youths in building and construction skills and improving the housing stock in Pilsen.

In 1976, that initiative spun off into the Eighteenth Street Development Corporation, which started teaching bricklaying skills and eventually expanded its mission to work directly with employers in the industrial corridor, downtown, and elsewhere advocate for employing Pilsen residents.

In 1981, tradeswomen feeling out of place in the “brotherhood” formed Chicago Women in Trades to create more opportunities for women in carpentry, pipefitting, and other union positions traditionally dominated by men.

More recently, organizations such as Instituto del Progreso Latino have finely tuned their educational programs to better prepare students for jobs in high-demand fields that pay a living wage.

And organizations such as Blue 1647 have opened up shop in Pilsen, introducing high-tech and entrepreneurial skills to the neighborhood’s job training opportunities.

In recent years, Alderman Danny Solis has endeavored to draw more industry back to Pilsen through the creation of the Pilsen Industrial Corridor Tax Increment Financing District, which incentivizes development through cleaning up after or remodeling old factories, building new ones, and providing funding for job training and readiness programs.

Today, approximately 12 percent of Pilsen residents are employed in manufacturing. Still, many more Pilsen residents own or work at low-wage jobs in the service industry along 18th Street – at the bodegas, butchers, restaurants, and bars that provide the center of the Pilsen economy.

Many of these smaller industries pay too little to allow for upward mobility. Indeed, although much of Pilsen is employed, many more are employed in low-paying jobs than the citywide average.

Poverty Rate in Pilsen and Chicago

Pilsen Jobless Rate by Year

Data Sources: 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Decennial Censuses and 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-year Estimates

Still, there are signs of progress. The number of residents in managerial positions has increased over time, from about 7 percent in 1970 to 23 percent in 2010. Still, it is unclear who are occupying those upper level positions, and whether they are upwardly mobile long-time residents or new arrivals.

There is now a wide discrepancy in per capita income between Latino and Pilsen’s growing number of white residents, a discrepancy which is particularly pronounced in census tracts on the east side of the neighborhood, dubbed the Chicago Arts District by developer John Podmajersky Jr.

Pilsen White and Hispanic Median Household Income

Source: analysis by Bentacur, John and Kim, Youngjun, “The Trajectory of Ongoing Gentrification in Pilsen,” University of Illinois Chicago.

One way that organizations like Pilsen Alliance have responded to this reality is by working to increase the minimum wage. In 2015, they canvassed heavily to get out the vote in support of increasing the minimum wage from $8.25 to $10 per hour in Illinois. Although Cook County voted overwhelmingly in support of the referendum, it did not pass at the state level.

That struggle, like many others, continues.