Victorian Cooking with Francatelli

Daniel Hautzinger

February 23, 2017

Find all of our Victoria content here, including episode recaps and other features.

If you want to dine like a queen after seeing the opulent desserts on Victoria, you can turn to Charles Elmé Francatelli. Played by Ferdinand Kingsley on the Masterpiece series, Francatelli was a real-life chef who served as Maìtre d’hôtel and Chief Cook to Her Majesty the Queen Victoria from 1840-1842. Four years after leaving the Queen’s service to become chef at one of the most popular dining clubs of the day, he published a book called The Modern Cook that, in addition to recipes for haute French cuisine, included menus that he served at the palace.

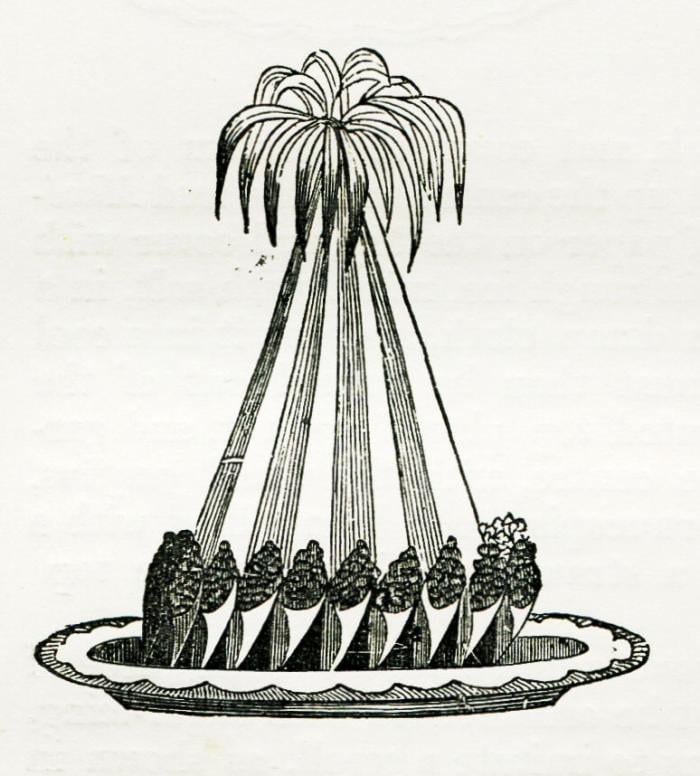

Iced Pudding a la Chesterfield from Francatelli's "The Modern Cook," with ice cream cones around the base.The Queen’s meals were elaborate affairs, consisting of eight or more courses, with multiple dishes per course in addition to a buffet or side board. Francatelli presented dishes with an eye for visual impact, aiming to stun guests with fantastic presentations such as colorful jellies, massive pies, and whole birds and fish. One pudding recipe even features the first printed instance of ice-cream cones: rolled wafers filled with pineapple ice cream ornament the base of the dish.

Iced Pudding a la Chesterfield from Francatelli's "The Modern Cook," with ice cream cones around the base.The Queen’s meals were elaborate affairs, consisting of eight or more courses, with multiple dishes per course in addition to a buffet or side board. Francatelli presented dishes with an eye for visual impact, aiming to stun guests with fantastic presentations such as colorful jellies, massive pies, and whole birds and fish. One pudding recipe even features the first printed instance of ice-cream cones: rolled wafers filled with pineapple ice cream ornament the base of the dish.

The Modern Cook features expensive ingredients and complicated, labor-intensive recipes that would be impossible for most domestic cooks of the time to prepare. But it did establish a two-course meal as the standard for lunch and dinner, popularized French cooking styles, and sold extremely well in both England and America, where wealthier households sought to imitate the queen.

Francatelli eventually published three other cookbooks while working at a variety of esteemed London establishments, making him the Victorian equivalent of a celebrity chef. His 1852 A Plain Cookery Book for the Working Classes sought to establish him as a mainstay in poorer households, with recipes that give “the greatest amount of nourishment at the least possible expense.”

(ITV Plc)A Plain Cookery Book is filled with ways to stretch food. One recipe is for “Economical Pot Liquor soup,” which adds oatmeal and spices to the liquid from boiled beef, while “Thick Milk for Breakfast” mixes milk, flour, and salt into a delicious gloop to be served with bread or a potato. Francatelli advises the reader that, although “Swedish turnips are mostly given as food to cattle...there is no good reason why they should not be considered as excellent food for man.” And the book ends with a section on “Economical and Substantial Soup for Distribution to the Poor,” which is basically broth made from the less desirable parts of an animal – heads, organs, shanks, “scrag-ends” – with some vegetables, grain, and small pieces of meat thrown in.

(ITV Plc)A Plain Cookery Book is filled with ways to stretch food. One recipe is for “Economical Pot Liquor soup,” which adds oatmeal and spices to the liquid from boiled beef, while “Thick Milk for Breakfast” mixes milk, flour, and salt into a delicious gloop to be served with bread or a potato. Francatelli advises the reader that, although “Swedish turnips are mostly given as food to cattle...there is no good reason why they should not be considered as excellent food for man.” And the book ends with a section on “Economical and Substantial Soup for Distribution to the Poor,” which is basically broth made from the less desirable parts of an animal – heads, organs, shanks, “scrag-ends” – with some vegetables, grain, and small pieces of meat thrown in.

There are fancier recipes too, for special occasions or families with more means. Tripe is an exciting indulgence for a birthday or holiday. If you have a spare large bird to eat, you can make “Cocky Leeky,” a soup with chicken, leeks, and rice, or dress a roast fowl with egg sauce, which is a gravy of flour, water, and butter, bobbing with boiled eggs. On the occasions when “industrious and intelligent boys” catch some songbirds, Francatelli instructs them to pluck them, “cut off their heads and claws, and pick out their gizzards from their sides,” then to “hand the birds over to your mother” so she can make “A Pudding Made of Small Birds.”

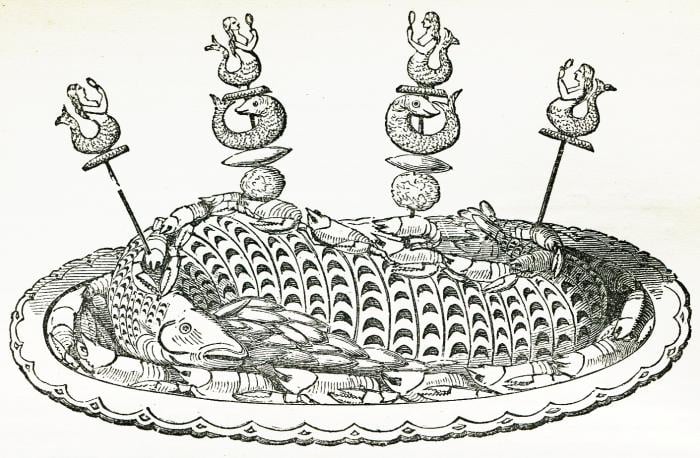

Salmon a la Chambord from Francatelli's "The Modern Cook." Francatelli’s books also provide fascinating glimpses of culinary life during a period in transition to the modern era. While many of the recipes in A Plain Cookery Book instruct you to boil your food since many households did not have an oven, when you want to prepare a bullock heart or some sheep’s heads, baking is recommended. If you don’t have an oven, just send it to the baker and they’ll do it for you. Though broilers did not yet exist, you could hold a red-hot shovel above a dish to melt cheese over oysters. There is a recipe using curry powder (newly abundant as an import from Britain’s colonies), a call to cook with green beans and lentils (uncommon in England, but staples of the French diet), and instructions for making coffee (an exotic import first introduced in the 17th century).

Salmon a la Chambord from Francatelli's "The Modern Cook." Francatelli’s books also provide fascinating glimpses of culinary life during a period in transition to the modern era. While many of the recipes in A Plain Cookery Book instruct you to boil your food since many households did not have an oven, when you want to prepare a bullock heart or some sheep’s heads, baking is recommended. If you don’t have an oven, just send it to the baker and they’ll do it for you. Though broilers did not yet exist, you could hold a red-hot shovel above a dish to melt cheese over oysters. There is a recipe using curry powder (newly abundant as an import from Britain’s colonies), a call to cook with green beans and lentils (uncommon in England, but staples of the French diet), and instructions for making coffee (an exotic import first introduced in the 17th century).

In addition to coffee, Francatelli has recipes for some other familiar drinks – ginger beer, lemonade, beer – as well as stranger ones: an “Egg-hot” made of warm beer with an egg, sugar, and nutmeg, or “Toast Water,” a drink for invalids that is exactly what you think it would be. But better toast water when you’re sick than “Stringent Gargle”: a mixture of sage leaves, rose leaves, water, vinegar, and honey, “to be used when cold.” It’s not quite a dish fit for a queen.