Chicago's First Mexican Church

Daniel Hautzinger

September 20, 2017

Mexican Independence Day is September 16, in celebration of the day in 1810 that the Catholic priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla instigated the Mexican War of Independence against the Spanish by ringing his church bell and proclaiming a call to arms. But it was another uprising a century later that brought the first influx of Mexican migrants to Chicago.

In 1910, after the authoritarian General Porfirio Díaz won another term as president of Mexico in a fixed election – he had been in power for over three decades – a Revolution broke out, leading to the adoption of a new Constitution in 1917. While the Revolution achieved important reforms – the Constitution, still in place today, was a groundbreaking and influential enshrinement of rights that inspired later revolutionaries around the world – it also was a time of great upheaval. Catholics faced religious persecution as the government embraced secularism and anti-clericalism, especially in the 1920s. This unrest led many Catholic Mexicans to turn north for employment.

Steelworkers in ChicagoThey were encouraged by the United States government, which passed a stringent immigration law in 1917 that restricted European and Asian migrants but made an exception for Mexican workers, who were needed to fill jobs on railroads, on farms, and in factories as the country entered World War I. Mills, packinghouses, and railroads sent enganchistas, labor recruiters, to the border to entice workers, generally lone males known as solos, north to cities like Chicago. From 1910 to 1920, Chicago’s Mexican population ballooned from 102 to 1,224 – and those figures are probably low.

Steelworkers in ChicagoThey were encouraged by the United States government, which passed a stringent immigration law in 1917 that restricted European and Asian migrants but made an exception for Mexican workers, who were needed to fill jobs on railroads, on farms, and in factories as the country entered World War I. Mills, packinghouses, and railroads sent enganchistas, labor recruiters, to the border to entice workers, generally lone males known as solos, north to cities like Chicago. From 1910 to 1920, Chicago’s Mexican population ballooned from 102 to 1,224 – and those figures are probably low.

Many of those laborers did not intend to settle in Chicago permanently; rather, they sought to find seasonal work there or stay until things calmed down back in Mexico. They faced housing discrimination, being forced to pay higher rents and live in close quarters. Some workers, especially the traqueros, railroad workers, lived in boxcars. Soon colonias, Mexican enclaves, were being established on the Near West Side, in Back of the Yards, and in South Chicago.

It was in the last neighborhood that immigrants founded Chicago’s first Mexican church. By the mid-1920s, the nearby steel mills employed more than 6,000 Mexicans. While a few received permanent positions in the lowest-paying jobs, most had to show up outside the mill every morning, hoping to be chosen for work that day. Despite the tenuousness – and danger – of the work at the mills, wives and families began to join the solos. As families set down roots and migrants continued to move in and out of the city, the Mexican community of South Chicago sought to establish a religious center. Other churches turned away Mexicans, who were often not welcome beyond the borders of their colonia.

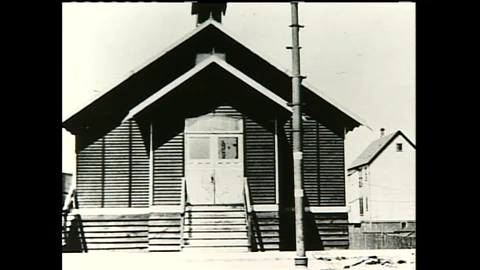

The army barracks that originally housed Our Lady of GuadalupeIn 1924, the Catholic Father William Kane arranged for an old, one-room barracks to be brought down from southern Michigan to serve as a worship space for the Mexicans of South Chicago, and Our Lady of Guadalupe was founded. When Father Kane retired, the church was entrusted to the Claretians, a religious order founded in Spain. Many of the Claretians had served in Mexico and fled the anti-clerical persecution there just like some of the families who now lived in Chicago. Priests like Father James Tort could therefore relate to the experience of their Mexican parishioners.

The army barracks that originally housed Our Lady of GuadalupeIn 1924, the Catholic Father William Kane arranged for an old, one-room barracks to be brought down from southern Michigan to serve as a worship space for the Mexicans of South Chicago, and Our Lady of Guadalupe was founded. When Father Kane retired, the church was entrusted to the Claretians, a religious order founded in Spain. Many of the Claretians had served in Mexico and fled the anti-clerical persecution there just like some of the families who now lived in Chicago. Priests like Father James Tort could therefore relate to the experience of their Mexican parishioners.

The parish quickly outgrew the cramped barracks, so a new church was dedicated and built in 1928. Unfortunately, the advent of the Great Depression reversed the fortunes of the burgeoning Mexican community. As unemployment soared after 1929, Mexicans were often the first people to lose their jobs. Worse, eager to appear as if it were doing something to ease the Depression, the government began forcibly deporting and repatriating Mexicans back to Mexico regardless of their citizenship in the U.S., arguing that they were stealing the jobs of white Americans. During the ‘30s, the Mexican population in Chicago was nearly halved.

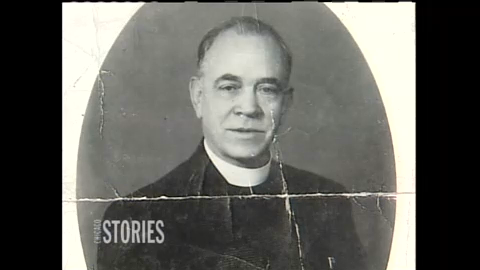

To aid the parishioners who managed to stay in Chicago but suffered from unemployment and poverty, Father Tort began praying to St. Jude, building an altar to the patron saint of hopeless causes. He established Our Lady of Guadalupe as the National Shrine of St. Jude, and visitors were soon appearing from around the country to pay their devotions and give donations.

Father James Tort, the Claretian who established the National Shrine of St. Jude at Our Lady of GuadalupeOur Lady of Guadalupe also provided financial support to unemployed parishioners. Meanwhile, Mexican steelworkers were playing an integral part in unionization efforts. The official recognition of the steel union in 1937 helped Mexican laborers gain more equality and chances of promotion in the mills.

Father James Tort, the Claretian who established the National Shrine of St. Jude at Our Lady of GuadalupeOur Lady of Guadalupe also provided financial support to unemployed parishioners. Meanwhile, Mexican steelworkers were playing an integral part in unionization efforts. The official recognition of the steel union in 1937 helped Mexican laborers gain more equality and chances of promotion in the mills.

During World War II, the U.S. again encouraged the migration of Mexican laborers, bringing some 15,000 braceros, guest workers, to Chicago between 1943 and 1945 under an agreement with the Mexican government. Once again, however, the U.S. reversed its position and began deporting and repatriating Mexicans under “Operation Wetback,” implemented in 1954. During the Vietnam War, Our Lady of Guadalupe lost more soldiers in combat than any other Catholic parish in the country. Eventually, the steel industry in South Chicago declined, with the mill completely closing in 1992.

While the South Chicago and Back of the Yards Mexican communities continued to exist in the postwar period, the residents of the Near West Side colonia were displaced by the construction of the Stevenson Expressway and of the University of Illinois at Chicago. Many residents of the neighborhood moved south to Pilsen. By 1960, Mexicans made up the majority of residents there. Today, Pilsen and the neighboring Little Village are seen by many as the epicenters of the Mexican community in Chicago. But their roots were first established a century ago on the far south side, with a community that fought to work, live, and worship in a new city.