Chicago's 'Anarchist Queen'

Daniel Hautzinger

June 25, 2020

Meet other unsung pioneers from the turn of the twentieth century like Lucy Parsons in American Masters' Unladylike2020 digital videos.

“The common supposition is that Lucy Parsons is a virago, that when she talks she shrieks, that she strides instead of walking, that her daily diet is red fire,” wrote a reporter for Chicago’s The Inter Ocean in the summer of 1900. “Half of Lucy Parsons’ power is due to the fact that she is to the public, and even to her followers, a mythical terror.”

Across the country and especially in her home base of Chicago, a city filled with socialists and revolutionaries around the turn of the twentieth century, Parsons was infamous. Known as the “anarchist queen,” she fiercely railed against the oppressions of a capitalist system in essays and speeches. She was one of two founding women members of the powerful union the International Workers of the World, and the editor of various revolutionary publications. She supported widespread strikes in favor of an eight-hour workday and better treatment of laborers, and advocated for more radical tactics: in one famous essay, she exhorted homeless “tramps” to “Learn the use of explosives!”

While her husband, Albert Parsons, was one of the eight anarchists tried in connection with the disastrous Haymarket Affair and one of the four hanged for it, law enforcement may have considered Lucy just as threatening as him—if not more. The police “keep watch on her as they would a can of dynamite,” wrote The Inter Ocean. “When a riot call is turned in, the first supposition is that ‘Lucy is at it again.’ ”

Only some of her notoriety has survived her: sixty years after her death, when a Chicago park in the Belmont Cragin neighborhood was named after her, in 2004, the police union objected. Mayor Daley’s response showed just how much she has been forgotten, likely in large part because she was a woman: he defended the honor by saying it was unfair to blame her for the actions of her husband, completely missing her own radical views.

She may also have been discounted more than a century earlier because she was a woman. In 1886, prominent anarchists were rounded up after someone threw a bomb at police during an otherwise peaceful protest and the police responded with gunfire, in the disastrous Haymarket Affair. Although Albert Parsons wasn’t present at the gathering of anarchists when the bomb was thrown, he was still tried and convicted. Lucy, too, was arrested at the time—the police thought she knew where her husband was in hiding—but she wasn’t charged—probably because the chance that a woman would receive the death penalty was low, and the prosecution wanted severe punishment.

She traveled the country speaking about the injustice of the trial. (Illinois’s governor pardoned the surviving defendants in 1893 and criticized the trial.) When she tried to bring her two children to her husband’s hanging, the police prevented them from attending, instead bringing her to a cell and strip-searching her.

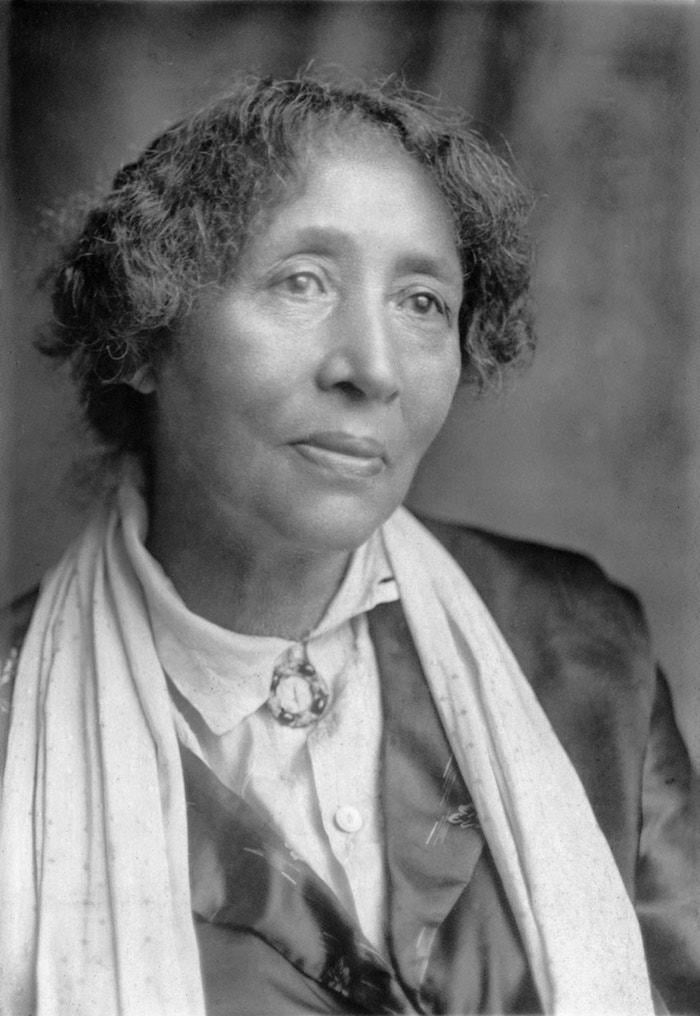

Lucy Parsons, perhaps in the 1920s. Photo: Wikimedia CommonsIt was far from her only run-in with the police. (“She is always getting herself arrested,” wrote The Inter Ocean.) She frequently arrived for a speech at a lecture hall to find the police waiting for her. She was an ardent champion of free speech and other rights; she published a journal called Freedom.

Lucy Parsons, perhaps in the 1920s. Photo: Wikimedia CommonsIt was far from her only run-in with the police. (“She is always getting herself arrested,” wrote The Inter Ocean.) She frequently arrived for a speech at a lecture hall to find the police waiting for her. She was an ardent champion of free speech and other rights; she published a journal called Freedom.

A certain amount of freedom was evident in her own life, despite the limitations on a woman like her at the time. Whereas Parsons always claimed to have been born in Texas to parents who were some combination of Mexican, Native American, or Spanish (her explanations shifted), she was in fact Black, born into slavery in Virginia around 1853, as Jacqueline Jones revealed in a recent myth-dispelling biography. Parsons never admitted it. She often went by the name Lucy Gonzales.

She married the white Albert Parsons in Texas, and the couple soon left for Chicago to escape anti-miscegenation laws and intense antagonism towards their radical politics. (Parsons claimed to The Inter Ocean that Albert was conservative when she met him, but that she dispelled the “old idea of religion” from him.) After Albert was fired from a printing job and blacklisted for organizing workers, Lucy supported the family as a seamstress, and, later, by selling chickens she raised as well as coffee and tea, according to The Inter Ocean, which delighted in pointing out the supposed inconsistency of the “bourgeoise [sic] surroundings” of Parsons’ home with her anarchist views.

While she supported the expansion of rights for women, she never really aligned herself with the suffragists, believing elections to be frauds controlled by the moneyed classes. “I regard the ballot thoroughly useless in adjusting class issues,” she wrote in the Chicago Tribune. “[T]he possessing or property classes will not relinquish what they consider their rights unless they are forced to do so.” She broke from other anarchists when they championed sexual freedom and the abandonment of marriage, even though Jones points out that Parsons had several lovers.

She politely criticized the social work of Jane Addams and others like her, and only touched on issues of race late in her life. Despite her claim to The Inter Ocean that, “Socialism is simply a school to graduate anarchists,” she eventually abandoned anarchists and joined the Communist Party. She owned her two-story home at 1777 North Troy Street on the Northwest Side and rented out the bottom floor.

“A strange creature is Lucy Parsons…” wrote The Inter Ocean. “One feels pretty sure after a talk with her that Kings and Queens and capitalists would be perfectly safe in her vicinity. She would make friends with them and loan them her lawn-mower. At the same time her talk might set fire to a powder mill and her friends might be burnt up in the explosion.”

Given all the fearful talk of fire and explosions that surrounded Parsons in the media, it is perhaps ironic that she died in an accidental fire in 1942, at the age of 89. After her death, the authorities seized her books and papers—part of the reason she is so little remembered today.

In the Inter Ocean profile of Parsons from 1900, the reporter at one point assures Parsons that he or she is trustworthy: “She was told she would not be misrepresented. ‘Oh, I don’t care,’ she said with a laugh and a shrug of her shoulders. ‘I’m used to it.’ ”