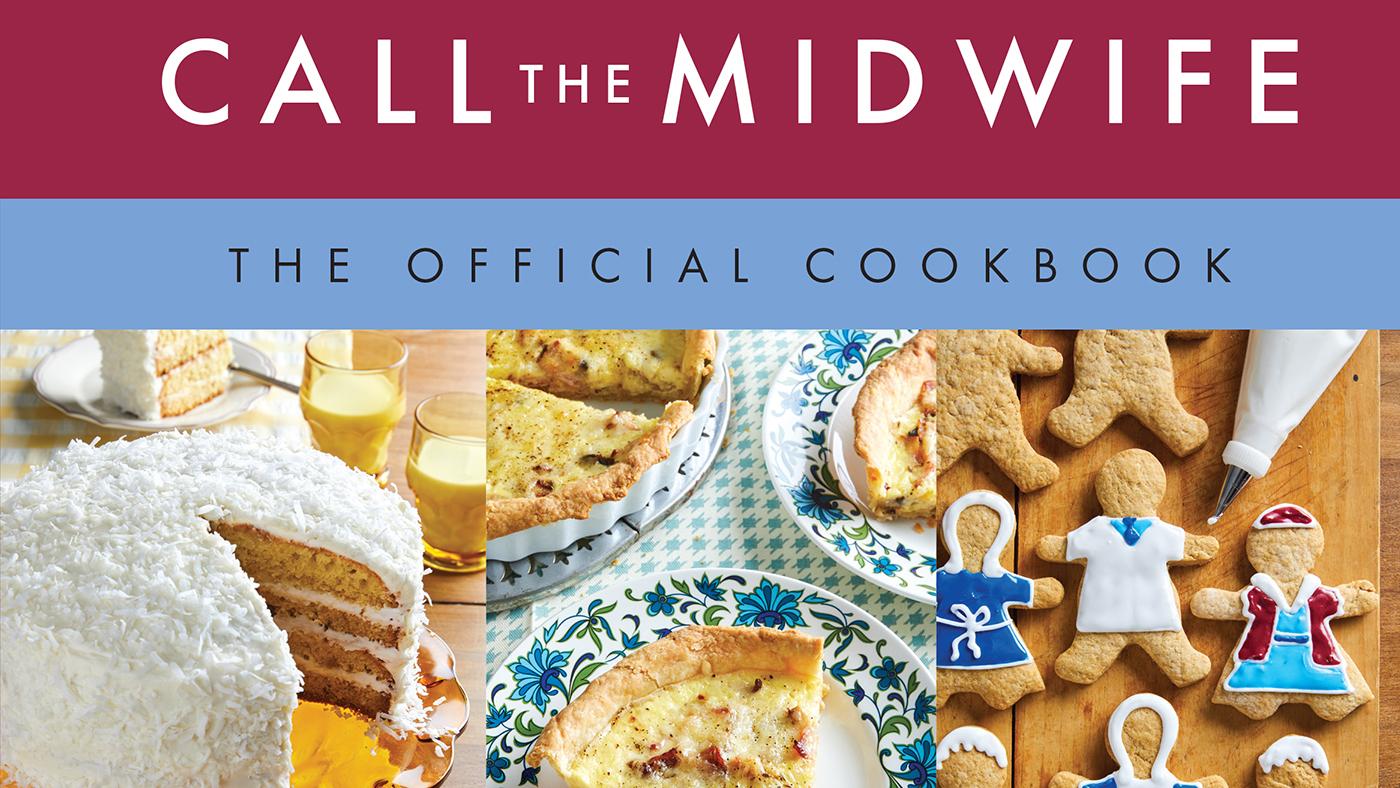

A 'Call the Midwife' Cookbook Explores the Food—and History—of a "Totally Bonkers Period"

Daniel Hautzinger

April 4, 2023

Get more recipes, food news, and stories by signing up for our Deep Dish newsletter.

Take an unsliced loaf of sandwich bread. Cut it horizontally into three long slices. Spread butter on each, then add your choice of different filling to every layer; suggestions are egg with mayonnaise, watercress with cottage cheese, and pureed chicken with almonds and cream. Reassemble the layers into a loaf, cover the whole thing in cream cheese as though you were frosting a cake, and decorate the top with flowers made out of vegetables. This is A Giant Sandwich Loaf.

“It’s just so crazed,” says Annie Gray, a food historian and author of the new Call the Midwife: The Official Cookbook, of the dish. “I had to put it in the book in the hope that someone does it and discovers that it’s a cacophony of every flavor under the sun, and yet, somehow, everyone starts smiling when they see it.” Even though it’s a sandwich, Gray advises eating it with a fork, given that it is slathered in cream cheese.

The cookbook provides recipes such as the sandwich loaf that were published in cookbooks in Britain during the time period in which Call the Midwife takes place, 1956-1970. “It’s a totally bonkers period,” says Gray. Rationing that had started during the Second World War only ended in 1954, so there was an exuberant joy in food and modern products—perhaps sometimes taken too far.

“There was this kind of reaction against the drabness and the monotony of the Second World War, and it just went crazy,” Gray says. “So you have food coloring in everything, silver balls on every possible surface, crazy, crazy food that towers up to the ceiling, an enormous embracing of convenience foods and shortcuts.”

Gray grew up in the 1980s, when a lot of food from the 1960s was still being served. “It was terrible,” she says. “But in every period you can find awful dishes, and in every period you can find joyous dishes. So what I wanted to do was take the spirit of the age and find the good recipes of the age and modernize them just enough that people could cook them very easily and take out some of the terrible things like food coloring and present them as something that’s still relevant and valid today.”

Despite the “sheer, utter ludicrousness” of some of the dishes of the era, Gray found plenty for the cookbook that “are genuinely, absolutely brilliant,” and have become staples in her own kitchen. There were even some surprises that meet in the middle, like peppermint sticks, minty rods made with cornflakes. “That sounds really wrong, and it is really wrong, but they’re delicious,” Gray enthuses.

Like Call the Midwife itself, which tackles serious, seldom discussed topics within the context of a hopeful, enjoyable show, Gray’s cookbook sneaks domestic history into people’s hands under the guise of light-hearted, entertaining recipes. (Another commonality with the show is the focus on the often overlooked everyday lives of working class people.) That opportunity is one of the main reasons Gray wanted to write the cookbook, along with a previous official Downton Abbey cookbook.

“People will buy the book because they love the show, and I can sneakily get them into history,” she says. Each recipe contains an introduction that notes some history or background of the dish or its ingredients, often in addition to how it appears in the show. There are also short essays delving into things like overseas influences on cooking during a period of increasing immigration, commercial confectionery at a time of rising sugar consumption, and Christmas traditions.

The way that food can touch on so many other aspects of life is what drew Gray to specializing in the history of food in the first place, in addition to her love of both history and cooking.

“You can engage anyone through food,” she says. “It’s one of the really few fundamentals in life. We all are born. We all die. Hopefully, we all have sex—you can’t really talk about sex with children a lot. But food is this absolute universal. It tells us so much about social attitudes, it tells us so much about technology, it tells us so much about modern attitudes, because of course the study of history is very much rooted in the present.”

For example, in the case of the Call the Midwife era, the adoption of convenience foods was driven in large part by women’s increasing move into the workforce. The existence of coffee bars like the one that sometimes shows up in the show was a new development that was especially frequented by young adults and teenagers, who had left school and entered the workforce but, unlike previous generations, hadn’t necessarily married immediately and started a family.

The Call the Midwife cookbook contains recipes for numerous desserts that might go well with coffee, from the simple custard-like blancmange (try Gray’s recipe) to a sweet astoundingly called orange orgies, to rum baba. But it also includes some savory recipes that probably call up memories for certain generations in the United States as well: quiche lorraine, mulligatawny soup, chicken à la king.

Gray admits to having a soft spot for Patrick and Shelagh Turner, the (eventually) married doctor and nurse in Call the Midwife, and their time cooking such dishes together. “Just quite muted, sweet little moments: say, things like coq au vin and creamed spinach and buttered carrots and the cauliflower in mint sauce,” she says. “They’re the kind of dishes a lot of people in the UK grew up with, but you see them in their context, as something that’s brand new and really quite exciting, and it suddenly makes you go, ‘You know what, the food I had was terrible, but it was really good twenty years beforehand when it was exciting!’”

Try a recipe for blancmange from the Call the Midwife cookbook.