The Chicago Researchers Who Set Out to Solve the Mysteries of Sleep and Birthed a Discipline

Daniel Hautzinger

December 22, 2023

Do you ever wonder what happens to you while you sleep? Nathaniel Kleitman did – and set out to obsessively and objectively measure people’s physiology while they slept in order to discover the answer. As a researcher at the University of Chicago beginning in the 1920s, he deprived himself and his graduate students of sleep for up to 155 hours and tracked the effects. He attached instruments to his daughters’ cribs and beds to examine their sleep. He devised tools to measure the duration and strength of sleep movements alongside body temperature in a pre-computer age. He even spent 32 uninterrupted days living in Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave with a graduate student to try to shift their sleep cycles to a 28-hour schedule, with inconclusive results.

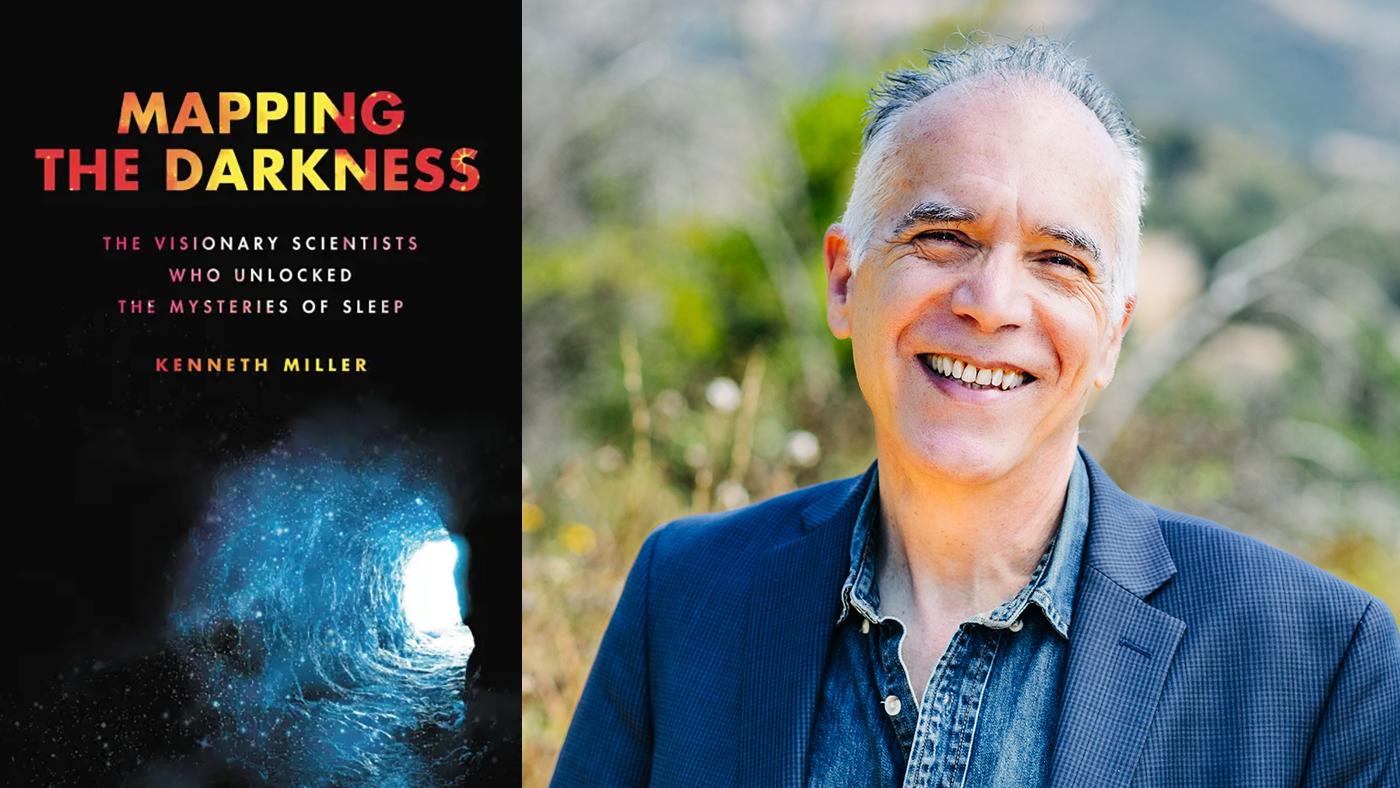

Kleitman’s time “was devoted largely to thinking about sleep, reading about sleep, writing about sleep, or conducting sleep experiments,” writes Kenneth Miller in Mapping the Darkness: The Visionary Scientists Who Unlocked the Mysteries of Sleep. Kleitman is the “father of modern sleep science,” the first researcher to devote his career to understanding sleep. He established the world’s first dedicated sleep laboratory at the University of Chicago in 1925, and wrote a foundational textbook on sleep science, Sleep and Wakefulness as Alternating Phases in the Cycle of Existence, in 1939.

While Kleitman was the only dedicated sleep researcher for nearly three decades, today, every major university hosts some sort of sleep research center, according to Miller, and there are 6,500 sleep clinics in the world. The “sleep economy” was valued at $432 billion in a 2020 study, and the World Sleep Society has 14,000 scientists and health care workers as members.

“Over the last ninety-odd years, sleep has gone from an afterthought to a central element in our notions of well-being,” Miller writes. And yet the “central mystery” of sleep – “why we can’t just stay awake” – still has not been solved. “No one can say precisely what sleep is for,” Miller writes. The story of sleep science is a detective story with no resolution.

But solving the mystery is tantalizing, and the attempt to do so has turned up plenty of fascinating findings.

“It is just so weird that we would spend a third of our lives basically unable to move or function or interact with the world in any kind of meaningful or effective way,” says Miller. He first became engrossed in the mysteries of sleep – what it’s for, why we need it, what happens to our personalities during it – after writing an article on the latest findings in sleep science, and became hooked.

It helped that his whole family was having issues with sleep at the time: he wasn’t getting enough sleep, his father fell asleep while driving. “Sooner or later, sleep troubles just touch all of us,” he says. The combination of material that interested him and his own personal connections to it led him to write Mapping the Darkness, and try to show, “How did sleep science come in from the fringe and become a global obsession?”

A large part of that story has to do with researchers who did their work in the Chicago area or were educated here. In addition to Kleitman, there was his graduate student Eugene Aserinsky, who discovered rapid eye movement (REM) sleep at the University of Chicago in 1953. William Dement worked with Aserinsky on those experiments and wrote a paper with Kleitman on the cyclical phases of sleep that is one of the most-cited scientific papers of all time, according to Miller. Dement was the first to try to treat sleep disorders and issues as a matter of health. He also organized the first American conference of sleep scientists with Kleitman’s successor at the University of Chicago, Allan Rechtschaffen, in 1961, leading to the formation of a professional organization for the science, the Association for the Psychophysiological Study of Sleep (now known as the Sleep Research Society).

Those three men, along with Mary Carskadon – who realized early school schedules were depriving teenagers of sleep – are the four main “visionary scientists” of Miller’s book. But there are other important figures in the field who also did their work in Chicago. Northwestern University’s Horace Magoun and Giuseppe Moruzzi identified a “waking center” in the brain that keeps people alert. (Rechtschaffen had a PhD from Northwestern.)

“Not only the University of Chicago, but also University of Illinois, Northwestern – all of them played an outsized role in the birth and evolution of this field,” Miller says. “It wound up being this global science, but its birth as an independent discipline really started at the University of Chicago.”

The center of sleep science shifted west in the 1960s, when Dement moved to Stanford, but Chicago continued to make contributions. Psychologist Rosalind Cartwright set up a sleep lab at the University of Illinois College of Medicine after time at the University of Chicago, and then established a sleep disorders center at Rush University Medical Center, where she was a pioneer in treating sleep apnea. She also researched dreams and their bearing on mental health. In 1999, the University of Chicago’s Eve Van Cauter made the noteworthy report that sustained sleep restriction in healthy young men led them to metabolize glucose as if they were diabetic.

“We’ve discovered a lot of incredible stuff that’s helped us develop better treatment for not only sleep disorders, but other diseases that are related to sleep,” Miller says. Research into sleep “has helped us understand what’s going on in our brains and bodies during sleep in a way that we had no idea of 100 years ago. And yet there’s so much territory that remains to be explored, so many mysteries that remain unsolved.”