Danny Solis

It’s ten o’clock on Friday morning, and 25th Ward Alderman Danny Solis is eating poached huevos rancheros with barbacoa at La Casa del Pueblo, a cafeteria in the heart of Pilsen where he holds weekly check-ins with his senior staff.

They go around the table, rattling off long lists of calls they’ve fielded over the past week. A developer is having a problem with his water permit. Residents near 18th and Paulina are requesting an honorary street for a deceased beautician. Others want their alley repaved, their sidewalk repaired, their street lamps upgraded.

This barrage of favors and projects is relentless in Chicago ward offices. But for Danny Solis, who is also chairman of the city’s zoning committee, the part of the job he loves – the thing that has inspired him to keep running for the past twenty-one years -- is the opportunity to “build up neighborhoods.”

“University Village didn’t exist before I took it over. I feel I created that,” he said. “Pilsen didn’t exist the way it does now. And talk to my critics or talk to my supporters, they all say it’s improved.”

“Of course,” he adds, “the critics will say, ‘For who?’”

After breakfast, Solis walks outside, buys a small packet of gum from a homeless vendor, and strolls down Blue Island Avenue. He passes an empty lot, several vacant and boarded-up storefronts, and an old single-room-occupancy building recently purchased by his friends at The Resurrection Project, a local, affordable housing non-profit.

“This whole street is gonna light up,” he says, explaining how he wants to build a football field just north of Benito Juarez Community Academy on a parcel of land donated by a developer in exchange for a pass on the neighborhood’s stringent affordable housing requirements, which go far beyond the city’s.

“And this will be a very nice plaza here,” he says, pointing to Fran’s Beef, a small gyros stand that’s stood on a small, triangular lot since 1995.

“It will be an area where people can walk, bike, and drive on a one-way [street],” he explained. “It will basically connect from Cermak all the way to 18th and Blue Island.”

He explains that he hopes to use tax-increment finance dollars, or TIF funds, to finance the project. It’s just the kind of thing that might roil his critics, who accuse him of making too many unilateral decisions and supporting development and zoning changes that they say are accelerating gentrification in Pilsen’s predominantly Mexican-American neighborhood.

But Solis is done having the gentrification conversation.

“I don’t think gentrification is necessarily a bad thing,” said Ald. Solis, adding that he prefers to approach it as “balanced development.”

“When you say that we want to keep a neighborhood the way it was, what do you mean? You want to keep it all working class and take the understanding that our community is not going to evolve, not going to grow? Not reach the American Dream, not go into the middle class or upper class?”

Danny Solis was born to a working class family in Monterrey, Mexico in 1949. When he was six, his mother moved him and his five siblings to Chicago to join his father, who had gone ahead of the family to find work.

Solis says his dad was a “really cool guy,” who he considered tall at 5’7". His father dropped out of school after the third grade and worked three jobs most of his life. Solis says his dad always wanted more for his own kids.

“He had a lot of common sense, and he always told me, ‘Either get yourself a union card or a college degree,’” he said.

Solis was aware from a young age that not everyone lived like his family. His best friend growing up was a boy named Phil Mullens. Phil was also an immigrant – but he was white, middle-class, and from England.

“He got a Rolex when he graduated from high school. He had the best clothes: wool, cotton,” said Solis. “His mom, because there were only three of them, she would make lamb, and they’d have steak and the proper vegetables. I first started drinking tea with milk and honey with them.”

Danny, on the other hand, started working random jobs – at an auto body shop, a flower shop, Spiegel’s, a public library, a paper company – starting at the age of 13. His favorite job lasted for only a short while: selling newspapers outside of City Hall. Not only did he enjoy the hustle of the Loop, it paid fairly well. The papers were seven cents each but “most people would give you a dime,” he said, still seemingly tickled by his good fortune.

He found ways to hustle his way through college, too, though he didn’t quite finish. He enrolled in a civil engineering technician apprenticeship to help pay for his first semester. Afterwards, he enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserves and avoided the draft. And in 1972, he enrolled in the National Teacher Corps, the predecessor to Teach for America, to help pay for his last two years.

Around the same time, his friend Phil brought him to a Black Panthers convention to “get enlightened,” Solis said. It worked.

“I meet this girl with a brown beret and boots and a miniskirt, and I fall in love,” he said, laughing. “After that, I was into being an activist and becoming a radical.”

He became a member of Students for a Democratic Society and became actively involved in the push for more Latino representation at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). He got arrested for occupying a university building along with recently pardoned Puerto Rican nationalist Oscar Romero Lopez.

Then, soon after dropping out of UIC, he co-founded and directed the Latino Youth Alternative High School in Pilsen. He enlisted help from his college friends – mostly progressive academics and lefty artists – to get kids who were using drugs interested in learning.

In the early 1970s, Pilsen became Chicago’s first proudly and predominantly Mexican-American neighborhood, and there was a lively activist scene. Solis was involved on several levels. He got hired to be the first Latino director of Pilsen Neighbors Community Council, a grassroots effort to improve housing, build educational opportunities, and organize residents. He served on the board of the newly formed Eighteenth Street Development Corporation, which worked to create job opportunities for young people. And eventually, he co-founded the United Neighborhood Organization, or UNO, whose goal in those early days was to build political power in Chicago’s growing Hispanic community.

As part of UNO, Solis attended intensive training with Industrial Areas Foundation, the organization created by community organizing pioneer Saul Alinsky. He says the experience was transformational.

“It improved my organizing skills but also made me understand a difference between the public and private arena, understand power better, understand self-interest,” he said.

With this strategic approach, Solis steered UNO towards school reform – specifically, a campaign to create local school councils in Chicago public schools. He said he was able to get his colleagues at UNO on board because there was money in it: corporate donors were willing to ante up. Solis, meanwhile, saw the campaign’s potential for building the political muscle of disenfranchised Latino communities.

“We were numbers, but we were powerless,” he explains. “We couldn’t vote. Most of us were non-English speaking, we were intimidated by authority. This was something where, hey, you can run, you can be elected. You didn’t have to be a citizen, didn’t have to speak English, you didn’t have to be legal. You just had to be a parent or be in the community.”

It took time but eventually they won. The Chicago School Reform Act of 1988 established local school councils, or LSCs, at every Chicago public school. Riding on the heels of that victory, UNO set up phone banks and encouraged widespread participation in the 1990 U.S. Census, a process that would later help determine the configuration of city wards and state congressional districts. From there, the organization launched a massive naturalization campaign in 1992, eventually helping thousands of Latino immigrants in Chicago gain U.S. citizenship and the right to vote.

Meanwhile, in City Hall, the newly elected Mayor Richard M. Daley was looking for ways to connect with the city’s growing Latino electorate, whose support he understood would be key to his political future. Daley started consulting Solis and, eventually, testing his political mettle. In 1992, he appointed Solis to the Chicago Housing Authority Board of Commissioners. In 1995, he appointed him to the Regional Transportation Authority board. During this time, Daley’s brother, William, also recommended Solis for Fannie Mae's National Advisory Board, a position which also helped UNO secure lucrative grants from the company’s foundation.

Then, after 25th Ward Ald. Ambrosio Medrano was ousted in 1996 for taking $31,000 in bribes and pleading guilty to corruption, Daley appointed Solis to fill his seat.

He immediately got on board with several Daley initiatives, chief among them a public-private partnership between the city and UIC to build University Village, a large-scale development that includes dorms, townhomes, condos, and retail development along Halsted Street.

The University Village project would eventually be subsidized with $75 million in TIF, or tax increment financing, dollars, providing the new alderman with a crash course on how to leverage city subsidies in support of private business and development. Chicago’s controversial TIF program diverts a portion of property taxes within any given area away from the general fund and towards an account that can then be used to subsidize development. It has come under criticism for lacking transparency or any public process and for siphoning millions of dollars from citywide operational expenses, pension payments, and public schools.

An outpouring of community opposition to University Village laid bare a key ideological schism between Solis and many of his longtime allies, including Teresa Fraga, who had also held leadership roles at Pilsen Neighbors and UNO and who believed that the project would accelerate gentrification and the displacement of low-income residents.

The issue was front and center during the special election to replace Medrano, in which Fraga and two other candidates ran against Solis. One of them was former Ald. Juan Soliz, who accused Solis of wanting to “sell out Hispanic people” and create a “yuppie paradise close to the Loop” in a 1997 column by the Chicago Tribune’s John Kass.

But Solis dug in his heels, rejecting his opponents’ narrative. “Our people traveled great distances to come here, through many hardships," he told the Tribune. “And now there is a chance to have a Mexican neighborhood we can point to as successful, with Hispanic professionals and working people and families living together.”

In February 1997, he won 77 percent of the vote. And he never looked back.

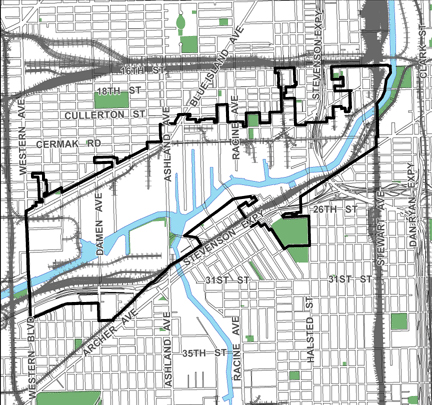

Pilsen Industrial Corridor TIF. Photo courtesy of city of Chicago

In those first three years, City Hall created four new TIF districts in the 25th Ward, chief among them the 907-acre Pilsen Industrial Corridor TIF. Since that time, according to City Clerk records, the Pilsen TIF has raked in more than $147 million for local development projects.

While much of those funds have gone to private businesses (including $9 million to build a new International Produce Market at 2431 S. Wolcott Avenue in 2001 and $5.3 million for the Target at Damen and 31st Street in 2005), the Pilsen TIF has also helped pay for job training ($1.3 million since 2001), athletic fields at several local schools, and multiple street repaving, bridge repair, and green infrastructure projects.

“It’s really paid off,” said Solis, who added that the TIF funds are sometimes eight times greater than the amount he gets for his “menu” items from the city, slated for regular infrastructure repairs in the ward. “I can use TIF to really augment [funding for] sewers, lighting, alleys,” he said. “It really enhances the neighborhood.”

But critics argue that the way that TIF money is spent doesn’t necessarily reflect the wishes or needs of the local community. Among them is Raul Raymundo, who has known Solis and worked closely with him for years as CEO of The Resurrection Project, a non-profit development organization that, with Solis’s support, has created more than four hundred affordable units in Pilsen during his tenure and pressured developers to include double the citywide mandated units in any large-scale projects. While the two are allies on several fronts, Raymundo isn’t without criticism of Solis.

“He rushes through things too fast…without getting that support behind him,” said Raymundo. “He often says ‘I, I, I’ rather than ‘we, we, we.’”

Solis is aware of the criticism. “My argument to people is: look, you elected me to get some stuff done, and I’m gonna get it done. If I don’t get it done or if you don’t like the way I did it, you can get me out. But I can’t be meeting every second.”

Solis sees the fact that he continues to win elections – though occasionally by a narrow margin – as a testament to his constituents’ overall support for his approach.

“One thing I think even my critics can’t [argue with] is that all of my neighborhoods have improved. Now they might not like the improvements because they say ‘gentrification’ [quotes by Solis] is pushing people out. But they can’t deny they’ve gotten better. The neighborhood is safer. The schools are better. Crime is down. Property values are up,” he said.

Indeed, the murder rate has been consistently lower since the late ‘90s. And no one disagrees that property values have gone through the roof.

But his critics, including lifelong resident Vicky Romero, say the progress Solis touts is oversold and doesn’t benefit all of his constituents equally.

“We still have gang issues. We still have drug issues. Young Latino kids are still killing themselves in the neighborhood,” said Romero, who is a former board member of anti-gentrification organization Pilsen Alliance.

Census data support her assertion and show the median income among Latinos has declined in Pilsen (or the Lower West Side) between 2000 and 2013, from $35,989 to $32,126 annually. Meanwhile, the median income among Pilsen’s growing white population is significantly higher.

White and Hispanic Pilsen Median Household Income by Year

White and Hispanic Pilsen Population by Year

Data sources: Population data is from the U.S. Census Bureau. Population figures for 2000 and 2010 were compiled through the decennial census, while 2005 and 2015 data are estimates based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. Median income by race is taken from University of Illinois Chicago professor John J. Betancur and Youngjun Kim’s 2016 study, “The Trajectory and Impact of Ongoing Gentrification in Pilsen.”

In addition, says Romero, “If I’m not planning on selling, I don’t want my property value to go up. All that means is that I’m paying higher taxes and that people who can’t afford those taxes are being pushed out of my neighborhood. Improving a neighborhood shouldn’t come at the cost of displacing people.”

Solis rejects the characterization.

“If you really look at it, it’s not that we [Mexican-Americans] are being pushed out,” he said. “People are saying, ‘Hey, I’m going to cash out,’ which is good for them.”

He points out that demographic changes taking place in Pilsen are part of a citywide shift that is most pronounced in the central district, where Mayor Rahm Emanuel has used massive tax breaks and subsidies to attract tech companies and corporate headquarters.

“Our city is changing, and I'm on board with that vision,” he said.

Although Solis wasn’t initially supportive of Emanuel’s bid for mayor, he has changed his tune since Emanuel’s election. A recent UIC analysis found 100 percent of Solis’s votes between 2015 and 2017 in lockstep with the mayor’s agenda.

“Me helping the mayor helps me out. I haven’t been here 21 years without understanding that,” explained Solis.

“And I think in order to help my constituency – and I see my constituency as not just Hispanic but primarily Hispanic…we've got to focus on them being connected to that future vision for the city.”

Asked how low-income residents, in particular, might find a place in Emanuel’s future Chicago, Solis pointed to efforts to create and preserve local jobs and improve educational opportunities.

On the job front, he continues offering financial support and grants and has recently begun working to create a Pilsen chamber of commerce.

On the education front, he’s working with the organization he used to run – Pilsen Neighbors Community Council – to organize local public school principals and create a coordinated plan that identifies and builds upon the strengths and specializations of each. Jungman Elementary School, for example, is on its way becoming a magnet STEM school. Orozco Elementary Fine Arts & Sciences, which caters to Spanish-speaking students, houses a bilingual, regional, gifted center. And Benito Juarez Community Academy has recently launched its own International Baccalaureate and career and technical education programs.

“The key is that we have a good education system that gets kids from all different strata,” he said. “That’s the equalizer.”

He said that having a good education will be crucial in Chicago’s future economy.

“The mayor is creating a city that's going to be like Seattle,” he said. “Millennials will rule. And you're going to have an uptick of the well-educated, tech-savvy millennials, especially in the central area. And I think, overall, I think that's good. I mean, you have to remember, my kids are millennials.”

Solis has gained some of that central area during the 2015 redrawing of ward maps. The 25th Ward lost some of East Pilsen and the Medical District but stretched north, encompassing more of University Village and the Near West Side before extending like a swollen elephant’s trunk down and along the Chicago River through much of the South Loop. The new map also gave Solis several new TIF districts, including the lucrative River South TIF.

The new map has also given him new neighborhoods that he’s excited to redevelop.

“My next big project is the South Loop, by the river. That’s gonna be tremendous. That whole river [from the] post office down to Chinatown – that is, wow,” he said, trailing off. “But that’s at least a ten-year project.”