The Chicagoan Credited with Popularizing Caramels in America

Meredith Francis

October 19, 2023

Chicago Stories: Candy Capital premieres on Friday, October 27 at 8:00 pm on WTTW and streaming on the PBS app and wttw.com/chicagostories

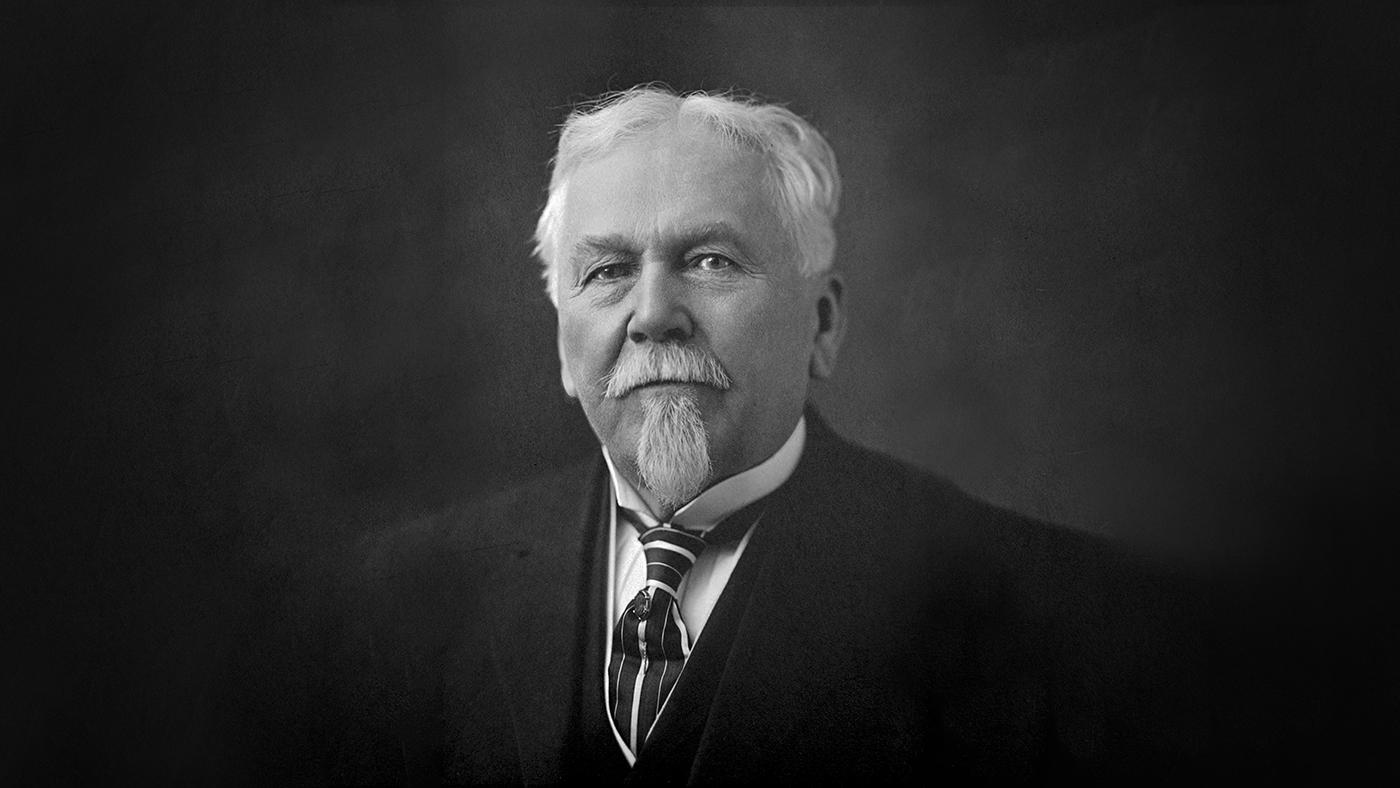

Caramels have long been a staple in the confectionary world, and for that you can partially thank Charles F. Gunther – a man with the eclectic description of candymaker, Chicago alderman, and avid collector.

“Caramels were not invented in Chicago, but Gunther is often credited with the mass popularity of caramels in the 19th century,” Leslie Goddard, author of Chicago's Sweet Candy History, says in Chicago Stories: Candy Capital.

Born in Germany in 1837, Gunther settled in the United States with his family as a child and held several jobs as a young man. During the Civil War, he worked for the Confederate Navy and was captured and held by the Union Army for some time.

After the war, he traveled to Europe, where he learned about caramels and candy making. In 1868, he opened his own candy shop on Clark Street in Chicago, but his first shop was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire in 1871. He then opened a larger factory and shop on State Street, and business boomed as wealthy Chicagoans like Bertha Palmer supported his business.

Color illustration depicting Gunther's Store and Soda Fountain located at 212 State Street, Chicago, Illinois, circa 1887. Credit: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-021804

Color illustration depicting Gunther's Store and Soda Fountain located at 212 State Street, Chicago, Illinois, circa 1887. Credit: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-021804

Gunther found so much financial success in the candy business that he was able to use some of his fortune to purchase expensive artifacts, particularly from the Civil War. He was quite the collector.

“He bought a prison from the Civil War and shipped it to Chicago,” Goddard says in the documentary. “It laid the foundation for Chicago to be home to one of the greatest collections of Civil War artifacts.”

Gunther’s collection also included the bed on which Abraham Lincoln died, the table where Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, and George Washington’s compass.

Gunther also served as a Chicago alderman for the Second Ward from 1896 to 1900, and he served one term as the city’s treasurer. He died in 1920 and was buried in Rosehill Cemetery. Upon his death, the Chicago Historical Society purchased his artifacts, paintings, and manuscripts. With its growing collection, the Chicago Historical Society built a museum at Clark Street and North Avenue to house its expanding collection, which had been mostly destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire. Today, the Chicago History Museum still houses some of his collection.