Farm-to-Mug

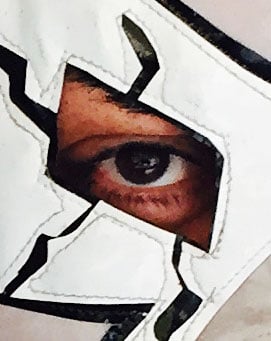

Mike Pilkington at Bridgeport Coffee

Bridgeport Coffee’s Mike Pilkington started buying his beans from some guy in Colorado. Now he’s building relationships with coffee farmers in El Salvador, and around the world.

Mike Pilkington and two friends opened Bridgeport Coffee in 2004, just as coffee’s “third wave” was taking off. This coffee renaissance – which emphasized direct trading with coffee farmers, lighter roasting, and new brewing methods like the pour-over – coincided with Bridgeport’s own resurgence. The shop’s South Side neighborhood is “a different place entirely than it was 10 years ago,” Pilkington says, noting the new shops, restaurants, and a developing community of artists in the area.

Bridgeport Coffee opened at a time when there weren’t many local roasters.

“There wasn’t a lot to choose from in those days, so we decided to buy a… one-pound roaster,” he recalls. “We vented out the basement window at the coffee shop, and I roasted all the coffee that we served at the shop, one pound at a time.”

A new shipment of coffee, at Bridgeport Coffee's roastery

A new shipment of coffee, at Bridgeport Coffee's roastery

It wasn’t long before Bridgeport Coffee attracted the attention of Chicago restaurateurs, and in 2005 they upgraded to a much larger roaster. “Now it’s nine years later and we have 120 wholesale customers and three coffee shops. We’re going to roast 110,000 pounds this year,” Pilkington says.

Bridgeport Coffee initially sourced green coffee beans from “some guy in Colorado” and a Peruvian importer, but in 2005, they started buying directly from farmers around the world. Now Pilkington visits Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and El Salvador to buy the beans himself, from farmers like Ernesto and Fernando Lima of El Salvador. Pilkington met the brothers when Ernesto’s niece visited his Bridgeport shop, and what started as a small purchase through an importer in 2007 has turned into a long-term relationship with the Lima family.

“When they come here, we go to dinner,” Pilkington says. “When I go there, I go to their home. It’s not just a directly traded coffee; it’s a true relationship coffee.”

When selecting coffee, Pilkington looks for the right body, flavor, balance, and acidity; but he also wants to make sure that his coffee remains accessible to a broad audience. He describes a coffee from the Lima brothers’ farm as “sweet, well-balanced, medium-bodied,” but also adds, “If you had a bunch of coffee geeks sitting around a table they would love this coffee, but grandma, she would like it in the morning, too… It’s a great restaurant coffee because it has really wide appeal.”

He also aims to keep the descriptions of his coffee accessible.

“Sometimes we use terms like sweet citrus or lemon, but for us, it’s about using terms that people who are buying the coffee can understand,” he says. “When we start using terminology like stone fruit and these kinds of obscure flavors, we’re not really telling the people who are buying the coffee anything. I don’t even know what stone fruit tastes like.”

But Pilkington ultimately likes to give all of the credit to the coffee farmers like Ernesto and Fernando Lima. When roasting the beans he simply wants to make sure that he doesn’t “mess it up.”

“There’s nothing that we’re trying to change in this coffee,” Pilkington says. “Fernando is the one who made this coffee. We roast it, we help tell the story, and we are tasked to care for it.”